If you’ve ever taken a closer look at the weird-looking crossword puzzles in a UK newspaper or in the Financial Times, you might think that the clues don’t seem to have anything to do with the answers. But there’s more going on in a cryptic crossword than what you see on the surface.

The magic of solving a cryptic crossword is in the joy of discovery. It’s a playful, thought-provoking, confounding, and strangely amusing pastime—a world away from solving standard crosswords, where, in all but the most subtle examples, cleverness and wordplay take a back seat to the exercise of memory and a kind of pattern recognition. Solving a well-set cryptic clue, on the other hand, evokes some dizzying mixture of admiration, rage, exasperation and laughter, plus a special delight—a kind of intellectual intimacy and elegance unmatched, we think, by any other kind of puzzle.

Torquemada was the world’s first cryptic crossword compiler—by whom we mean Edward Powys Mathers (1892-1937), an English poet and translator who took the name of the marginally more fiendish grand inquisitor of Spain as his crossword pseudonym. The crossword Torquemada debuted this wonderful new art form in 1925 (according to Guinness) in The Saturday Westminster Gazette. Since then, compilers have kept the habit of publishing their works under grand and/or fanciful pseudonyms: Afrit, Janus, Bunthorne, Custos, Mephisto, Ximenes, Everyman, Azed.

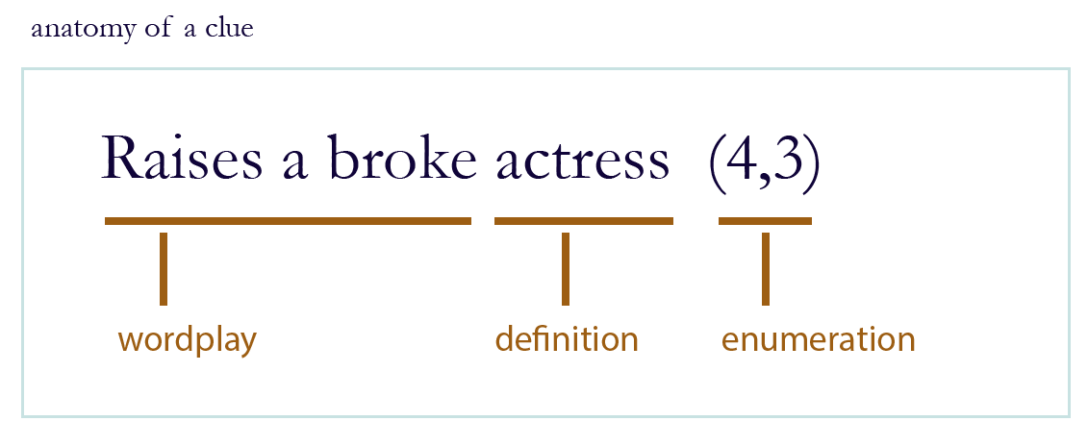

The conventions and tricks of solving these puzzles have changed over time, but certain features are consistent. (Always keep in mind that the compiler is trying to fool you and drive you insane.) First, cryptic clues contain two parts: the definition and the wordplay. (They’re followed by the enumeration, which is just the number of letters in the answer).

The definition is generally either at the beginning or end of a clue, and part of the joy is puzzling out how the parts fit together. The answer we seek might mean “raises,” or “actress,” or “a broke actress,” some part of either the beginning or the end—that’s what we have to discover. In this case, we’ll spoil it, and reveal that the definition is “actress,” so the wordplay is “raises a broke”—what could that possibly mean?

Well, by convention, there are certain common “indicator” words that solvers learn to recognise within a clue. Words like “broke”, “destroyed”, “exploded” and “smashed” generally indicate an anagram; they’re telling us that the other letters in the wordplay will be “broken up” (and then put back together in a different order). Here, “Raises a broke” means “[break up] raises a.”

The definition tells us that the answer must mean actress, and that it’s (4,3) letters long. Two words, and so, perhaps, a first and last name, which together are an anagram of the letters r-a-i-s-e-s-a.

Got it? It’s the actress Issa Rae, of Awkward Black Girl and Insecure fame.

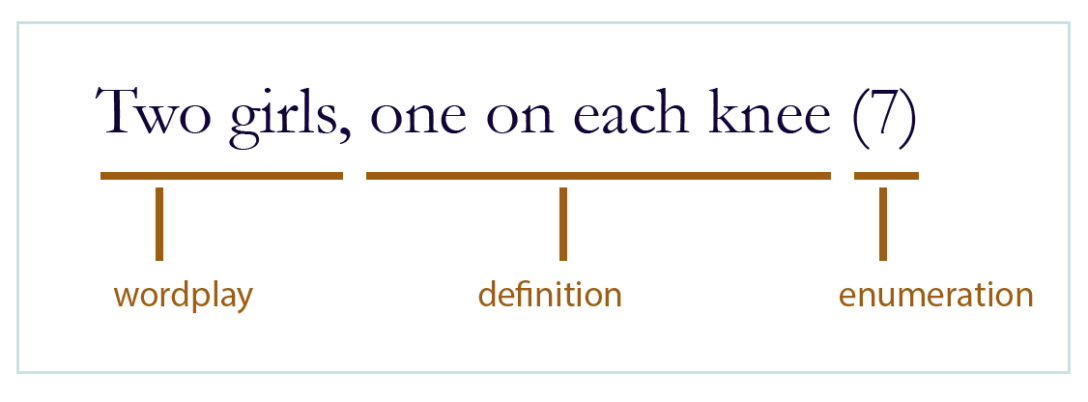

But things can get far more complicated and subtle. Here’s a very famous clue:

This one was set in 2007 by Roger Squires (known as Rufus in the Guardian, and Dante in the FT); the solution is PAT-ELLA (you have one on each knee).

