I spent 40 years in intelligence analysis, working within the confines of standard operating procedures both intellectual and bureaucratic, while also engaging in continual sidebars with colleagues as skeptical as I of the anomalies in our rationalist paradigm. The central norm of our business is to filter out personal opinions and biases in favor of objective assessments of events and trends affecting national security. As we sifted through evidence that sometimes is contradictory and always is incomplete, we pruned out adjectival hot buttons to focus on evidence, logic, probabilities, historical analogies—always imperfect—and analyses of alternative judgments and futures.

I still believe this approach has a lot going for it. It enables analysts to sharpen their judgments in cooperation with colleagues who have disparate and even conflicting backgrounds, instincts, religious beliefs, and political views. We take it as a point of pride that we can produce collective finished intelligence in support of policy makers of any political or ideological stripe.

These conventional approaches to conceiving and producing competent, useful research and intelligence, however, are increasingly at odds with the world being analyzed. Neither intelligence analysis nor the banal statistical grind of contemporary political science is equipped to address the growing challenges to our understanding of—and more importantly, our feeling for—the ways human beings compete for power and influence.

Norms and rules were once supposed to organize the competitive process in Western politics, but that assumption is no longer viable in in the United States, and the result of the 2020 election is not going to change that.

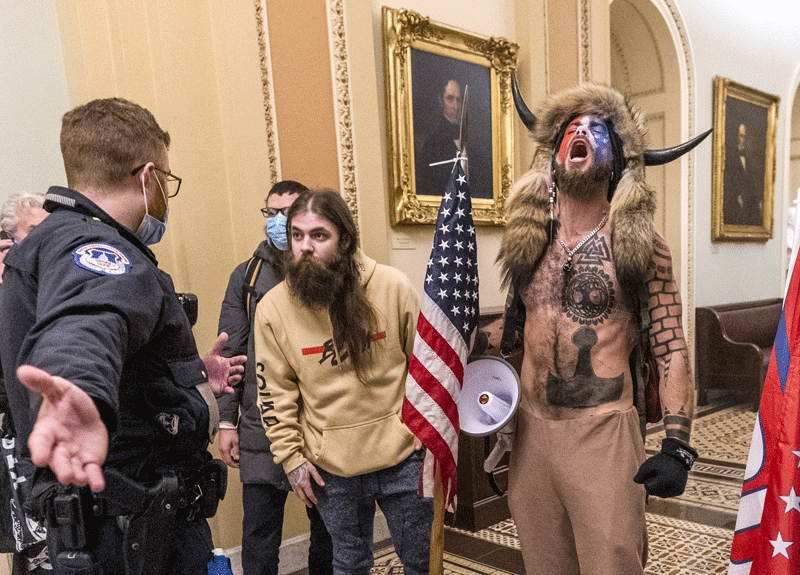

The conspiracy theories and hero-and-villain social caricatures bedeviling our current politics are symptomatic of a larger collective sense of disorientation, anxiety, and fear that there exists no clear, safe way forward in a post-modern world, and this malaise undermines the value of the painstakingly analytical process we used to rely on.. The widespread uneasiness—both personal and institutional—is due not simply to the recent and, let’s all hope, temporary unraveling of our government and society, but also to the snowballing structural and technological changes that will to continue to shift the social ground under our feet.

