“I’ve heard about space for a long time now,” the actor William Shatner announced last week on the blog of Blue Origin, the space exploration company founded by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. “I’m taking the opportunity to see it for myself. What a miracle.”

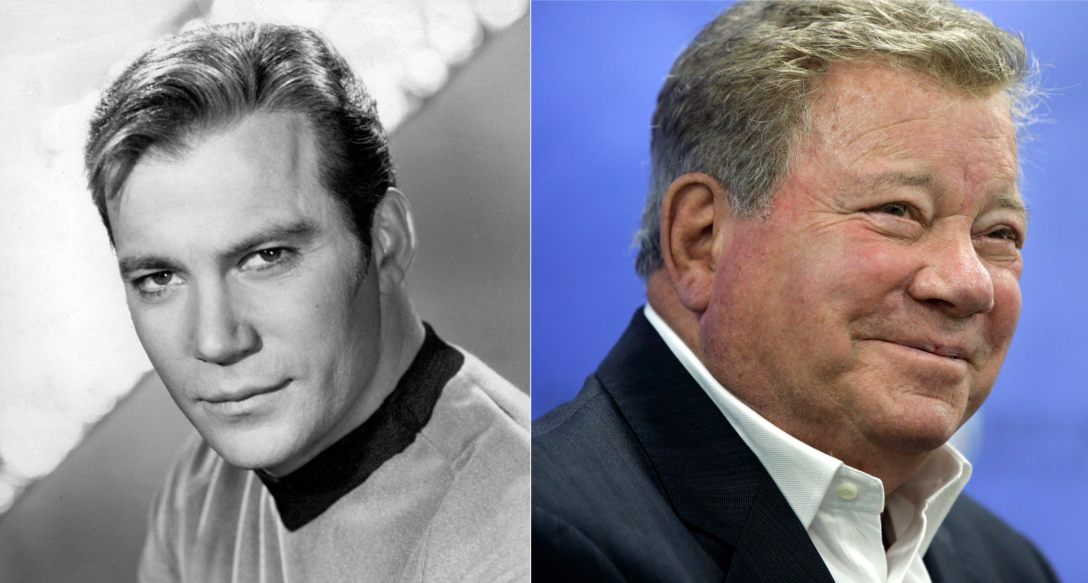

These remarks are conspicuously lacking in the high-flown touch of the late Gene Roddenberry, creator of Captain James T. Kirk, the beloved character played by Shatner on Star Trek; Roddenberry was given to making dreamy pronouncements like, “The human adventure is just beginning.” In any case, Life is scheduled to imitate Art on Wednesday, when the 90-year-old Shatner will be blasting off on Blue Origin’s New Shepard suborbital launch vehicle. The cinematic spaceman, by spending ten minutes in (or at least near) space, will represent the embodiment of an “exploration of futurism” in a monumental performance of nostalgia for the early, romantic days of space travel, and for the glamor and sense of discovery conjured by the memory of Captain Kirk on Star Trek.

In this way Shatner’s space flight isn’t so much a PR gimmick as it is a fashion statement; he’s like a mascot, or like a Starfleet badge for Amazon founder Jeff Bezos to wear almost as cosplay. And it won’t be the first time; the billionaire’s lifelong devotion to Star Trek is well documented. He appeared as an alien in the 2016 film Star Trek Beyond, and a few years ago Redditors traced the whereabouts of the original 8-foot studio model of the Starship Enterprise to the lobby of Blue Origin’s headquarters in Kent, Washington.

Years ago, Shatner told the BBC he’d declined the invitation of Richard Branson, another billionaire space mogul, to fly into space on Virgin Galactic, claiming he’d been asked to pay for the privilege. “He wanted me to go up and pay for it and I said: ‘Hey, you pay me and I’ll go up. I’ll risk my life for a large sum of money.'”

