A few years ago, actor and producer Ben Stiller was working on an “Untitled Oscar Levant Project.” I don’t know what became of it or if it will ever see the light of day. It’s a story that doesn’t lend itself easily to cinematic treatment. On the one hand, what could be more cinematic than the breakdown of a public figure? On the other, what could be crueler, in practice, than trying to tell Levant’s story using language that he himself had no access to?

It feels condescending and weird, and yet the fact that nobody knows about this guy has always pissed me off.

Because his story is so much about the problem of trying to succeed in this country.

In the words of one of Levant’s Mt. Sinai doctors: “He didn’t know why he ever tried to be a success.”

Levant himself, as usual, put it better: “It’s not what you are, it’s what you don’t become that hurts.”

Oscar Levant was a 20th-century pianist, composer, and interpreter of his famous best friend George Gershwin’s work after Gershwin’s untimely death in the late 30s. He wrote pop songs, including the jazz standard “Blame It on My Youth,” starred on a radio call-in show called “Information Please”, and was an unofficial member of the Algonquin Round Table in the 30s. He never fit in anywhere, and he was everywhere.

But he means a lot more to me than the sum of his achievements.

*****

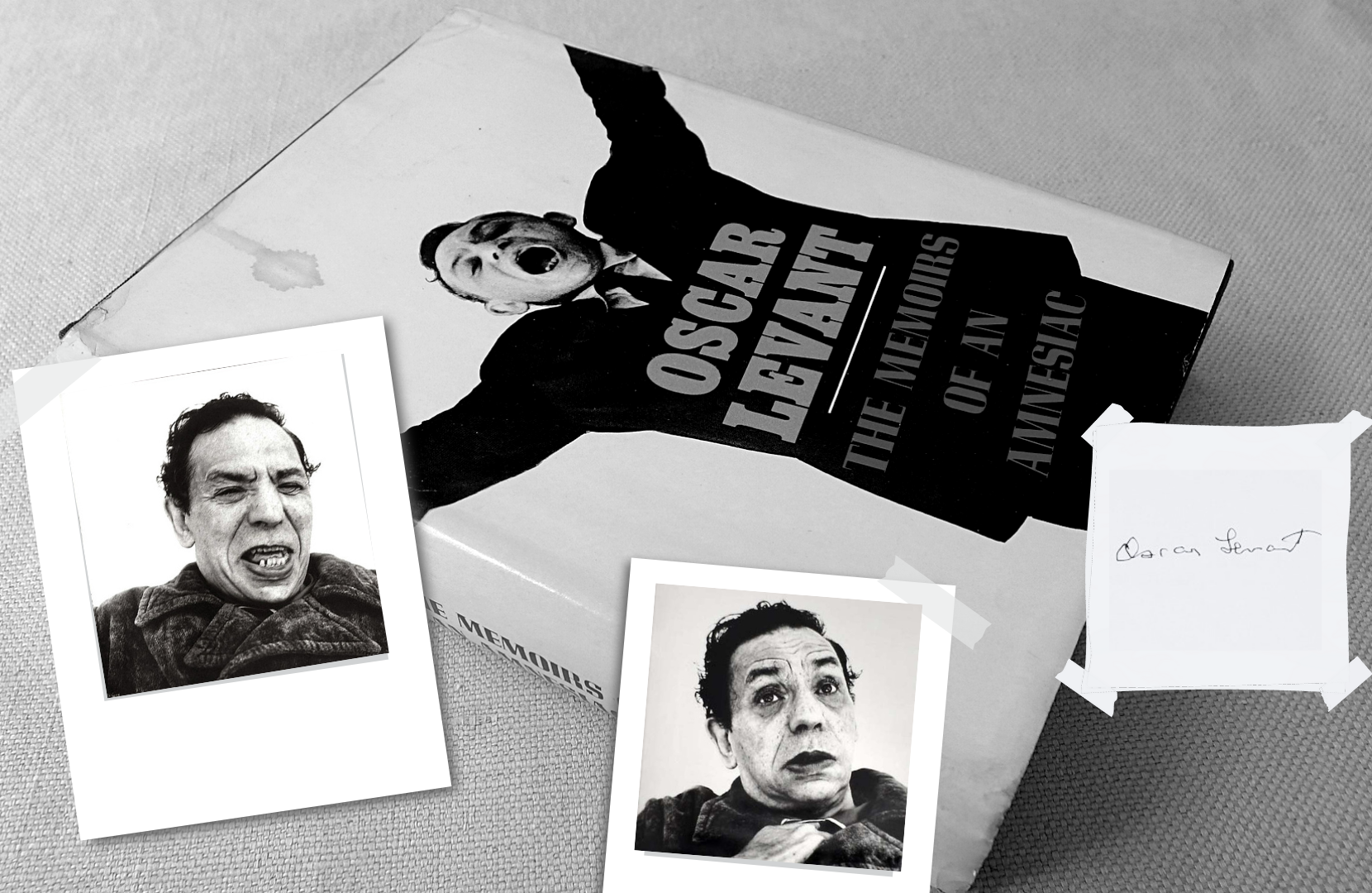

It seems weird to say, but the first thing that drew me to Oscar Levant was his face. Before I knew anything about him, I saw him, and I recognized something real. In his few film appearances, he appears a bit lost, a bit confused, a bit bloated. His is the kind of face that Hollywood only reluctantly gives screentime to, as long as it’s positioned off to the side of someone more aesthetically pleasing. In the case of 1951’s An American in Paris,—the film that gave me my first introduction to Levant—this is Gene Kelly, who tralalalas and traipses through a sound stage bearing only a cardboard resemblance to 1940s Paris. Meanwhile Levant, his burnout composer friend, sits in quaint cafes, behind a piano, clutching a too-small cup of coffee, expressing complete physical disdain for his co-star’s sunniness at every turn.

But it was Levant that I found beautiful. It was his face that spoke to me: too red and uneven, the lips full, the face beautifully Jewish, the teeth bad, the hair greasy. I couldn’t take my eyes off him, and I didn’t have to: there’s a part of the film that shows Levant in double exposure, playing every instrument in a full orchestra lineup. This is a dream sequence that, much like Levant himself, doesn’t really fit into the film at all. And yet it’s a microcosm of what the movie actually is: an hour and a half long excuse to celebrate the music of George Gershwin, the 20th-century composer who wrote, along with the title piece “An American in Paris,” some of the best-remembered symphonic works of the 1920s and 30s, namely 1925’s “Rhapsody in Blue” and the 1935 opera “Porgy and Bess.”

