THIS POST COMES TO POPULA FROM TASTEFUL RUDE,

A FELLOW MEMBER OF THE BRICK HOUSE COOPERATIVE.

“It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, 6, or 7 to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you”.

-James Baldwin, from “The American Dream and The American Negro,” 1965

IN A PHOTO album there exists a grainy picture, its corners rounded. A pinkish hue suffuses the image: an expanse of blacktop with rows of chairs occupied by seated adults. I stand before them. It’s my kindergarten graduation. I wear a long dress, the kind my mother and grandmother favored, my short brown hair in barrettes. A rosy tint appears to emanate from the dress, suffusing the atmosphere.

With my right hand over my heart, I’m leading the Pledge of Allegiance.

Taken with a Kodak Instamatic, the picture looks soft and fuzzy, lacking the sharpness of contemporary photos. Most distinct is that my child self was executing a common, expected recital, leading an audience of compliant adults in ritual. I hardly understood the words I recited and had no idea of their origin.

Why was I chosen to lead the Pledge of Allegiance?

My heart demands an answer to this question.

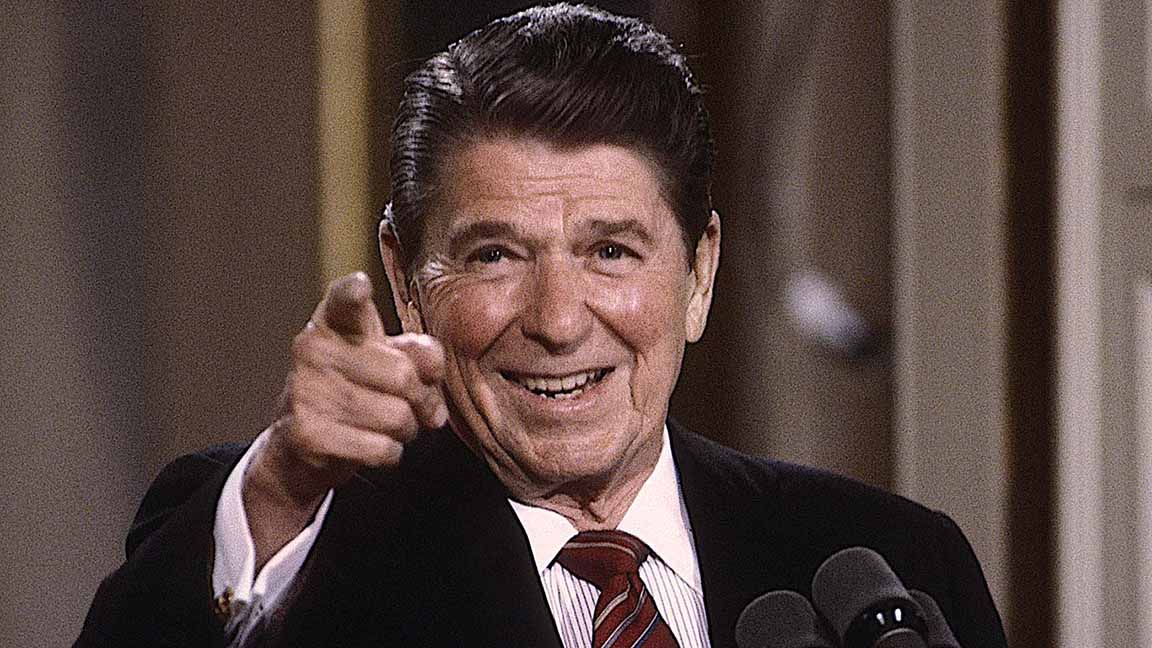

I open a web browser and search for archival footage of the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan. This attempt happened two years after my kindergarten graduation photo was taken.

My search yields several articles from the Reagan Library, a place I’ll never set foot in. It’s in Simi Valley, just one county away. I associate Simi Valley with one date I had, aged sixteen, with a man more than twice my age who, at the end of a night spent eating seafood and drinking cocktails by the ocean, found himself unable to go beyond kissing his underaged “date.” In his house in Simi Valley, he told me he could not see me again, and while at the time I was confused—our date having occurred after weeks of open flirtation—I have often thought back on this man’s sudden burst of conscience.

Footage of Reagan and his Secret Service exiting the Washington Hilton plays on screen. The President, a former actor, waves, his entire body performing confidence until his smile is extinguished. Bystanders surrounding Reagan respond with an uncanny choreography, nearly balletic. Reagan is pushed to the ground. Cameras aim at the area where the gunman must’ve been standing, where there is now a huddle of men swarming the assailant. More guns and more chaos follow.

The political science books I’ve read this year foretell a second civil war, a situation already in gestation. Some of the most damaging policies that came out of the last presidency are maximal versions of Reagan policy. I think often about how we discuss presidents, politics, and power in my house, how my eleven-year-old is synthesizing what she hears from us, her parents, versus what she hears and takes in from school and the rest of her world. Remembering that my second-grade teacher was, in essence, a propagator of unquestioning allegiance to the president and how she indoctrinated our class keeps me wary of and alert to what my child is learning at school. In 1981, my second-grade teacher, Mrs. Pelka, confused me. Why did she love the president when others were so angry at him?