Last week, John Herrman reported in The New York Times that Blue Origin said that “Mr. Shatner would be flying ‘as our guest’—meaning he didn’t pay for his ticket.” But just how much is it worth to Blue Origin, already the vanity project of a galactically self-absorbed man, the richest on earth, to appease his vanity with the childhood dream of being space pals with Captain Kirk?

Bezos’s own performance as a spaceman this summer was roundly mocked. His cowboy hat alone made it plain how concerned he was with the figure he would cut before the cameras.

Marina Koren’s shrewd take at The Atlantic on Elon Musk’s most recent SpaceX launch likewise spoke of the style of billionaire space tourism. Describing the recent Inspiration4 commercial mission, she noted that space travel has become “a real customer experience. You can see it in the Dragon’s interior—the minimalist design, all clean lines, with touch-screen displays and cushy fabrics.” Textures, design, lines—being in space comes with a certain futuristic look, recalling movies like Ex Machina, or a hotel designed by Philippe Starck.

Science and technology drive space travel, but getting people to care about it requires skill in manipulating certain aesthetic registers: futuristic fantasies must be visualized, projected into the collective imagination in an elegant way to stoke excitement and feelings of awe, every bit as much as they need to be realized, tested and fine-tuned by engineers. Shatner’s voyage with Blue Origin keeps this admixture swirling. As the New York Times reported, audiences will witness a “blurring of reality and fiction.”

This helps explain why Kara Swisher, in a recent interview for Sway, kept trying to pin down David Eggers on what it would take for him to join a launch, suggesting that it would be a significant matter for a novelist to visit space. “What would you do if Jeff Bezos offered you a seat on his rocket ship, for example?” she asked, a question tangentially related to his latest dystopian novel The Every.

“I’m always a fan of space exploration and I’m the biggest NASA geek,” he replied.

And so anything that moves the ball forward a little bit there—I think that the absurdity of Bezos spending what could have been people’s wages on a rocket is—no one could have satirized that, especially the phallic rocket. It’s so far beyond Mike Myers… But overall, when Richard Branson does his rocket, I want to see it. I want to see what Elon Musk is doing with his rocket program. I think that there is a way to do it that is valuable to humanity.

Even through his equivocations—“anything that moves the ball forward…there is a way to do it”—Eggers seems to acknowledge that space travel is not just about flashy tech; it’s about image and messaging as well as political realities, and the idea that exploration itself might prove to be “valuable to humanity.”

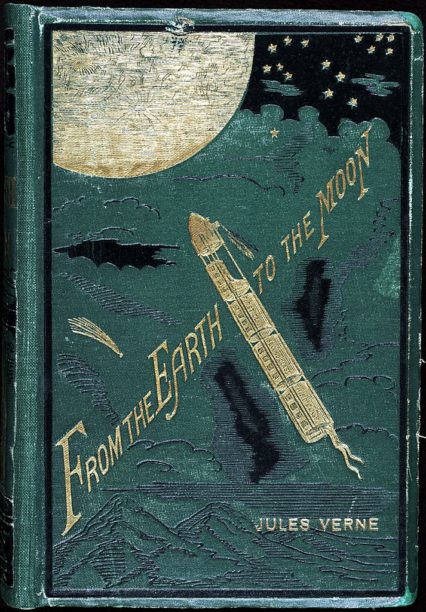

public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsStories and art about space travel significantly predated the real thing, but it’s been about spectacle since the days of Jules Verne; it’s rhetorical—and entertaining. Russia is about to make the first ever fictional movie filmed in space. Not to be outdone, last year NASA announced a collaboration with Tom Cruise to film its own movie in space: “We need popular media to inspire a new generation of engineers and scientists.” Young technologists are as inspired by the rhetoric of fashion, art and storytelling as anyone else. The danger is that the irresistible seductions of minimalist design and special, fancy costumes with your name embroidered on the chest will overwhelm what is essentially a pernicious message.