Oscar Levant was Gershwin’s biggest fan and his best friend. That’s why he’s in this movie. It’s 1951, and Gershwin has been dead for over 10 years. And here’s his friend, looking like a total mess in Technicolor, making sure that Gershwin’s legacy stays intact.

At least, that seems to be the reason. With Levant, one never knows.

I fell in love with Levant because I fell in love with Gershwin: for a time, the two were inseparable, not just as people, but as concepts. At 16, I was reading and learning about Gershwin, the person whose music spoke to me the most at that time. While everybody else was embracing the emo strains of My Chemical Romance or the hipster pop ballads of Weezer, I was–shamefully–burying myself in the early 20th century, reading first-hand accounts of how, at Aeolian Hall in 1924, audience members fed up with a Paul Whiteman program of jazz compositions were headed for the door and stopped in their tracks, instantly reversing direction at the first wailing glissando of the “Rhapsody.” It was a monumental moment in music, and I was interested in moments more than anything else.

Oscar Levant’s life was a different kind of moment: a long, tortured one, stretching headlong into oblivion after his best friend’s death from a brain tumor in 1937, at the age of 39.

“In the six months preceding [Gershwin’s] death,” Levant wrote in his first book, A Smattering of Ignorance, “life for him was just one big, wild, marvelous dream come true.” The dream quickly turned into a nightmare in those final months, with Gershwin taking on OCD symptoms that Levant himself would mirror throughout his later life. In the same essay, Levant recalls how Gershwin, shortly after being diagnosed with the tumor, developed the habit of “call[ing] the names of streets as he passed them. If he missed one, he’d make his driver go back.”

Levant’s relationship with his friend was fraught, to say the least. Though Levant expressed love and loyalty to Gershwin, it was hardly returned. Gershwin seemed to view his friend as inferior, almost a hanger-on despite Levant’s own sizable accomplishments in composition, explaining on one train ride when they had to sleep in adjoining berths: “upper bunk and lower bunk: that’s the difference between talent and genius.”

It was clear that he viewed himself as the genius.

Yet Levant continued following his friend and interpreting his work, playing Gershwin music “until it exuded from [his] body like an excretion of a drug.” In 1937, because of the stress caused by playing a Gershwin memorial concert, he began taking sleeping pills. Other pills followed.

