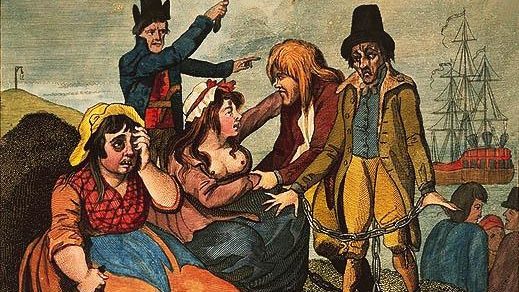

Like all the best propaganda, it involved jaunty music, and synchronized movement from people dressed identically. It was all folded into the postcolonial pastie: we sang “Oh, Danny Boy,” and songs about sheep theft, and about the brolga. We wore the convict pajamas darted with arrows, we panned for gold at Sovereign Hill, we ate scones, we read about the Dreamtime, we bugled, we sausage sizzled, we visited a sunken likeness of Ned Kelly lying in a cot. A rubbish bin next to a couch cushion—our history! In the school hall, we faced a portrait of our far-off monarch in a lemon gown with a sprig of wattle on her shoulder. Our young mum back in England!

Anybody remember convict pyjamas?

I had those same convict pj’s that Angus is wearing in this clip when I was a little kid

Hahaha

early 70’s Australian culture …

tweeted by Russell Crowe (@russellcrowe) on April 14, 2020.

I spent hours as a child hoisting the sails and climbing the Jacob’s ladder while singing along with the convict folk song “Botany Bay.” Many mornings, primary school in Canberra in the mid-80s started this way: 150 children with boomerangs on their chests gathered for Health Hustle, jerking our bendy green spines on the diagonal as we sung, for we’re bound for Botany Bay. It didn’t matter, or occur to us, that we had each been born right there, we pistoned our arms and legs up and down into the next verse, reenacting our colonial banishment: Farewell to old England for-eh-eh-ver.

We have been singing about leaving England my whole life. It gets cut on the radio, but the opening minute and a half of Split Enz’ “Six Months In A Leaky Boat” consists of a sailing montage, which wobble-fades to a Finn brother and a guy in a captain’s hat doing a jig in Aotearoa. Like other colonial vestiges, the meaning isn’t clear, beyond something about the “spirit of a sailor.” Flotillas of drunken Australians are forever washing up on the shores of Europe in non-pandemic years under the banner of Contiki, named for the Norwegian voyage across Polynesia. Ach, the tyranny of distance! we say as we decide to live in a treehouse among the coffee beans in Bali. Even the Australian national anthem, which is about as stirring as a canned keyboard demo, calls out to “those who’ve come across the seas.” We are the lucky country, girt by sea, because it’s all an accident, really, our being there — us being the British, only lately having realized that it was not our land and that, now we’re here, we’d rather stop the boats. The poor convicts! said the teachers mouthing along and reaching their hands into the sky to grab hold of the invisible ropes of tall ships.

“Right glad to have the prospect of soon setting foot on terra firma after 90 days confinement aboard the Birmingham and never having had the the satisfaction of seeing land from [the] time we lost sight of the Welsh coast till we got the glimpse of this far-off world,” wrote migrant Andrew Hamilton in his 1852 diary, quoted in Andrew Hassam’s Sailing to Australia: Shipboard Diaries by Nineteenth-century British Emigrants. “i could not help reflecting it was a cruel destiny which had thus compeled us to leave our nativeland our friends & homes to face we knew what in a foreign land,” wrote the passenger Abijou Good in 1863. These diaries were often addressed to family members left behind, and helped emigrants process their free-floating identities in that place between the rite of separation and the rite of incorporation, as Hassam calls it. “Often the handwriting in a diary will get progressively smaller as the diarist begins to realise that the voyage may not last a single volume,” he says.

The early days of voyage were frequently “less coherent” thanks to seasickness, and the diaries not terribly introspective (Hassam thinks this is because it was pointless to worry about an irreversible journey), and so the anxieties come out in other ways, in passages on storms or sunsets. Captain James Cook (frequently graffitied into “Cock” in the Canberra, Ngunnawal country, suburb of the same name) writes forlornly of two episodes involving birds in his own diary of sailing the Endeavour south:

“… the wind becoming fair, we got under sail, and put to sea. On the 31st, we saw several of the birds which the sailors call Mother Carey’s Chickens, and which they suppose to be the forerunners of a storm; and on the next day we had a very hard gale, which brought us under our courses, washed over-board a small boat belonging to the Boatswain, and drowned three or four dozen of our poultry, which we regretted still more.”

The birds receive equal space in Cook’s diary to the master’s mate, who dies after being dragged into the sea with the anchor rope (“the body came up intangled in the buoy-rope, but it was dead”). There is a lot of ink spilled on the colours of fish.

The authors often apologize for the boring nature of their letters and diaries; their thoughts pass through like water through the bilge. A woman goes mad in Janet Frame’s novel The Carpathians, arriving in New Zealand by plane “without having her mind bathed in the enduring image of the seas that extend, like the seas of eternity, between country and country.” Everyone is affected by colonialism, wrote the authors of “The Empire Strikes Back,” most certainly those who have been colonized, but also those raised to believe that they lived in a distant southern England, same same but spiky and terribly dry:

The alienation of vision and the crisis in self-image which this displacement produces is as frequently found in the accounts of Canadian ‘free settlers’ as of Australian convicts, Fijian–Indian or Trinidadian–Indian indentured labourers, West Indian slaves, or forcibly colonized Nigerians or Bengalis.

