In the summer of 2019 some friends and I made a trip to Rashayya. We had always wanted to visit the national monument widely known in Lebanon as the Citadel of Independence, or Rashayya Citadel.

The Rashayya Citadel was built by wealthy landowners in the 18th century, when the Ottoman Empire controlled the region. In 1920, during the French Mandates, it became a colonial military installation, and so it remained until independence in November 1943.

Lebanese history textbooks tell the story something like this: The new parliament elected Bechara el-Khoury as president; he instructed parliament to write French rule out of the constitution. The French went apoplectic, arrested the independence leaders Khoury, Solh, and four others, and locked them up in Rashayya. Then protestors flooded the streets, clashing with French troops and ultimately forcing De Gaulle’s hand. When the prisoners were released on November 22nd, 1943, Lebanon had gained its independence. That’s the official narrative.

The unofficial story, supported by documents from various colonial archives, reveals that it wasn’t until Winston Churchill—who loathed De Gaulle—threatened to expel all the Free French troops from Lebanon that the French backed down.

In any case, we wanted to visit a site perpetually heralded over years of schooling.

The road to Rashayya from Beirut is long and hilly. First you drive up Mt. Lebanon on the Beirut-Damascus road until you reach the town of Dahr el-Baydar. You’ll pass through an Internal Security Forces checkpoint, where derelict grey barracks and old US army trucks equipped with snowplows are clustered on either side of the road. Then you descend, on a stretch of highway that’s been under construction for as long as I can remember. The Beqaa valley at the base unwinds slowly, then stretches gloriously forth. The plain is dotted by an array of plots—green vegetation, red soil and golden wheat in an irregular collage. From a distance in the scorching August sun, it’s like a glistening Monet landscape come to life.

Your first stop will be at Chtoura, a buzzing hive of transit, where the air is thick with exhaust fumes and the shops mostly sell either hunting gear or dairy products. When you return to the main road, you arrive at a fork: left to Baalbek and Roman ruins, or right to Rashayya and the Lebanese South. Then there’s a 50-minute stretch of mostly steady plains. The red valley between the two steep mountain ranges that define the rugged topography of Lebanon grows narrower with every village you pass. A couple of miles on, you’ll make a sharp left turn at the small hamlet of Aaqbeh, and drive east toward the Syrian border. Ten minutes later, you’ll finally reach Rashayya.

The quiet old-fashionedness of the place was striking, and it would have been easy to mistake the local convenience store for a mini museum of 1950s consumables. The palace citadel sat atop the town, its roof adorned with the characteristic red tile, imported from Marseille, that would one day come to define the Lebanese national image.

An old woman, short, dressed in all black, her grey hair tightly tied in a knot, greeted us at the top of the steps. Proudly presenting herself as the keeper of the citadel, she held a giant keychain, ready to lead the way. She told us how stones mined from local quarries adorn all the walls of the citadel, keeping the rooms cool. Upstairs, a small key unlocked giant timber doors; they swung wide into the main exhibition hall, where the story of independence would be told.

It was a sparse, archaic exhibition. Large bulletin boards with wooden frames stood in adjacent rows, bearing newspaper clippings and historical photographs of Khoury, Solh, and their co-conspirators, and of men standing on the parliament steps, smiling for the camera. In other photographs, French troops in grey uniforms faced crowds carrying banners demanding the release of the Lebanese leaders. There was a glorious photo of the flamboyant Emir Majid Arslan, one of Khoury’s cabinet members, with his distinctive curved mustache; he had managed to evade French authorities. The head of a powerful Druze family, he’d set up an independent government up in the hills of Mount Lebanon during the independence crisis, daring Catroux to come arrest him.

Another exhibit displayed the things Khoury had been allowed to bring with him to prison: trousers, shaving equipment, papers, pens. The cell opposite him belonged to Riad el-Solh. Our guide eagerly emphasized how the French had separated the president from the prime minister to prevent them from devising any more sinister plans. Riad el-Solh’s room was smaller and dimly lit. Even in a miniature carceral schema like this one, the French couldn’t help but act on their sectarian preferences and their incessant need to segregate Lebanese of different sects from one another. The Christian president’s room was large and well it, while the Muslim prime minister received a significantly less comfortable arrangement.

There was a casual, makeshift souvenir shop offering nationalist trinkets—coffee mugs and bronze keychains (“Made in China” and depicting the Lebanese flag) were for sale alongside locally produced strawberry and fig jams.