And yet, after Gershwin’s death, he still managed to put together some semblance of a career, even if it was more like a living memorial to his dead friend. Whether in musicals like An American in Paris or the Gershwin biopic Rhapsody in Blue (1946) that outwardly celebrate Gershwin or in Gershwin-adjacent music-centered films like Humoresque or The Bandwagon, he could be seen as a weird, yet unforgettable presence, a kind of blister on film. His hurt over his friend’s death hadn’t gone away, and in so many film appearances it feels like he’s there to bear witness. To pay homage. To make sure that nobody takes too many liberties. To interpret.

In these movies, he usually appears as himself, or as a kind of comic non sequitur in the piece, adlibbing his lines to the point of making everyone uncomfortable. While filming 1953’s The Bandwagon, he was recovering from a recent heart attack and looks like he’s just on the verge of having another: which might explain why he artfully dips out of frame for most of the ensemble dance numbers in the film. The joke in that film–as in most Levant appearances–is that he’s a hypochondriac. But he wasn’t. There were so many things wrong, it was just that nobody understood what they were. So they chalked it up to quirkiness, failure, and inability to even want to succeed.

It was my fascination with Levant as a fringe figure that lead me to his book, and it was the book that gave me a primary inkling of things in me that perhaps hadn’t been addressed as they should have been in my own life. These things were not hypochondria, OCD, pill addiction, or amnesia per se, but bore a fierce resemblance, in the silence surrounding them, to the way the former conditions were discussed in Levant’s time. The mystery of Levant’s relationship to mental health and its seeming symbiosis with his emotional life reflected on a similar kind of internal mystery of my own, as I saw it.

I almost went to a child psychologist at age 8, when I started to have panic attacks. Ultimately I didn’t, but I probably should have. What happened was not that I stopped having the attacks or stopped fearing death by choking, death by sleeping, or death by leaving the house. It was that I learned to mask these fears, appearing as if they had been resolved. I would go to sleepovers at my friends’ houses and wake up in the middle of the night, terrified of dying. My heart was beating so hard it felt like it was going to bust through my sleeping bag and run back home. I don’t know how I got through it, but I did. What was I supposed to say, “I can’t sleep over your house anymore because I’m having panic attacks?” I didn’t know what panic attacks were. I simply had them, daily, multiple times a day, and kept them to myself.

The most important similarity of all was that neither of us knew the language we needed in order to describe ourselves. In both cases, there was only the sparest vocabulary available for a group of tendencies that didn’t seem to have any connecting thread, and this vocabulary was predominantly clinical. And a lack of language for something creates—as I’m sure everyone knows—a silence around it.

OCD presents itself as a code that can’t be cracked by anyone outside of the person it affects because its logic is personal, deeply internal, and incommunicable. He had a sort of script inside of him that told him what streets to avoid, what omens were good and which were bad. The things his brain told him were true could not be told to others without being used against him, and the more the illness developed, the more his credibility was lost. When he tells his psychiatrist about his anger at his wife for touching objects in the home that he considers “holy,” the doctor’s response is: “You can’t blame your wife for behaving normally.” In a period of psychoanalysis that had not developed the sensitivity required to eschew the category of “normal” altogether, a person like Levant was doomed. He had transitioned into the realm of the abnormal and his illness, by the strict gender mandates of the time, feminized him. His gender was “patient.”

“Rituals have taken the place of religion for me,” he says in Amnesiac of the last phase of his life. He wrote the memoir when he was 59 and died six years later. In this book, these rituals and obsessions are explained in depth. He was once given a lemon as the prize at a dance competition for doing the worst waltz; he couldn’t have lemons in his presence afterward. He spilled beet juice on a white tablecloth once: no more beets. He felt competitive with King Oscar sardines because they shared his name, and wouldn’t allow them in his house. A stray Butterfinger wrapper on the street would be enough to make him change direction.

“My rituals are automatic,” he says, “mechanical and absolutely necessary, and I perform them without thinking…

“When I button my shirt, for example, I always button the lowest button first. When I take off my shirt, I do it from the top down. When I turn on water faucets the first time, I tap each faucet with both hands eight times before I draw the water. After I’ve finished, I tap each of them again eight times. I also recite a silent prayer. It goes ‘Good luck, bad luck, good luck. Romain Gary, Christopher Isherwood and Krishna Menon.’ I also tap my clothes.”

He writes in Amnesiac about the time when he was reduced to “complete infantilism” after being served tapioca pudding at one of the many institutions where he was placed in the 50s.

“A wild glint came into my eyes and in the presence of my wife and children I shrieked at the top of my voice, “I love this more than anything in the world!” I had to be withdrawn from tapioca pudding slowly.”

