The last of four light standards was raised just after 4 p.m. for a party at Medinet Habu, the mortuary temple of Ramses III on the Nile’s western bank. Round tables, covered in black linen, would later bear sets of glasses and silver flatware. Chicken, cooked at one of the hotels, arrived later, along with the American and Canadian tourists paying for the privilege of eating it in this rare and ancient religious site. There would be no dancing or drinking, and only soft, tasteful music – harps, perhaps.

I’ve been teaching political theory in Cairo for a few years now, and I learned of the controversial aspects of these parties from the independent newspaper Egyptian Streets, which prepared me for seeing them in action during my Easter break in Luxor.

I ran into Mahmoud, an official from the Ministry of Antiquities, who helps supervise these tourist events. The parties at Medinet Habu are weekly occurrences, he told me. More rarely, they’re also held at the more famous mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut, which is less accessible, and too narrow for throwing a decent party. The cramped layout of the temple worked to the advantage of Jamaat al-Islamiya during their bloody attack on tourists in the 1990s, but neither of us spoke of that.

The parties are good for antiquities, Mahmoud said. The government can make money, and advertise the antiquities, although the safety of the monuments always comes first; a bigger problem, he said, is local building, which encroaches on the sites.

The biggest problem he faces must be groundwater, I ventured—the same issue plaguing Islamic heritage sites in Cairo. But no. For him, the biggest problem is the pigeons. They destroy everything. Reflectors might distract them – but what of the shaded areas of the large complex? A pigeon tower was built to the southwest, but the pigeons avoid it. He has been considering iron spikes, he said, and I imagined the kind that deter skateboarders, but everywhere, metal teeth upraised against intruders from the sky.

The word “tomb” would ordinarily bring to mind Cairo’s necropolitan dust, and the political and social censorship in modern Egypt, but here in Luxor a tomb is a memorial, a “house of millions of years.” Near sunset, I walked west from the colossi of Memnon on Tamthal Mamnoon street, which runs parallel to the memorial temple of Amenhotep III, whose entrance pylon the colossi would have guarded. I had just eaten dinner. The restaurant, sitting on leased land within the ancient footprint of the temple, will eventually be levelled, and the temple reconstructed. The proprietor wasn’t too worried; he has another restaurant. As I walked off the meal, my path took me roughly parallel to the east-west axis of the New Kingdom tombs inscribed in the sloping hillside of Qarna.

Here is an older meaning of “west” than the everyday Manichaean oppositions of Egypt/US or Asia/Europe. The west here means the afterlife, the deathless Fields of Reeds, and the underworld through which the sun takes its night-journey back east – on the water above the firmament, or, in another version of the story, through the night-goddess’s body.

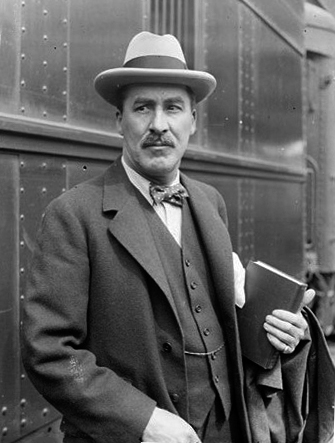

The legendary archaeologist Howard Carter (1874-1939) publicly revealed the tomb of Tutankhamun on November 4, 1922, after thirty years of study and six separate excavations. In the final excavation, he had cleared one of the ancient tomb-builder’s huts from the tomb of Ramesses VI, revealing a stone stair descending into the limestone; this in turn led to another door, with seals apparently intact. Through this final door Carter made a hole, and slipped an iron testing-rod through it to see whether there was a chamber beyond, or more debris that needed clearing. Widening the hole, he inserted a candle. At last he looked inside, and saw what he is said to have called, “wonderful things.”

public domain via Wikimedia Commons

public domain via Wikimedia CommonsBefore I left Cairo, an undergraduate student told me that his family home had been seized in order to rebuild the Avenue of the Sphinxes connecting the temples at Luxor and Karnak for the hordes of eager tourists. His family members were beaten, and their possessions bulldozed along with their home. A living present, sacrificed in order to conserve the past.

The tourist and traveler are not excavators, but what happens when we widen the aperture through which we see the the beginning and the end of life, of civilization? What happens when Egypt is used as a candle to illuminate the desire to build, to discover, or to conserve?

Howard Carter worked with Flinders Petrie, excavator of Amarna. But it was a German, Ludwig Borchardt, who discovered the famous Nefertiti bust. The story goes that Borchardt duped the Frenchman inspecting finds, resulting in the export of the royal limestone bust to Germany, where it remains. Internationalists such as James Cuno argue that the bust should stay put, and Zahi Hawass and other nationalists argue that it must return home.

Why return this treasure, if modern Egypt shares no religion, language, culture, or form of government with its ancient civilization? Some argue that if anyone has a strong claim to be the bearers of ancient Egyptian culture, it would be the Coptic Christians. Their language has roots in hieroglyphics and Greek, using the alphabet of the latter, plus six Egyptian phonemes.