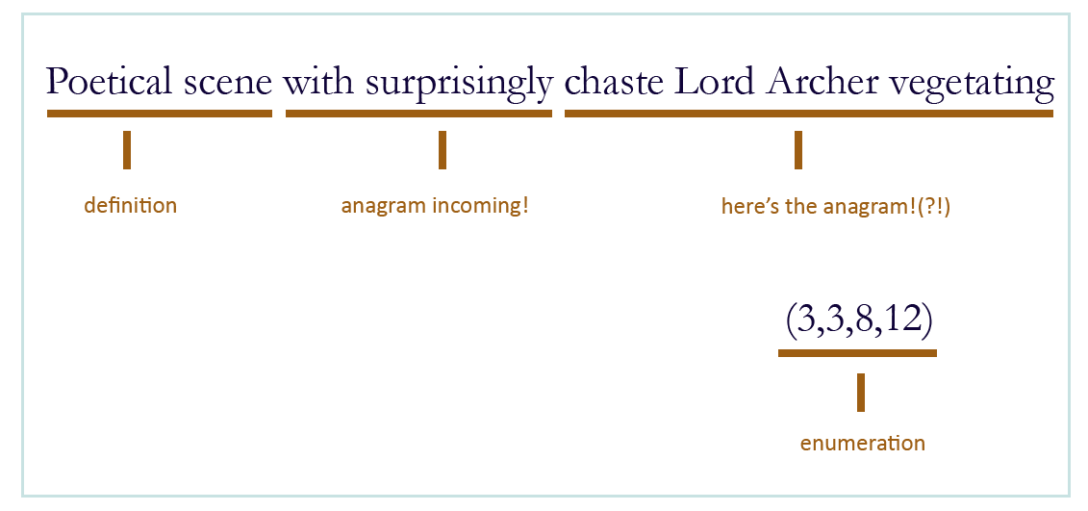

The Reverend John Galbraith Graham MBE (1921-2013), who set crosswords as Araucaria (the name of the monkey puzzle tree) and Cinephile (an anagram of ‘Chile pine,’ another name for the same tree) was the generally acknowledged master of the form in our times, wildly erudite and yet endlessly gentle, with an inventive, wicked sense of humor. Before his reign over the world of crosswords, he served as a navigator in the RAF in WWII, and later became a curate.

Araucaria’s obituary in the Guardian praised his famous long anagrams, including this one:

Few people in the world would have seen that anagram coming, but even mere mortals, with patience, might discover enough of the other clues that the fog would begin slowly to lift—revealing at last the pristine form of “The Old Vicarage, Grantchester” somehow emerging from “chaste Lord Archer vegetating.”

There is something magical about the way that the clues can be so short and so crisp, but contain so much information. In fact a favorite clue from Bunthorne (a compiler from the UK, where they play pretty fast and loose with the setting rules) is just:

B (6,6)

… the answer being, “bottle opener.”

Crosswords as a whole are more recent than you might imagine; the first recognisable one was created by Arthur Wynne, an Englishman living in America, for the New York World in 1913. By 1942, cryptics were so popular in Britain that they were used as a recruitment tool to find codebreakers for the war effort at Bletchley Park; the story that Alan Turing himself set a puzzle seems, alas, to be only fiction.

The norms and conventions of the art were codified by Alistair Ferguson Ritchie, known as Afrit, in his 1946 book Armchair Crosswords, with such stipulations as:

“We must expect the composer to play tricks, but we shall insist that he play fair. The Book of the Crossword lays this injunction upon him: “You need not mean what you say, but you must say what you mean.””

In the US, there’ve been several attempts to start a cryptic revolution. The composer Stephen Sondheim was a major pioneer, writing “How to Do a Real Crossword Puzzle” for New York in 1968, and setting a number of puzzles of his own. The New York Times has run occasional cryptics since the late 1970s, and the New Yorker started a regular cryptic in the 1990s. But despite these various green shoots, the cryptic craze never quite took hold—though a change may be coming. The New Yorker re-issued their cryptics online beginning in November 2019, before announcing (to great excitement among American crypticionados) a series of new weekly puzzles in July 2021, with your author Stella as one of the setters among an all-star cast. The New Yorker now joins the long-pioneering Out of Left Field and our own publication, The Browser, in putting out weekly American cryptics, so we feel confident in saying the American Cryptic Renaissance (or possibly just Naissance) has arrived at last.

Out of Left Field’s solving guide, Word Salad, walks you through the conventions around the different types of clues. If you have a New York Times games subscription, the archives of the Variety Puzzles offer some fairly approachable cryptics. The #CrypticClueADay hashtag on Twitter gives you a chance to practice solving individual clues.

The lover of cryptic crosswords grows to know the mind and heart of his favorite compilers, and to conceive a great affection for them. Thus it was that in January of 2013, Araucaria, who was then 91 and still as sharp and as beguiling as ever, brought great sorrow to millions of cryptomaniacs with clue 18 Down of Guardian crossword No. 25,842: Sign of growth (6), the answer being “cancer.” The rest of the puzzle explained that he’d been diagnosed with oesophageal cancer, and was being treated with palliative care. He died the following year. But those of us who learned the art from him will remember him forever, every time we tease out the clues of a good puzzle; the kind with wild anagrams and puns, jokes about movies, botany and disco dancing, clues where the whole answer is spelled out right in front of you and you don’t even notice, until all of a sudden, you do, and leap out of your chair, shouting in triumph.