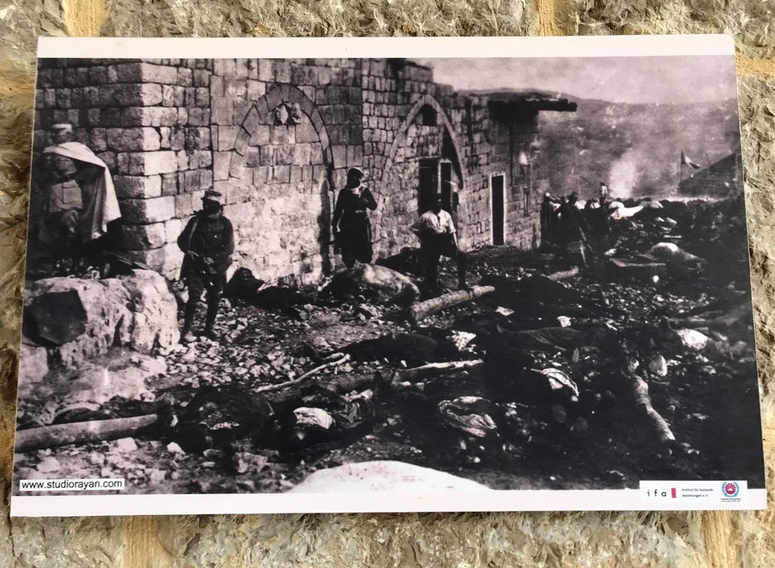

In the corridor connecting the large doors to the main hall, we found black and white photos depicting scenes of battle: Soldiers standing near an artillery gun (from their uniforms I assumed they were French), and images of bodies strewn across the ground, with ruined houses in the background. I asked the guide to explain the photos and she sharply replied, “hol taba’ el-majzara el fransawiye” [they’re about the French massacre]. At first I wasn’t sure which massacre she meant, and then I stepped into one of the main rooms, which was styled like an old bedouin tent. Pillows lined the floor and the walls were crowded with pictures, captioned this time. “Sultan Pasha al-Atrash” I read below one portrait, and finally things clicked into place. The pictures in the corridor and in this room commemorated the events of the Great Syrian Revolt of 1925, and the town’s pivotal role in the uprising.

Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, a local leader from the Jabal el-Druze in southern Syria, launched an uprising against the French in the summer of 1925. By November, the rebels had reached the town of Rashayya, where a mix of Christian and Druze residents lived. The small French garrison at the fort was surrounded by the rebels, most of whom had traveled from nearby Wadi el-Tayim through Mt. Hermon; they were joined by some, predominantly Druze, residents of the town. French reinforcements were ordered in from Beirut, armed with heavy artillery, to put an end to the rebellion. They killed some 400 men, and later punished the residents of Rashayya who had participated in the uprising.

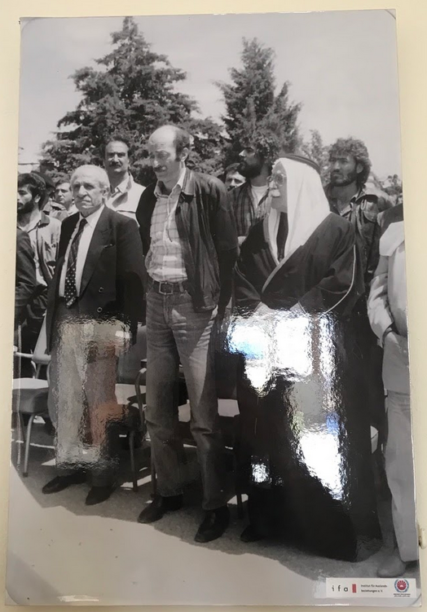

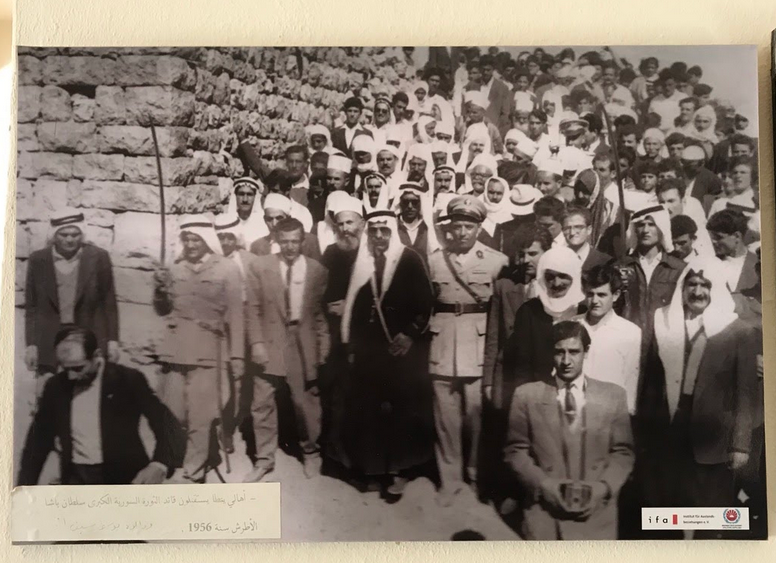

The corridors of the Lebanese Citadel of Independence were a double monument, commemorating the anti-colonial uprising of neighboring Syrians and fellow Lebanese who refused either to acquiesce to French designs or to acknowledge the newly established borders separating the two states. There was even a sort of shrine in one room to the leader of the revolt, Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, with pictures of him holding a rifle on horseback, and revisiting Rashayya some forty years later at the town-held anniversary of the uprising. Here, he stood in his Arab thawb, a brown headscarf circling his aging face, donning his trademark aviators, with the Druze leader Walid Jumblatt beside him.