AP/Manuel Balce Ceneta

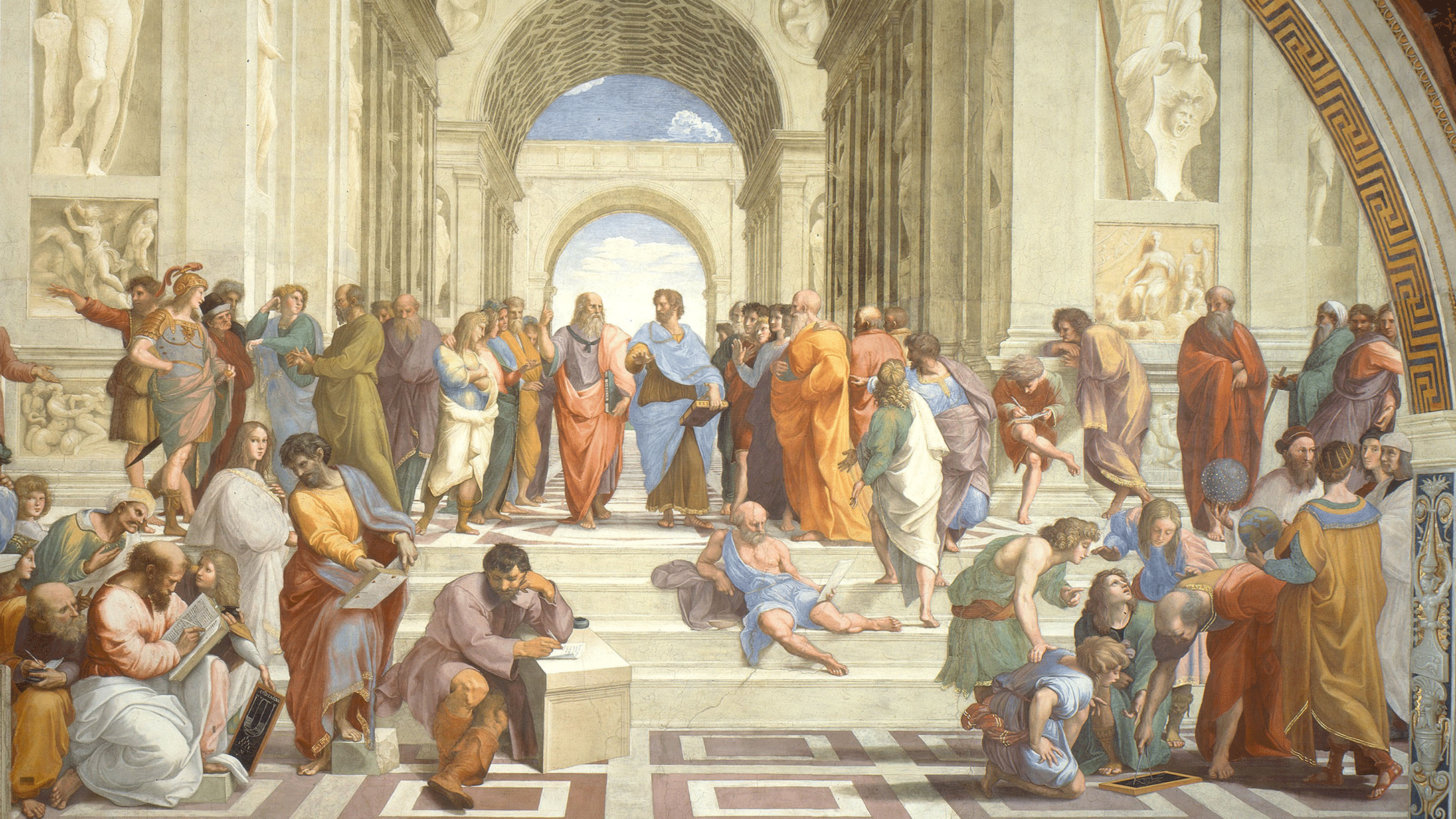

AP/Manuel Balce CenetaThere’s a real disconnect between formal assessment and the emotional motivations and content of so many actions by non-state and sometimes even state actors. We are facing a contemporary version of periodic changes in the relationship among the three corners of the ancient Greek trivium – grammar, rhetoric, and logic. In the mid-15th century, for example, a tech innovation, the printing press, kickstarted the rise of logic—written and disseminated from a long distances (temporal and spatial, and increasingly, across class lines)—over persuasive rhetoric, which had been communicated face to face and largely between elites, in the Socratic model.

The instantaneous exchange of information and, more importantly, persuasive truths and untruths flooding social media, are reversing this relationship—except now, rhetoric-driven emotions can reach all classes and communities in real time. To remain useful, analysts and pundits will have to become willing to question comfortable worldviews, and fight the instinct, which has so often proved dangerously wrong, to demonstrate their Olympian ability to explain things via comfortable rationalization.

Who succeeds in choosing the words we use, and whether those words are communicated orally or in writing, lays the groundwork for changes—sometimes even drastic changes—in social organization. The Brothers Grimm did not just record fairy tales; they compiled dictionaries, which served as weapons in competitions throughout central and eastern Europe to determine which dialects (and speakers) would dominate emerging “national” languages. Using standardized tongues, political entrepreneurs have succeeded in defining the terms of self-celebration and marginalizing challenges to iconic communal imagery.

In a similar way, traditional and social media have morphed concepts into popularized slogans that enable inertia, complacency, and work avoidance. We continue to hear politicians and pundits invoke something called “the international community,” shorthand for a fading Western-dominated order. When someone refers to “’the’ _______ people” (fill in the blank with a country name), it is wise to question the extent to which such a civic identity exists. Calls for unity and national healing are a dime a dozen, and everyone everywhere rails against “corruption”—even as individuals and institutions exploit their own “connections” whenever they are useful.

Western political institutions are grounded in such formulations as “democracy,” ”rule of law,” “transparency,” and something called “good governance.” Such concepts undergird the notions of trust on which the Western system relies: Individuals, companies, and communities can trust these rhetorical structures to create a level playing field permitting them to work and strike deals with people whom they do not trust. If a transaction works out poorly for you this time, you can be confident you will have a fair chance to do better the next time.

The rise of instantaneous audiovisual communication is exploding confidence in that long-held understanding. Deals are made and unmade, conspiracy theories morph and metastasize, and laws are broken or evaded faster and and in volumes too overwhelming for our clunky constitutional institutions to handle. The future of print-mediated bureaucracies is in question, no matter how many computers they now host. The rhetorical power unleashed by increasingly personalized, improvised, tweeted and insta-whatevered assertions and insults is undermining purposeful dispassion on a global scale, reducing every issue of allegiance and abhorrence to the single question: “Who, or what, do you trust?”

This new force of family, tribal, and patronage-based networks reverses the print-era balance between logic and rhetoric in the political arena. Legal systems and inertial bureaucracies are being inundated, or sidestepped, or coopted by informality. The development of digital currencies may seem marginal now, but it is likely to become a major enabler of informality—even outright crime—and a growing challenge to traditional sovereignty. Going forward, there may be far less need for informal actors to steal or counterfeit the means of conducting material transactions and accumulating wealth.

In short, those currently conducting intelligence analysis are going to have to improve at assessing and communicating the impact of collective, armed emotions on geopolitical tectonics.

If I were kicking this around at CIA, by this time my colleagues would have interrupted me with insights, objections, and creative, useful non-sequiturs. When I was a part of the Agency’s Red Cell, a small group devoted to the analysis of alternatives to mainstream analytic judgments, the product of a discussion like this would have been devoted to “what if,” devil’s advocacy, or a compare-and-contrast exercise involving history and trend analysis. Since leaving government I have had the opportunity to take part in academic discussions and post a few opinion pieces related to stuff I once worked on. Nevertheless—speaking of trust—I miss the mutual respect and careful exclusion of personal judgment involved in the thrust and tussle among intelligence analysts, no matter my misgivings about my former profession’s trajectory.