Virgin Galactic’s Richard Branson boasted after his company’s first fully-crewed launch that “the new commercial space industry is poised to open the universe to humankind,” to which the author and game designer Ian Bogost replied dryly, “This is the opposite of what has happened today.” It’s painfully obvious that Branson’s rocket ship is for the very, very few. But it can—indeed it must—look cool to all “humankind,” so long the elite are the ones who will benefit.

In my neighborhood art museum gift shop recently, I spotted a toy called “Build Your Own Mars Colony” (“Simply unfold the poster to reveal the surface of Mars, pop out the pieces and assemble them, no scissors or glue required, for hours of extraterrestrial fun.”) The toy is “creative” and playful, and though it celebrates the instrumental and scientific, it incorporates aesthetic elements of “design.” Midway through Kim Stanley Robinson’s monumental novel Red Mars, a minor character dismisses the job of colonizing Mars as “artwork.” This idea echoed in my head as I pondered the little cardboard kit.

Around the same time, I saw a headline about NASA paying people to spend a year living in a simulated Martian habitat. The article at Business Insider led with an “artist’s rendering” of a simulated Red Planet. In mid-2021, well into the second year of the COVID pandemic, the futility of this fantasy was almost palpable. As if living on Earth wasn’t hard enough! Somehow the government had decided that it was worth paying someone a salary to pretend to live on Mars. The more immediately beneficial fantasy would be to pay people to live on Earth. But that would not be a spectacle, something to watch. (On the other hand, simulated Mars habs are a topos already rife with earthbound drama.)

Lego currently offers not one but two sets featuring the Space Shuttle, an outmoded vehicle that nevertheless continues to captivate the imagination—not as functioning technology, but as a symbol. Legos are toys, but they are also cultural artifacts, even a kind of art; the company increasingly recognizes this as their fans age into adulthood. After last summer’s first successful SpaceX launch of the Dragon with astronauts inside, the capsule was christened the Endeavor, in homage to the retired Space Shuttle—keeping the ambience of the program alive in name, if not in form. The Space Shuttle is the image of a dream we’re desperate to keep alive, of American ingenuity, frontiersmanship, daring and future-mindedness.

This brings us back to SpaceX’s recent launch, the Inspiration4 mission. Elon Musk’s company no longer needs to publicize the spectacle of a successful launch: this is old hat. The latest mission had a new appeal, though: it was the first time four civilians went up in space, opening the market up to commercial launches. When the space tourists returned safely to Earth, a new type of commodity came into being, a new, almost inconceivably rare new look to wear (no matter if the SpaceX outfits are themselves derivative, somewhere between Biker Scout chic and bleached Daft Punk.) Yet space fashion is already utterly effete, worn out, as the choice of the 90-year-old Shatner for Blue Origin’s launch—paying homage to the 57-year-old Jeff Bezos’s personal nostalgia for Star Trek—so clearly demonstrates. Not only have the billionaires stolen our space sex, they’re recycling space style, in a kind of billionaires’ Buffalo Exchange.

On my eighth birthday, the space shuttle Challenger exploded. We were sitting in our classroom watching the launch on TV, eating Cheerios out of little paper cups. A teacher, Christa McAuliffe, was on board; it was supposed to be a historic moment. But not in this way. The visual, aesthetic registers of space flight, the explosion and spiraling wisps of white smoke, were burned into my inner mind in that moment. How it looks, versus how it’s supposed to look. It was and is a story of human ingenuity and courage, discovery, the leading edges of science and technology. But the Challenger disaster unexpectedly became the story of how we visualize each precarious, potentially treacherous journey beyond our atmosphere. It’s a story of what our space voyagers look like—and when such looks take on new meanings.

Kennedy Space Center, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Kennedy Space Center, public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsFashion and design can revolutionize the way we inhabit space, or move in our bodies. But these things can also be banal, numbing, fascistic. The aesthetic intrigue of space travel is fading now—throttled, like so much else, by the choking effects of excessive wealth and human narcissism. It is starting to seem more and more like a ratty and recognizable affect. Space travel: that entertaining look that billionaires give off. Rare, and hopelessly uncool.