Last September, while returning home from a birthday party on a motorcycle taxi around 9pm, some men of the Nigerian police force stopped me and my friend, John, a colleague with whom I study history. They searched our phones and when they could not find anything incriminating, they shoved us into a mini van and drove us to their station, where we were instructed to write a statement.

Our phones were seized and we were denied a chance to speak to our friends, who’d become very worried and kept calling us frantically. For more than two hours, we were made to sit in a waiting room with other young people they had arrested that night, who claimed that the officers had plucked them off the streets of Ilorin for no justifiable reason, as they had me and John. The one-year anniversary of the #EndSARS protests was only a few days away.

We sat on a long wooden bench with two other young men, facing a lanky officer who gathered our statements onto the rough pile of sheets on his desk. A lightbulb in the room flickered oddly. Another officer sat in a nearby corner, his gun visibly hanging out. A third, pot-bellied officer wandered in and out occasionally, as if supervising the proceedings. All the while our friends kept phoning us, but we weren’t allowed to respond.

John began to make small talk with the two others who’d been detained with us. They had already been waiting for several hours before we arrived. One of them, Samuel, a doe-eyed man who sported a big afro, owned a furniture shop in town. His companion, a short man whose name I cannot remember, talked more and laughed harder than everyone else. When Samuel’s girlfriend brought them food, he gave his own plate of rice and stew to us.

When we asked one of the officers why we couldn’t answer our phones, he told us to keep quiet. This was beginning to look like a kidnapping, I responded, raising my voice, adding that at least kidnappers permitted their victims to contact their relations.

This attracted the attention of a senior officer who had been making a final round before leaving for his home. He invited us into his office, where we told him we were journalists, and explained the circumstances of our arrest.

“Our men are like this sometimes,” he said. “I apologize on their behalf. I fear you journalists oo.”

At about 11:40pm we were released and allowed to go home, after writing our full names and phone numbers in a big, ragged book.

This hadn’t been our first run-in with the police. Early last year, while I was walking with John along the rail tracks in the rear of the bustling Challenge market in Ilorin, some policemen accosted us. John hadn’t completed a sentence about our rights when one of them slapped him hard across the face. I just stood there, dumbstruck, boiling with anger yet unable to act, lest they beat me too.

What gets to you when you are abused by authority in this way isn’t even the brutality, it is the debilitating powerlessness, the reduction of your will to a useless, insignificant thing. You bunch your fingers into a fist, your eyes tear up and you can only shake your head in helpless self-pity.

In retrospect, I consider us lucky to have survived the encounter at the market, and to have left the police station in one piece. The news online and in the dailies is replete with reports of unfortunate acts perpetrated by the Nigerian police. Many young people have died brutally after coming in contact with the police.

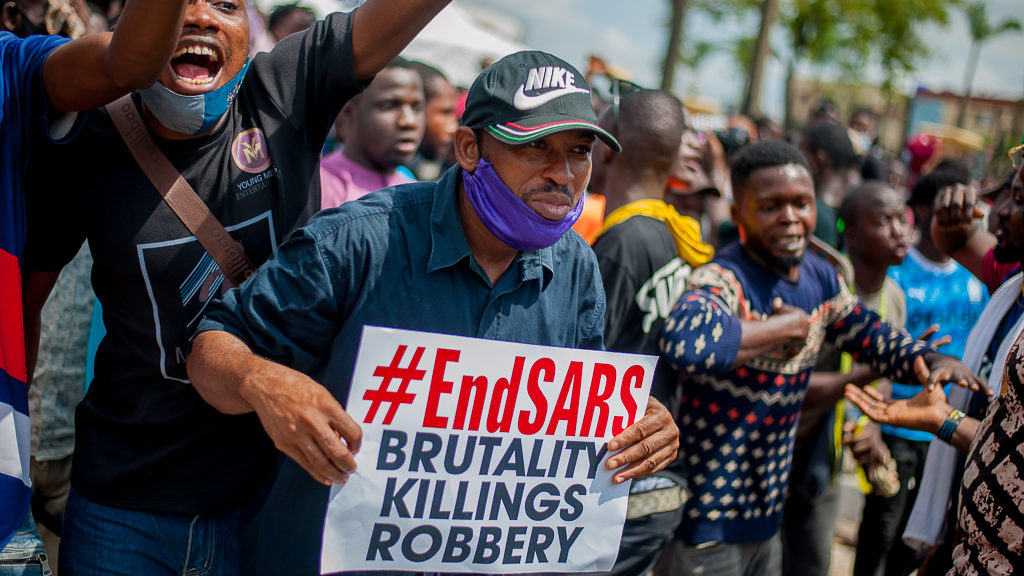

The Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) was founded in 1992 to combat highway robbery and kidnapping, but years down the line the organization went rogue. In October 2020, Nigerians took to the streets of the country’s major cities for nearly three weeks in protest against police violence and government corruption, which have been endemic since Nigeria’s independence in 1960. United under the hashtag #EndSARS, demonstrations swept the country.

