My problem is that I can’t. Because every time I put on a dress, or lingerie, or anything coded as feminine, all it does is flip the very un-nuanced switch in peoples’ heads from the “boy” delineation to the “girl” one. I’ve never been able to wear a dress in a masculine way, which sucks, because it’s all I’ve ever really wanted. And because I love dresses.

When you’re trans, people make comments about your body and the assumed bravery that goes along with it, quite often. They assume you’re brave because they can’t see themselves doing what you do. Trying to live as a type of illusion – a girl trying to be a guy trying to look like a girl. But it’s not an illusion to you. It’s a manifestation.

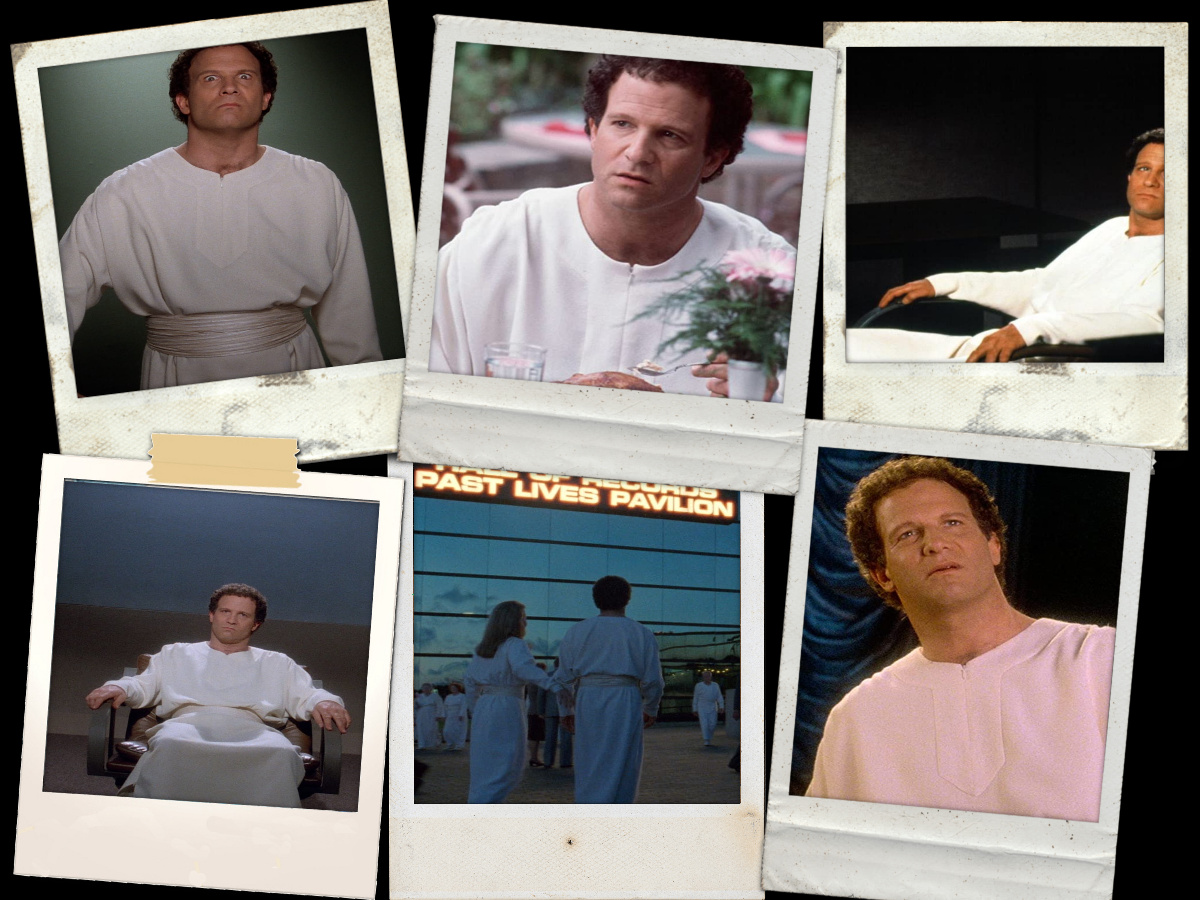

In Defending Your Life, Albert Brooks wears a series of white, flowing garments. The first is an update on the classic hospital johnny, a basic white cotton t-shirt dress with pockets. It’s the perfect genderless outfit: there’s enough billow and flow to create a suggestion about the body underneath, yet it moves with Brooks’ body, constantly enfolding him in a shifting, cloudy aura.

****

I’ve always been jealous of men who can pull off a dress. I’ve been jealous of priests, with their black, high-necked cassocks, and saints with their beautiful gilt-edged robes. On occasion, I’ve been jealous of Jesus himself, because it’s actually rude of a cis man to look so goddamn good in an empire waist dress.

Wishing I looked as good as a man in a dress is an ancient feeling for me.