Follow it, and the displacement trickles all the way down to the Aranda Primary Health Hustle—a school inconspicuously named for an Aboriginal tribe based hundreds of kilometers away in Central Australia—singing toorali-oorali-addity.

In the early twentieth century, the invention of aeroplanes allowed mail carriers to deliver migrant correspondence faster. Inevitably, passengers started hitching rides on postal flights, removing the need for narration, and commercial airliners—originally called “flying boats”—arose to fill a new market shipping people here and there. These were sleek and exciting, and had seatbelts, so fast was the journey. TWA began to advertise a mindset of “There Today, Home Tonight,” transcending space, time, territory, and the question why-the-hell-not?

By the mid-20th century, there were posters advertising travel itself as identity. In “A plane man’s guide to Belgium,” we learn that “he’ll help you shake the soil of little old Britain off your feet and fly.” His 21st-century descendent might be the girl sitting first-class on her way to ruin Tulum in a turquoise Juicy Couture sweatsuit. Gradually, throwing off your home country to psychologically occupy another became cheaper and cheaper, faster and faster, something you might do deliberately, rather than out of necessity.

My early ancestors exited their known worlds in Scotland and Ireland by boat; by the 1950s, my Australian grandfather was a captain on one of the first Qantas flights to perform the Kangaroo Hop from London to Sydney (via Lydda, Karachi, Colombo, and Learmonth), drawing two disparate points closer together—now just a hop away!

It changed the way we conceive of distance. Jerry Seinfeld riffed on this some years ago:

It’s amazing to me that people will move thousands of miles away to another city, they think nothing of it. They get on a plane, boom. They’re there, they live there now. Just, uh, I’m living over there. You know, pioneers, it took years to cross the country. Now, people will move thousands of miles just for one season. I don’t think any pioneers did that, you know. ‘Yeah, it took us a decade to get there, and, uh, we stayed for the summer, it was nice, we had a pool, the kids loved it, and then we left about ten years ago and we just got back. We had a great summer, it took us 20 years and now our lives are over.’

As a ski bum looping U.S. and Australian winters, I would spring the extra money to fly Qantas just so I could be served Tim Tams by someone who sounded like they grew up boogie-boarding at Collaroy. I was on a ship that, a few hops earlier, might have been piloted by my grandfather in one of those hats from the Split Enz video.

Itself a descendent of the British Overseas Airways Corporation, Qantas understands the pull of nostalgia for here or there or somewhere. Since the ‘90s, the company has used the Peter Allen song “I Still Call Australia Home” to rouse in our throats a scritch of longing for the moment “when all of the ships come back to the shore.” We are travelers, but also upwards of a quarter of Australians were born somewhere else; more of us come from India now than anywhere else, with China second and the UK now a distant third. The messiness of the Australian diaspora became obvious during the pandemic, with the border closed and planes grounded, a million citizens living abroad, and bureaucrats making seemingly arbitrary decisions about where to send repatriation flights, whether to evacuate Afghan allies, whether dual citizens were “real” Australians, and to whom to pledge our mateship.

As COVID prepared to set sail in prosecution of its voyage, to borrow a Cookism, my sister informs me that the prime minister, a stout Large Grown Son with the spirit of a boarding school bully, had hoped to splurge some sovereign coin on sailing another replica of the Endeavour around Australia for the 250th anniversary of Cook’s arrival. Never mind that we had already made a replica and tootled it over to New Zealand back in the ‘90s, or that the Endeavor never circumvented the country–or that it precipitated a genocide. People felt compelled to deface monuments of Cook (Cock) in the wake of the cringe $7 million proposal, and I could laugh, but I was still two years behind the punchline.

Mid-pandemic, my husband and I moved north from New York City to the place where the Hudson river is shoveled into the first lock on the Erie Canal. My surrounds began to nettle me more than usual; the shapes of the trees, the triangular scones, the alien English language (a lawn sign near where I live reads “WHAT IF BIBLE TRUE”). Alone in my Victorian house, I teared up to John Farnham. When I’m homesick, it’s impossible to explain to my husband, here, in this cluster of colonies, exactly what it is I miss. The wattle? Laksa? Taking the piss?

Travel tells us we can be everywhere, we can feel a special “tie” to the Amalfi coast, because it’s pretty and we’ve been there a bunch of times to holiday; we don’t have to pick one land. But what if the oceans are still too big? What if there aren’t enough boats? What if a wave sweeps away the chickens? All I can manage is to sweat and mime the climbing of the cargo ladder.

Recently, I read the story of the Taroom Star, an Aboriginal groove stone stolen decades ago by a white guy in Queensland. He intended on returning it to the Iman people, who have largely moved on from the area after a massacre in the mid-twentieth century. He ran out of time, however. After his death, the man’s son decided that, rather than hauling the stone out in a ute, he would build a cradle for it, and bridge the 500 kilometers to Taroom on foot.

An Iman woman heard about the trek, and travelled from Melbourne to see the rock returned home. “I can’t speak my language and I don’t know all my ceremonies,” she told the ABC. Iman people from all over returned to the area, and they led the last stretch of the journey, flanking the stone step by step over the red dirt. They gathered in ceremonial dress, burning smoke, and ushered the star back into its homeland. Many wept. “The stone has come back,” they said.