[Author’s note: Speakers’ names have been changed to protect their privacy.]

Many Nigerian undergraduates are eager to return to school, awaiting with bated breath the end of the strike by the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU). I am not one of them. Every time news of the strike appears in my feeds, my heart feels like it’s in my throat.

Since 2016 the Abuja-Kaduna expressway has become a hotbed for abductions, with armed bandits attacking travellers and holding them for ransom. This year alone about 52 abductions have been reported, so anxiety grips anyone who needs to travel that road. Students at varsities in Kaduna State, like me, routinely travel the expressway at least three times a year, to attend school and return home for breaks.

When I moved to Zaria for school, such abductions were relatively rare; perhaps once in four months. I don’t remember the roads being so unsafe that I couldn’t travel to write my entrance exams in 2017, or resume school in January 2018. Attacks had grown a little more frequent by then, but my father and I were not yet aware of this.

The last time I travelled on the expressway was on a frigid harmattan morning in March of 2019. I got a message that there elections were being held in Kaduna, and my father rushed me to get ready in time so I could reach Kaduna before any election violence might erupt. We left the house at about 6:00 pm. it was dark, and I kept staring at the sky, looking for traces of stars. I was excited, as I always used to be when I was about to go on a road trip. If I’d known then that that road trip to Zaria would be my last, I would have taken more pictures.