Whenever I watched movies set in Ancient Rome and being upset that the centurions were basically wearing miniskirts. I loved the way Danny Kaye looked in tights and a doublet in “The Court Jester.” I loved the way Phil Silvers and Zero Mostel looked in “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.” Franco Nero in Camelot, wearing tights that emphasized his bulge. Even Danny Kaye and Bing Crosby when they wear the Haynes Sisters’ costumes in “White Christmas”: ostrich feather boa, sparkly butterfly barette and all. Because they all, to me, looked beautiful. And like they were free from something. Something important.

I couldn’t be free of it, whatever it was. I knew that. Still, I tried to make man-dresses happen. I loved wearing tights and dresses for the way they made me feel in private, and I hated wearing tights and dresses for the way they made people look at me. I wished I could offer them some context. “It’s not really what you think,” I wanted to say. “I’m basically a trans woman trapped in a trans man’s body.”

But I doubt that would ever have clarified things.

I remember feeling this way at Prom, where I decided at the last minute, after all my friends had bailed on our more creative plans for the evening, to wear a Jean Harlow silk slip with white, elbow-length gloves. I tried it on beforehand, thinking I was alone, and my mom saw me. “You look like a princess!” she cried. She was so happy that I looked like a princess. There was no getting out of it. I ended up having a small breakdown at prom, wandering down to the weird offices of the log cabin event space where it was held, where an employee found me and placed me on suicide watch for the rest of the evening. That night, as everyone grinded to SOS on the dance floor, I could see the watching, worried eyes of employees wherever I went.

There’s no hiding when you’re in a dress. And that can be beautiful, sometimes. It’s never been beautiful for me.

The problem is that I can’t accept that I’ll never be able to subvert a dress. The minute it touches my body, we become “girl.” It doesn’t matter what I want.

But I can love how beautiful other men look. I can get pleasure from seeing the way it softens Albert Brooks in this movie. The tupa is an outfit, but it’s also a symbol. You’re free from the bullshit of earth when you die, and clothes are a big part of that bullshit.

*****

Defending Your Life is known for many things, but fashion isn’t necessarily one of them. It’s a beloved film that manages to be both playful and grim about a potential afterlife, and it leaves religion almost entirely out of it. It’s got a perfect cast, with bravura performances from Rip Torn, Lee Grant, love interest Meryl Streep, and Brooks himself. And it’s a movie that I now return to over and over, when I’m feeling just about anything I don’t want to feel.

I saw all the Albert Brooks movies this summer, along with a lot of us on Twitter. They were on the Criterion Channel, and it felt like this beautiful moment where suddenly everyone was remembering how wonderful his body of work truly is – but Defending Your Life is special. Its notion of death feels both very Jewish and very gay. In other words, very me.

When the film starts, Brooks is Daniel Miller, an ad exec celebrating his birthday. He buys himself a new convertible and blasts Barbra Streisand, until he’s hit by an oncoming bus. When we next see him, he’s in that cotton shift, looking dazed and sacrificial. After those few scenes, he’ll wear the same outfit, called a “tupa” by the people in charge. We learn very little about this “tupa,” except that they “fit everybody” and that’s probably why they’ve been chosen.

They’re also just beautiful garments. The tupa is a classic gown with a flowing kaftan quality, but the several fine touches elevate it. The front panel detailing is wonderfully subtle, hiding a zipper that acts as the only really customizable element. The bottom hem has zippers as well, on both sides, giving the effect of a saucy side-slit during the tracking shots. The sleeves are ever so slightly ruched at the top and tapered at the bottom, creating a kind of inward crescent from armpit to waist. The effect, on Brooks, is to both round out his shoulders and bring them slightly forward. There’s a lovely belt/truss detail that gives it shape and keeps it from looking like the white bag of the first dress. The tupa ends (begins?) in a high scoop-neck, isolating the neck and crown of curls above and giving Brooks the look of a living bust. Rip Torn tells him that the tupa is flattering on him, and he’s goddamn right. The way Brooks looks in that dress is the way I’ve always wanted to look. Both masculine and gentle, vulnerable and strong.

It’s notable that Brooks’ character is on trial not for any bad deeds, but for his failures of masculinity. For each of his 9 trial days, Daniel must watch his failures on earth, most of them having to do with all the ways in which he failed to be a traditional Western dude-bro. Examples include: that time he didn’t fight back on the playground, the time he made a bad investment (cattle!), the time he didn’t ask for more money at his job. He even gets called out for not fucking Meryl Streep when given the chance. The female prosecutor (Lee Grant) is dead-set on showing how Daniel didn’t live up to our culture’s expectations for men, many of which revolve around money. Rip Torn, the male defense lawyer, is making the case throughout for Daniel’s vulnerability as strength.

The dress, somehow, helps with this. Without the dress, we wouldn’t have that visual shorthand of looking at his body in flowing robes and seeing him as something removed from the constraints of masculinity. We wouldn’t be able to look at him the same way. The dress is a facet of the vulnerability that Rip Torn is arguing for. It lets us see that the idea we have of what a man is is so often defined by the superficial: clothes, sex, money, power. Without all those things, what does a man become?

As far as I can tell, the answer is: beautiful.