Suddenly it dawned on me that in this rather mediocre palace various historical narratives were in mutual conflict, intertwined both in the physical space of the exhibition and in the person of our guide. She seemed proud to explain and elaborate on every display. The citadel of Rashayya, as well as its keepers, celebrated both countries’ conflicting historical narratives, all tied to this patch of now-uncontested Lebanese territory.

The borders of the current Lebanese state were set by Henri Gouraud, the first French High Commissioner to the Levant in 1920, in order to support and sustain their minority Christian allies in the region. Gouraud joined the Bekaa valley, Tripoli and its hinterland to the north, with Sidon, Tyre and their surroundings in the south to Mount Lebanon and Beirut, establishing the state of Greater Lebanon. Rashayya, historically part of the Ottoman Vilayet of Syria, became part of the newly established Lebanese state. Naturally, there was marked resistance to these new realities. Thousands of those living in the newly-constituted Lebanese state protested in Tripoli, Sidon, and the Bekaa, but to no avail.

When the forces of al-Atrash crossed into Lebanon on their way to Rashayya, plenty of residents from the surrounding villages joined in the revolt. The arbitrary drawing of a border between two entities didn’t immediately translate into their residents’ adoption of the nationalist identities on each side. Historians have written about how Druze fighters from both sides of the border engaged in sectarian violence, killing thousands of Lebanese Christians, expelling thousands more from their homes, and causing an international crisis for France. Members of the Lebanese diaspora in the Americas criticized the French for failing to keep their promises, as the protectors of Lebanon’s sovereignty and of its beleaguered Christians.

But the pictures depicting the Battle of Rashayya, displayed next to those celebrating Lebanon’s independence, don’t necessarily subvert the national mythos. Ultimately, Lebanon and Syria continue to exist within the exact borders hastily drawn by Gouraud. But what this exhibit—and exhibit within the exhibit—really does, is to display the dynamism of our contested pasts. It reminds us that our present condition is not endemic or sterile. It affords us the physical, political, and mental space to reimagine both Lebanon and Syria’s futures, particularly at a time where the avenues for change in both countries continue to be shut down.

Since my visit to Rashayya in 2019, Lebanon’s leaders have led its economy to ruin, while their negligent sectarian governance resulted in the explosion of the port of Beirut in August 2020, leveling half the city and killing over 100 people. On the other side of the border, Bashar al-Assad refused to abandon the presidency he inherited from his father in the wake of the Syrian Revolution of 2011. Since then, Assad and his Iranian, Russian, and Lebanese allies oversaw the total destruction of Syria, the murder of over half a million Syrians, and the displacement of more than half the country.

Our tour concluded, we emerged into the citadel’s courtyard. Our guide asked us earnestly why we’d come, and which parts of the country we were from. This is a familiar Lebanese social practice: by learning where we were from, our guide could discern our sects and thus, our politics; a delicate dance, undertaken whenever a set of Lebanese strangers have occasion to meet.

We told our guide that we were sightseeing city dwellers, interested in hiking up the mountain, and asked if she could recommend a local guide. Her face turned to Mt. Hermon’s imposing peaks, and she sighed. She knew a guide, she said, but it was almost impossible to go without the army’s approval: a few months before, two local boys from Rashayya had gone up the mountain, and lost their way. They’d been kidnapped and held at gunpoint by the Syrian Army checkpoint on the other side. It had required a monumental effort from local dignitaries, Lebanese army and state officials to persuade the Syrian regime forces to release these terrorized young men. Syrian troops rarely release their captives.

Our guide explained that since the Syrian uprising and subsequent civil war had begun, the regime forces stationed atop of Mt. Hermon had grown more erratic, and the paths through the mountain had become a lucrative smuggling route. It wasn’t safe to go up there, not from Lebanon.

Inside, the exhibition blurred the lines between competing nationalist histories, commemorating an era where locals brazenly resisted borders established by colonial schemes. Outside, a mere stone’s throw away, the actual borders between the countries are rigid. I fear that inelasticity will soon overwhelm the imaginations of those who live here.