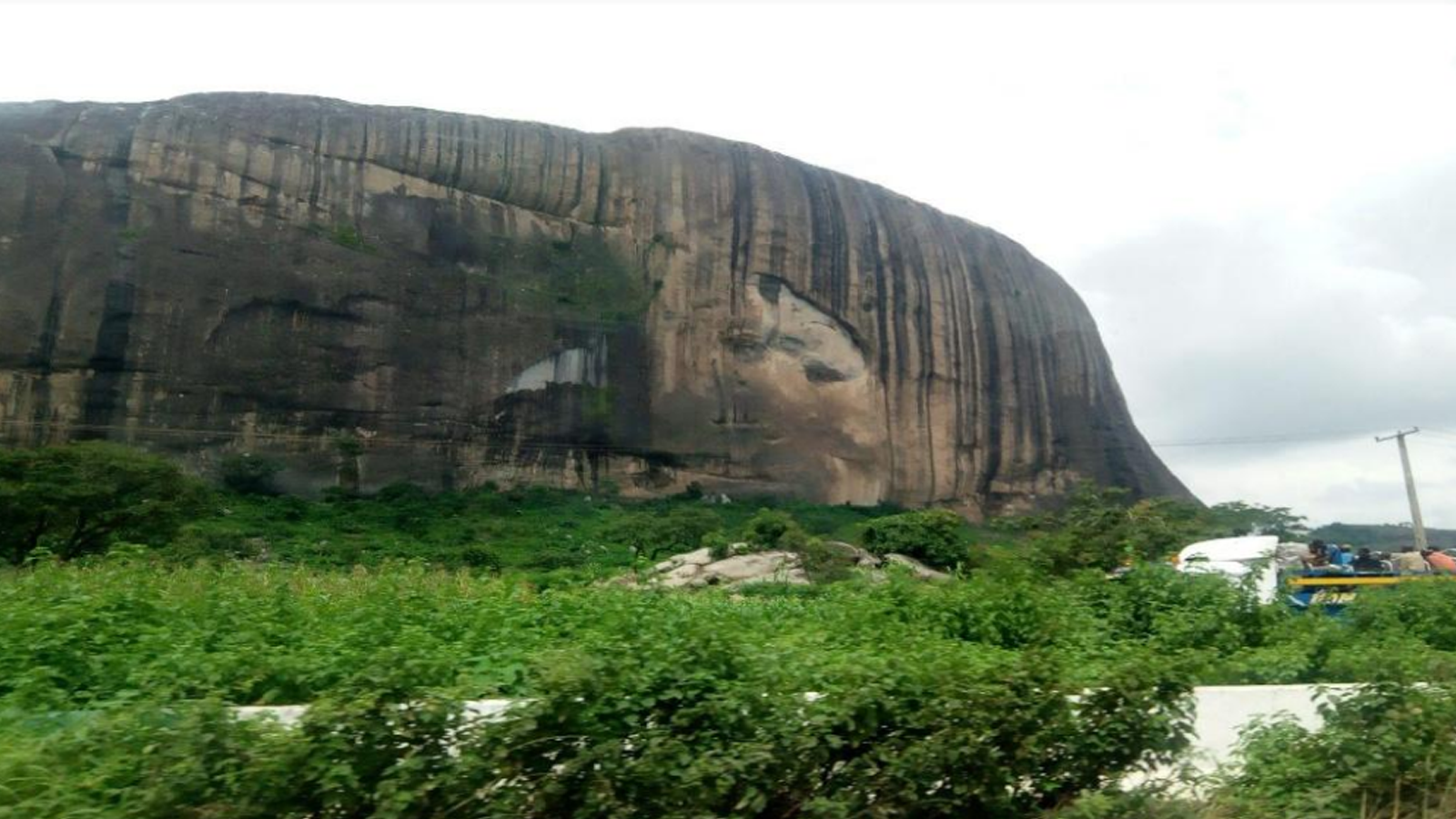

On August 24th, Google sent me a memory: a photo of Zuma Rock I’d taken on my Infinix Hot 5 phone on my way back from school after writing my final exams for the 100 level. The picture was dated August 17th, 2018, reminding me that it’s been more than four years since I last saw Zuma Rock, a hill on the outskirts of Abuja. Four years since I travelled by road to school.

I stopped travelling by road in 2019, when three students from the Faculty of Law of my school were kidnapped on their way to Abuja to solicit funds for their final year dinner. They were my seniors. I was in my hostel when I read the news on my phone. I was terrified; the possibility of getting kidnapped while travelling home began to materialise in my head; I envisioned myself in a forest, tied up with other passengers.

When it was time to return home after my first semester exams, my father told me to take the train from Rigasa to Kubwa.

My friend Najah and I got ready to take an extraordinary journey. One of our classmates, Gumel, asked that we share a taxi from Zaria to Rigasa to reduce the cost. So the following week, with Dave and Burna Boy’s “Location” playing through my headphones, I, Najah, Najah’s cousin and Gumel embarked on the journey from Zaria to Rigasa. At 9pm we boarded the train to Kubwa.

I spoke with several other students who, like us, had opted for the train. Fredrich’s* mother had heard that bandits were kidnapping people on the road as early as 2017, and told him not to come home; eventually he’d taken a bus to Kaduna, stopped at Kawo and took a tricycle to the train station in Rigasa.

When she gained admission into ABU, Zaria’s faculty of law, Khairat switched to travelling by train. Three students from her school had been abducted; they were held for about two weeks and were released and in one account rescued by the police,

“I hate the train,” Zainab told me. “It’s slow, and sometimes it can just break down in the middle of nowhere.’’ I’ve experienced these random breakdowns too, once getting stuck in the middle of a thick forest for 20 minutes before the train started moving again.

Despite the inconveniences, the train still seemed the safest means of transportation. So when there was an attack on a train bound for Kaduna from Abuja on the 28th of March this year, many of us were devastated.

“When I heard the train was attacked, I felt like the world had come to an end,’’ Friedrich said. “I’d already heard about scattered incidents of violence on the train, but never anything on this scale.” Of the more than 60 victims abducted from the train on March 28th, 23 people whose families can’t afford the ransom were still being held by the bandits five months later.

The attack in March left 8 dead, 41 wounded, and some kidnapped; today, about 200 victims are still in the captivity of bandits.

It’s said that different groups of bandits bid for custody of kidnap victims. I’ve also heard of people having to move out of their own homes, because of bandits operating freely nearby. The government has promised action, but to my knowledge, no kidnapped victims are reported to have been rescued by policemen or the military.

The only other option is to take a flight to Kano and a car to Zaria,or take a flight to Kaduna and risk getting kidnapped along the airport road.

“I succumb to taking flights now,” Gumel told me. But the aviation sector is also facing trouble because of the scarcity of Jet A-1 aviation fuel. People are frequently left stranded at airports, yet they cannot travel on the unsafe roads.

Some students have been brave enough to continue travelling by road, despite the increase in danger. “Anything can happen to a person even when they’re at home,” said Becki; she has faith that God will protect her as she travels the road. I don’t share Becki’s certainty. The fact is, we’re left without a safe and cheap means of getting to school and back.

“I’m emotionally downcast,” Friedrich says. “I’m actually terrified ASUU might want to call off the strike.”