The protests came to an end after the Lekki massacre, in which at least twelve people died, with many others injured and missing, according to Amnesty International. In the aftermath of the protests, SARS was disbanded, to be replaced by the new Special Weapons and Tactics Unite (SWAT), which citizens denounced immediately as a clone of SARS.

It is shocking that more than a year after the protests, the same abuses are still happening, and so casually. Extrajudicial killings, disappearances, police extortion, government failure and the embezzlement of public funds all continue unabated. Police are no longer seen wearing SARS vests and uniforms, but the crimes continue. The knowledge and daily experience of systemic dysfunction that propelled the original #EndSARS demonstrations continue to haunt the country like a ghoul, and young Nigerians still suffer the fear of the men in black, registering abhorrent encounters with law enforcement officers on social media.

Many young Nigerians, like me, view these latter events as evidence that our collective action has failed, at least in part. In other ways, the protest achieved its mark; it jolted the collective consciousness of the people back to life and inspired a new solidarity, which continues to this day.

Nigerians understand better now that their own freedom rests upon the freedom of their fellow citizens regardless of the differences between us in tongue, class or religion, at least. And I know that Fela, the grand patron of state rebellion, would be very proud of this from the high heavens.

Yet the government does not seem to break a sweat even though it has failed, not only in providing security, but in every point. Many months after the Lekki Massacre put an end to the #EndSARS demonstrations, the government continued to deny that there had been a massacre even in the face of dispositive proof. The government only acknowledged the killings last month, when an official panel released a document listing 48 victims of violence—including gunshot wounds, assault and murder—carried out by men of the Nigerian army. No apologies were issued as a result of the report, and no plan for restitution to the victims or their families was released by the government, which ultimately bears the responsibility for these crimes.

Several demonstrators arrested over the course of the protests are still languishing in jail, without trial. Others, like Imoleayo Michael, a young computer programmer, are facing charges of ‘conspiracy with others to disturb public peace’ and ‘disturbing public peace’ simply for raising his voice against police violence. Other protesters are likely to be discovered in the jails, since many demonstrators went missing and were never located during the #EndSARS movement (or worse—the body of Pelumi Onifade, a journalist killed while covering the protest, is yet to be released to his family).

Even though the #EndSARS panel featured some young people, and was constituted from across all states of the federation, justice remains a distant goal. Many recognizably criminal officers are known to be still in service. For many Nigerians, these panels represent mere government theatrics, and they will not quell the unrest.

Nigeria’s economy is a wreck, with sky-high unemployment and unprecedented insecurity. Highway bandits are abducting and killing travelers. Across the country’s south, there have been escalating calls for secession among factions of the Yoruba and Igbo, after years of exclusion, insecurity, and governmental incompetence. But instead of tackling dissent with meaningful solutions and better representation, the government arrested the champions of the secessionist groups.

Industrial actions have become the norm for trade unions of medical and academic professionals. Since the start of the pandemic, the National Association of Resident Doctors have gone on strike four times, leaving the people dangerously unprotected. Doctors are leaving the country in droves, leaving an already weakened medical system on the brink of total collapse.

In 2020, university students were forced to stay at home for ten months due to a strike by the Academic Staff Union of Universities in protest against nonpayment of wages. Local businesses supported by student custom were forced to close as students lost an entire academic year to the strike. Young people seeking to try the route of entrepreneurship are blocked by government policies, for example those prohibiting cryptocurrencies; social media platforms like Twitter are now banned.

Warsan Shire wrote in her poem home: “No one leaves home unless/home is the mouth of a shark.” These lines point all fingers to my country.

Emigration, called ‘jand’ or ‘japa’ in Naija street speak, has become the Nigerian dream for many young people. The failure to end police brutality, among the many other ills brought about by government incompetence, will continue to intensify the brain drain that is likely to continue in Nigeria for the foreseeable future.