The millenia of graffiti – in Greek, Latin, Coptic, English, French, Arabic – inscribed on the various temples, or bursting forth from pharaohs’ lips like word-bubbles in comics, in the tombs, are a reminder that the religious cultures of Pharaonic, Coptic, and Muslim Egypt have neither the power nor the right to dispossess one another. Distinguished Egyptologist Salima Ikram makes a similar point when she offers Pharaonic art as a secular meeting-ground for religions that often compete together.

If the Nefertiti bust is to be returned by the Germans to Egypt in order that Egyptian museums may tell a more coherent story of Egyptian history, there is a case to be made for its return to the Upper Egyptian city of Amarna rather than to the Amarna room of the Egyptian Museum or to the new Grand Egyptian Museum. The Amarna period is best understood in terms of the brief, massive gamble that Akhenaten took in moving the royal cult here, having radically transformed its locus of worship, from the gods of ancient Egypt to worship of the sun disc.

Taken as a whole, Egypt itself – village and city, pyramid and tomb – is also a kind of gamble, and one that raises a crucial question about intergenerational justice. Who gets to build a holy site? Who is born into what birthright? Whose tomb, whose house, whose place of worship is moved or destroyed? Which images and artifacts are returned to Egypt, and which become the mascots for another people?

Egypt, a nation of more than 100 million, with an annual population growth of 2%, is building a massive new high-rise city on the North Coast intended to house three million people. It is shifting to a new administrative capital even further east of Cairo, “the monster.” It is relocating the center of Egyptology from Tahrir Square to the Giza Plateau, a move funded by Japanese loans totaling USD $800 million. The government is cracking down on terrorism and on journalists, students, activists, and intellectuals as vigorously as it reaches upwards and outwards into the desert.

Revivalists and nationalists defend these quasi-pharaonic ambitions, painting Sisi as a modern-day Khaemwaset, the 20th dynasty son of Ramesses II and “first Egyptologist” with a taste for the study and conservation of the monuments of ancient Egypt. In this reading, Sisi will bring the newly reborn Egyptian civilization-state to its proper place alongside the similar civilization-states of Russia, India, and China. He is the pharaonic protector of maat (justice).

Alternatively, urban expansion may entomb the least well-off, while tourist sites, gated communities and desert suburbs become the exclusive domains of the rich, as in Dubai. Dubai can afford these optimistic expansion plans – in theory, at least – but Egypt cannot afford “dubaification.” (In practice, while Dubai’s poverty headcount is roughly 0%, according to World Bank statistics, this conveniently omits the fact that guest workers are providing massive amounts of cheap and precarious manual labor there.) Around Cairo, meanwhile, 750,000 desert city housing units remain vacant, even as the government adds one million units still farther outside the city. Egypt is also currently involved in a quarrel with its neighbors over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the filling of its reservoir. Not only have Egypt’s improvement projects ignored the ambitions of neighboring states to maximize the use of their own resources, denying them their own post-colonial development, it’s also radically unclear whether Egypt is on “the path of construction and humanity” that its president promises.

It is hard to imagine a pharaoh as a man, and a young one, but Akhenaten died in his early thirties. His religion and his capital died soon afterwards. His was the project of a lifetime, not eternity. His son, Tutankhamun, died before reaching the age of twenty.

Despite constitutional amendments made in 2019 to Article 140, which had imposed shorter limits on the Egyptian presidency, Egypt’s current regime, too, will end.

The Coptic Christian Church of the Holy Virgin in northern Minya governorate, built in 328 AD, is currently closed as it undergoes conservation by the Antiquities ministry, though it’s possible to request a visit. There’s a new hotel joined to the contemporary church, facing westward over the Nile, and I stayed there during a working holiday earlier this academic year. The church is located in a gated Christian community. Wandering in the village as a break from reading and writing on my first post-Covid trip outside of Cairo, my mandated police escort and I visited homes, mounted stone and wood balconies, and climbed on newly plastered roofs that shook and flexed with our passing. I wonder what will happen to the families we met. Nearby Samalut has been the site of clashes between police, Christians, and Muslims over the building of new churches there. Conserving the historic church above the gloriously verdant flood plain will not solve these problems, and it may create new ones – pilgrims, tourists, development, changes filled with hopes and fears.

According to the old stories, there is meaning even in the end of all things. The god Atum, the self-created god who emerged from pre-chronological chaos (nun), will become one with Osiris, lord of the dead, and the world will meld again with the undifferentiated primordial water. Until then, as always, we build meaning, and conserve the meanings built by others, as best we can, between the desert land and the fertile strip in which life flourishes.

Addendum: While I was editing this article I was informed of the death of one of my current students, Ali Saeed Ahmed Al-Batati, an international student from Yemen. I find myself unwittingly and unwillingly writing in his memory, and I dedicate these reflections to him.