It was around that time, second grade, that I first considered no longer pledging allegiance to the flag. It was also the first time that I wondered if my teacher, and maybe other adults, might be wrong.

The day after the assassination attempt, our second-grade class president waved once, twice, and fell to the ground, convulsing for effect. Mrs. Pelka had witnessed the simulation and scolded her. This is not a joke, this shooting. This is serious, her tone and words conveyed. Meanwhile, my friend Abigail had told me that she wished she could kick the president while wearing her mother’s wooden clogs.

One day, Mrs Pelka brought a roll of butcher paper into the classroom. I can’t remember if it was before or after the assassination attempt. She unfurled the white onto a long row of our pushed-together desks with great ceremony. She spread out aluminum trays, laid out paint brushes. Tempera scented the air. Each student was to place their hands in an aluminum pie tin of red, white, or blue paint, then press our palms onto the clean sheet. Our handprints, our singular whorls and lines, dried overnight in the dark classroom.

Mrs. Pelka wrote large on the banner in her neat, fat cursive either Happy Birthday or Get Well Soon. Reagan’s birthday was in February, and the attempt on his life was in March. Mrs. Pelka wrote the name of our school, and our class, Room 12. Once it dried, she rolled the banner up and mailed it to the White House along with a jar of jellybeans. The president had taken up jellybeans to help him quit smoking. His inauguration had featured three and a half tons of them.

When we received a reply from the White House, Mrs. Pelka read it aloud. The President thanked us. He said he couldn’t accept our gift of jellybeans, just to be on the safe side. Mrs. Pelka held out the letter to show the class. The president’s signature gave the letter a strange power.

I thought a lot about Abigail and her desire to use her mother’s wooden shoes to injure the president. Television news reminded me of the power of the president. My teacher believed in him, and I understood that she wanted us to believe in him too. Her intentions felt as rote as the Pledge of Allegiance. Hand over heart, we stood every morning and faced the flag in our classroom, where it was suspended high off the ground. A kid had once told me that if the flag touched the ground, liberty would pour out. I always imagined that if its corner so much as brushed the floor a mass of tiny people led by the Statue of Liberty would materialize and march out of the magic fabric. The fantasy was both chilling and electrifying and I sometimes watched and waited for the flag to drop.

In a small research study, people were found to perceive those who put their hand over the heart, even when they say something erroneous, as more credible. In essence, the study found that “people’s level of honesty can be manipulated through the unobtrusive performance of the hand-over-heart gesture.” The heart is the center of this action, a hand covering it meant to be a signal of pure, genuine intentions.

My heart’s intentions can’t easily be discerned. Because it is a renegade, I am forced to think of my heart often. The clinical diagnosis is atrial fibrillation. It chooses its own beat, and not metaphorically. There have been many times when I put my hand over my heart and, in its condition, I’m reminded of its rebelliousness. But for many years prior I have purposely not put my hand over my heart, foregoing this gesture I was taught in preschool. The little girl in the kindergarten graduation photo has evolved into something different, maybe unrecognizable to her, and certainly her parents, one of them gone, one still alive well into her eighties. The little girl’s heart went on to beat in a rhythm all its own, as later EKGs would show.

My first small tastes of rebellion arrived during sixth grade, though I quickly corrected my behavior, righting the compliance boat to keep on sailing. To be good was to follow the rules, and in my few years of Girl Scouts my sash filled with badges for all the time I spent, mostly alone, working for them. I did homework on my own without being reminded.

In ninth grade, something shifted for me, and I slowly, then swiftly, rebelled. When my mouth didn’t move for the Pledge of Allegiance, my teacher, an older white man, silver-haired and mustached, glared at me with his watery blue eyes. I sensed a hint of contempt meant to make me comply. Back then, not reciting the Pledge of Allegiance seemed like a minor dare on a weekday. No one asked me about it or called me out. By then I had already practiced not standing during Mass; I wasn’t Catholic, I reasoned, and since I was one of hundreds in the auditorium, I was never singled out. I’d had to ask my father how to say the Hail Mary. To my ears it was a short melodic litany that ran words swiftly into each other in a cadence I internalized… but the words? I watched my atheist father tilt his head, think for a moment, then start to recite, pausing, remembering, fumbling, until the prosody unspooled from his memory. I respected that my father had lost his faith, had forgotten a routine communication with God. What I’ll never know is exactly how my father’s atheism formed, and whether his straying from Catholicism was something he perceived as a revolutionary act.

Before now I hadn’t known why we performed the pledge. I only knew that it was suspect, that I was being asked to swear an oath to a country that, by the time I was in high school, I understood was astoundingly hypocritical and disturbingly inequitable.

