“Stop by my office when you have a minute,” read the email from my boss, with the rather ominous-sounding subject line, “Your post on Next Door.” Since I often reply, “Racism” to the Nextdoor posts in my neighborhood asking things like, “What’s going on with this suspicious looking guy?” I figured my trolling days had finally come to an inauspicious end.

Fortunately, he just wanted to talk about how batshit crazy these people are. In an area where there are very few shootings, they manage to turn any loud noise into a spiraling conspiracy about a gunfight that must have taken place just south of us, where nonwhite people live.

In 1964, Richard J. Hoftstadter attributed the elevation of Barry Goldwater by the GOP in the 1960s to “the paranoid style in American politics.” Hofstadter called the paranoid style “an old and recurrent phenomenon” in U.S. public life, characterized by “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy.” He quoted a newspaper article by way of illustration.

. . . It is a notorious fact that the Monarchs of Europe and the Pope of Rome are at this very moment plotting our destruction and threatening the extinction of our political, civil, and religious institutions. We have the best reasons for believing that corruption has found its way into our Executive Chamber, and that our Executive head is tainted with the infectious venom of Catholicism. . . minions of the Pope are boldly insulting our Senators; reprimanding our Statesmen; propagating the adulterous union of Church and State; abusing with foul calumny all governments but Catholic, and spewing out the bitterest execrations on all Protestantism. The Catholics in the United States receive from abroad more than $200,000 annually for the propagation of their creed.

This passage appeared in a Texas newspaper in 1855.

After McCarthy, and after Goldwater, the paranoid style remained visible in the Republican ‘conservative movement’ from Goldwater’s appointed successor, Ronald Reagan, through to Fox News, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump. That’s why the paragraph above looks just like something you might see today on a QAnon post, maybe with Soros subbed in for the Pope. And slowly, over the last half-century, the paranoid miasma has seeped all the way through U.S. culture and into the way many in the U.S. see our neighbors. Or maybe it has always been there, waiting just behind the white picket fence.

screenshot: nextdoor

screenshot: nextdoorMore than once, by inflating a bike tire with an air compressor, I’ve inspired locals to post “shots fired” on Nextdoor. Unfortunately, I have heard real shots fired, including directly at me, and they don’t sound anything like an air compressor. But the paranoid style can, through its own bizarre imaginative gymnastics, turn anything into evidence supporting fantastical fears and prejudices. Hofstadter called this the “big leap from the undeniable to the unbelievable.”

One poster took off to attack her neighbor with a baseball bat when she heard a cat and a power tool, and combined those sounds with her own paranoia to make the imaginative leap from coincidence, to abuse, to the urgent need for violent intervention.

Paranoia isn’t created ex nihilo. “What is missing is not veracious information” according to Hofstadter, “but sensible judgment.” There’s no doubt, either, that this phenomenon is as evident on Seth Abramson’s Supreme Court fanfic threads as it is when my neighbors conclude that kids getting groceries must be about to defile their precious automobiles, because “I know this area has seen some car egging in the past.”

The paranoid sees evidence of a vast conspiracy at every turn, indeed they see history and the world as intelligible by conspiracy alone. They are dispossessed: “America has been largely taken away from them and their kind, though they are determined to try to repossess it and to prevent the final destructive act of subversion.” This is a perfect capsule description of Nextdoor in my neighborhood.