A man known for shooting his mouth off in unpredictable ways was being given constant opportunities to embarrass himself in the public eye, both by the powers that be anxious to monetize his weirdness and by his own social group.

Levant had plenty of friends–including all of the Marx Brothers and members of the Algonquin Round Table who loved him for his bizarre wit–but the minute his quirkiness started to descend into mental illness, they had no idea what to do with him. Except, you know, laugh. “Singin’ in the Rain” composer Adolph Green recalled that “no one ever felt quite secure with him,” as if Levant’s performance art style of being could at any moment make the transition from charming to manic. It could, and it did. Toward the end of Levant’s life, when his manias had taken over, Green recalled visiting him at Mount Sinai and “mentally pinch[ing] myself as I sat there with Oscar urging me to keep under my hat a piece of 1867 gossip about Turgenev and his group in Paris.”

His other friends were just as happy to see their friend as a kind of fake person, in the words of S.N. Behrman, “a character who, if he did not exist, could not be imagined.” The novelist Christopher Isherwood, who developed a friendship with Levant later in life, thought him a Dostoyevsky character come to life. Some were less charitable: Joan Crawford professed disdain for Levant after he asked her—noticing her extreme penchant for knitting on the set of 1946’s Humoresque—“do you knit while you fuck?” And Joseph Kennedy called Levant—to his face—”one of the few Jews I like.”

But perhaps no friend was at once as caring and as inconsiderate as the late-night talk show host Jack Paar, who would invite Levant on to talk about his manias and phobias for a scandalized audience who took it as comedy. Before introducing his guest, he would warn viewers that “for every pearl that comes out of Oscar’s mouth, a pill goes in.”

The pills were a result of doctors not really knowing what was going on with him. First, a doctor prescribed Nembutal for sleep. He became addicted to that, then to morphine, then to Dexedrine.

After Levant was hospitalized and too ill to appear on the show anymore, Paar would often sign off with: “goodnight Oscar Levant, wherever you are.”

Where he was, usually, was in some institution where nobody knew what to do with him. He had the wherewithal to write about it, at least, but outside of that, nobody seemed to understand what to do about it or how to contextualize it. Least of all Levant himself.

If the content of Amnesiac was comical, the actual context was not. And these events, more often than not, were feelings, retold in a comic context without having originated out of one. This is basically the definition of camp: laughing when you probably should be crying because it’s just all so tragic that it’s managed to flip over into absurdity. There was a similar grasping in Levant that I felt in myself. He seemed not to know how to describe himself, and there is an echo of this throughout his writing. He once referred to himself as having been “still alive when Wilson was President” and later answered Noel Coward’s claim that all Americans are neurotic with: “But I’m not an American!” (He was.) There is a feeling, toward the end of his life, of his losing a sense of what words mean—or at least acknowledging them to have a personal sense that is different from the general, accepted sense. I did this, too. Once you realize that the clinical categories of sex and gender are lies, you wonder what other things are lies, too. Things you’re told about as fact that aren’t facts at all. What if anything is possible? The thought is enough to make you go mad, and go mad I did, at several different points, just trying to square my sense of the world with everybody else’s.

I have to confess that I’ve been trying to write this story for over 15 years. Not just because the story is twisty and tangled (though it is) or because for so long, I couldn’t understand what the story was in regards to myself. Why it was that I loved this man so much. But I instantly understood, at 16, that he was me. That as much as I’d like to see myself as a Gershwin type, a sunny talent who “pisses melody” and dies in a blaze of glory, I’m not him. I’m the other guy. I’m the ugly-faced man in the corner trembling from withdrawal, trying to get his mind to stay quiet long enough for him to enjoy an outing with his friends, or a family dinner. I’m the freak who lives in the margins trying to figure out what’s true and what’s false, and what ways my brain is lying to me, and in what ways it’s telling the truth. Maybe my brain has always told me the truth, and that’s what’s been making me crazy all these years. Just the knowledge that personal truth can be so opposed to the reality everyone else lives in is maddening enough to make you forget your own name. It’s the kind of societal gaslighting that, for so many of us, never quite goes away. The thing that tells you it’s your fault for not being able to shut up and get in line, or that it’s your fault that you can’t just enjoy the party, or that it’s your fault that you can’t love someone without becoming totally obsessed with them.

Oscar Levant was the first true passion of my life. He was me, and by that I mean that he was as close to a historical trans person as anyone I’d ever learned about. And history, I felt, had kept him from me.

It’s still keeping him from us.