Writing for Smithsonian, Amy Crawford traces the xenophobic history of the Pledge of Allegiance. The oath, which was authored by a bigoted Baptist minister, debuted in American classrooms on October 21, 1892. While patriots treat its words as gospel, the Pledge was introduced as a marketing gimmick not dissimilar from the prize in a Cracker Jack box. Companion, a popular children’s magazine, used the promise of free flags to boost subscriptions, and to celebrate the “arrival” of Christopher Columbus in North America, these flags would be raised. Loyalty would be promised.

The Pledge would see various drafts. During the Cold War, the words “under God,” were added to differentiate blessed Americans from those living in “atheistic Marxist-Leninist nations.”

My father, a Mexican American born in Torrance, California, was eleven years old when the right hand over the heart was made part of the Pledge ritual. He was living in central California and spent part of his youth picking grapes and cotton. That year my mother, a Mexican American born in East Los Angeles, California, would have been five years old. She lived with her mother and brother in a rented storefront in East Los Angeles. While I’m unaware of just how much of a role God or Catholicism played in my father’s early life, I know that my mother was part of a family of ex-Catholics who practiced under a Pentecostal umbrella before straying into an amorphous and churchless Christianity.

My father may have been in the Army in 1954, the year that “under God” became part of the pledge. That same year my mother would have been seventeen, cycling somewhere between one of the four high schools she was relegated to by my grandmother. She did everything in her power to keep her daughter away from the clutches of sin in the form of young men: evidence that in her youth, my mother revolted.

Some of the early protests against the Pledge of Allegiance were prompted by a concern that the pledge was a form of idolatry. Such was the case in 1940, when Jehovah’s Witnesses challenged recitation requirements for people of all ages.

They lost.

My own resistance is slightly more aligned with the 2004 11th Circuit Court of Appeals decision in Holloman ex rel. Holloman v. Harland. Holloman, a student who “silently rais[ed] his fist during the daily flag salute instead of reciting the Pledge of Allegiance with the rest of his class,” sued his high school economics and government teacher, the school principal, and the school board when he was punished for the gesture. The day before, May 16, 2000, another student, Hutto, had “remained silent with his hands in his pockets without causing a disturbance. When…asked…why he was not participating in the flag salute, Hutto responded that he ‘didn’t want to say it, he didn’t have to say it, and he hadn’t said it for a month.’”

It is satisfying to imagine a high school student uttering the words, I don’t want to say it, I don’t have to say it, and I haven’t said it for a month. Many of us can relate.

Mrs. Pelka taught me an important lesson, one that she didn’t intend to convey. My teacher respected a president who would enact policies that reduced wages, increased poverty, and decimated federal aid for basic public services. It was Reagan’s administration that marked the beginnings of what author and professor of politics Peter Dreier calls “the rise of a well-oiled corporate-funded conservative propaganda machine.” That machine is a given today, and has devolved further into one of harmful disinformation and misinformation. Mrs. Pelka, with her unquestioning veneration of power, unknowingly seeded in me an inclination to question authority and the uses of power.

The fortieth president is often described as having “paved the way” for the forty-fifth president. There is a wellspring of articles comparing the two presidents and their legacies. “Let’s Make America Great Again” on Reagan’s campaign posters in 1980 was slightly altered to create Trump’s 2016 “Make America Great Again” and the cascade of profit-generating merchandise associated with it. Today you can buy online for $174.95 a United States flag, “a beautiful and impressive keepsake…flown over the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California.” Consumers can also request to have their flag flown over the library to memorialize “birthdays, anniversaries, or any other special days.” If you search “Trump” and “American flag” you’ll likely come across the bizarre, but telling, image of Trump with his arms wrapped around an American flag after having kissed it, a smirk on his face.

For most of my life I’ve felt that I could not in good faith perform the Pledge of Allegiance. I do put my hand over my heart with other intentions: first and foremost to notice or study the cadence of my heartbeat. A yoga instructor in a video or a meditation teacher on an app encourages placing a hand over the heart and sometimes I follow. The action is also a gesture indicating I am overwhelmed whether by joy or sorrow.

I still struggle with the idea of “pledging allegiance” to anything. I’m wary that pledging my allegiance means I’m giving up something, a sense of freedom or autonomy, though when I think it through, there’s a certain freedom to be gained when I am most clear about where my allegiances lie.

I pledge allegiance to everything and to very little. I pledge allegiance to bent knees during the national anthem that I don’t stand up for. I pledge allegiance to not observing the Pledge of Allegiance. I pledge allegiance to people marching in the streets. I pledge allegiance to public refrigerators filled with free food. I pledge allegiance to those who live on the margins, whose humanity is often forgotten or ignored. I pledge allegiance to the ones who are willing to take risks so that others may live with dignity. I pledge allegiance to care and thoughtfulness, to empathy embodied in conscious actions.

Hand over heart I pledge allegiance to the soft but sure thump. Hand over heart I feel its vitality, my life force under the palm of my hand. This may be the clearest compliant act I can manifest now: I pledge allegiance to the flow of blood snaking through my body, the rhythm and beat, as it courses and flows through my noncompliant heart.

Wendy C. Ortiz is the author of three books. She was awarded a Tin House residency in 2022 to continue working on her next book, of which this essay is an excerpt. Wendy lives in Los Angeles.