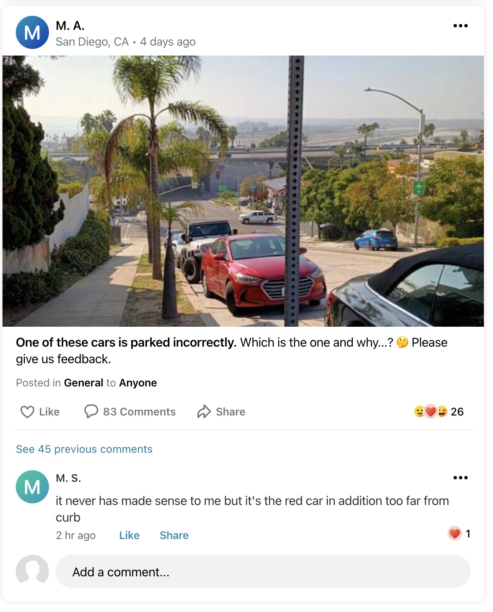

screenshot: nextdoor

screenshot: nextdoorHofstader looked at the right-wing conspiracy claiming that America had been “infiltrated” by communists intent on eroding individual liberties, destroying capitalism, and generally treading on snakes. The conspiracies in our neighborhood are somewhat more mundane, generally revolving around the presence of unhoused people and their role as vectors for everything from COVID-19 to crime, or electric bikes “taking out” other cyclists, to the assault on the sacred American right to a rent-free taxpayer-funded place for your car to live. Or pineapples. This is not, we are told, how it used to be.

Nextdoor isn’t alone; on “Neighbors by Ring” you can not only be casually racist, but also transfer vast amounts of personal information—your own, and other people’s—to Jeffrey Bezos and also the cops. And I don’t mean to pick exclusively on the right either, a lot of the folks near me were very much of the “Black Lives Matter, sure, but they went a little far when they stole some milk” persuasion, during the protests last year.

Just north of me, posters in Rancho Santa Fe (a rich, white area of North County San Diego) took things a little further last year, with some of them even volunteering to turn vigilante if the sanctity of a Target store were to be threatened. “Apparently the Target is already boarded up,” one community “Lead” wrote. Another member commented, “If anyone gets unruly or violent, I plan on coming with pepper spray and a stun gun to help the police… Looters need to be taught a lesson. If they get violent, we need to hit them back 10 fold and protect our community.” It’s like a ludicrous spy network composed of local folks who like to share intel on people who are not white, and who are walking to the shops with what they seem certain must be nefarious intent.

Chris Lehmann in The New Republic argues that Hofstadter could rightly be accused of being a sneering liberal, preferring to engage with the rhetorical rather than the material realities of modern politics. It’s a compelling point; Hofstadter’s writing is indeed symptomatic of the “fable of liberal powerlessness, bespeaking a failure of the liberal mind to adapt to radically altered cultural and political conditions.” This liberal arrogance crops up in his pathologizing of class differences, and it’s directly analogous to my Nextdoor neighbors’ yearning for a mythologized past by way of a Nextdoor lecture: “… here in Rancho Cucamonga we are an affluent neighborhood and this status should be reflected in our candy provisioned on Halloween.”

Right around the last week of May 2020 I was banned and/or deleted the Nextdoor app (probably for excessive reposting of the immortal video of the guy telling the LAPD chief “suck my dick and choke on it, I yield my time”). Luckily, though, the Best of Nextdoor feed keeps me up to date on “suspicious guys” and where to go on Halloween if I want some multiracial penis pops. The paranoid delusion of the day here in San Diego seems to be that old-fashioned dog-whistle warning that Accessory Dwelling Units are going to turn into “granny towers” and destroy “the character of the neighborhood.” Nevermind that the neighborhood has remained staunchly unchanged, because nobody my age can afford to buy a house here, excepting the vaguely evil few who work in tech, pharma etc. Yet, as Hofstadter says, the paranoid is not to be dissuaded from his fears, and instead “constantly lives at a turning point: it is now or never in organizing resistance to conspiracy. Time is forever just running out.”

Zillow made a robot to make it impossible for poor people to own homes. The federal eviction mandate was struck down by the Supreme Court. More and more people can’t afford a place to live, and more and more people are dying on our streets. These are the real threats to U.S. neighborhoods.

Nextdoor’s slogan is “When neighbors start talking, good things happen.” The truth is that good things happen when people do them together, instead of labeling our neighbors “suspicious guys.” The paranoid style, on or off Nextdoor, strangles the natural human desire to get out there and help.