THIS POST COMES TO POPULA FROM TASTEFUL RUDE,

A FELLOW MEMBER OF THE BRICK HOUSE COOPERATIVE.

I AM NOT the great-great-great granddaughter of an Aztec princess. In fact, it was my Chicano dad who made sure that neither my sister nor I ever spread such falsehoods, the reasons that he set us straight being as simple as they were complex. He’d seen Chicanas decide to self-indigenize and reach for Aztec crowns, spinning new identities out of myth. Our dad acted so that we wouldn’t repeat their hustle.

He wanted us grounded in our own difficult history.

He educated us about the iteration of mestizaje that had made us, telling us that we are descended from Spanish people who had colonized the lands that became the Mexican states of Jalisco and Zacatecas. He said that a lot of indigenous people defended these lands and that we, too, were the descendants of these original people. Jalisco and Zacatecas were part of a region referred to as La Gran Chichimeca, and some Chichimec communities, like the Wixáritari, continue to resist. Others were eradicated by genocide. Our dad also explained that we came from Africans brought to Mexico as enslaved people, and that these ancestors may have labored in mines or sugar fields. He told us that if we went around claiming to be Aztec royalty, we’d be as gross as one of my blonde classmates, a girl who strutted around the playground informing other kids that her great-great-great grandma was not just Cherokee but a bona fide princess.

I give these anecdotes as context. The history of every settler colonial state forged in the Americas is violently unique, but one wouldn’t know that after reading a recent op-ed published by the San Francisco Chronicle. The piece, an attempt to unmask activist Sacheen Cruz Littlefeather as a pretendian, was penned by Jacqueline Keeler, a writer with a documented history of questionable, hurtful, and outrageous behavior. She has advocated for the use of Black face in activism. She has accused First Nations people from Canada of stealing jobs from native people in the United States. She falsely accused Cheyenne politician Ben Nighthorse Campbell of being a pretendian.

My response to Keeler’s op-ed isn’t so much a defense of Littlefeather’s claims to indigenous identity as it is a critique of various insinuations that her sisters appear to make.

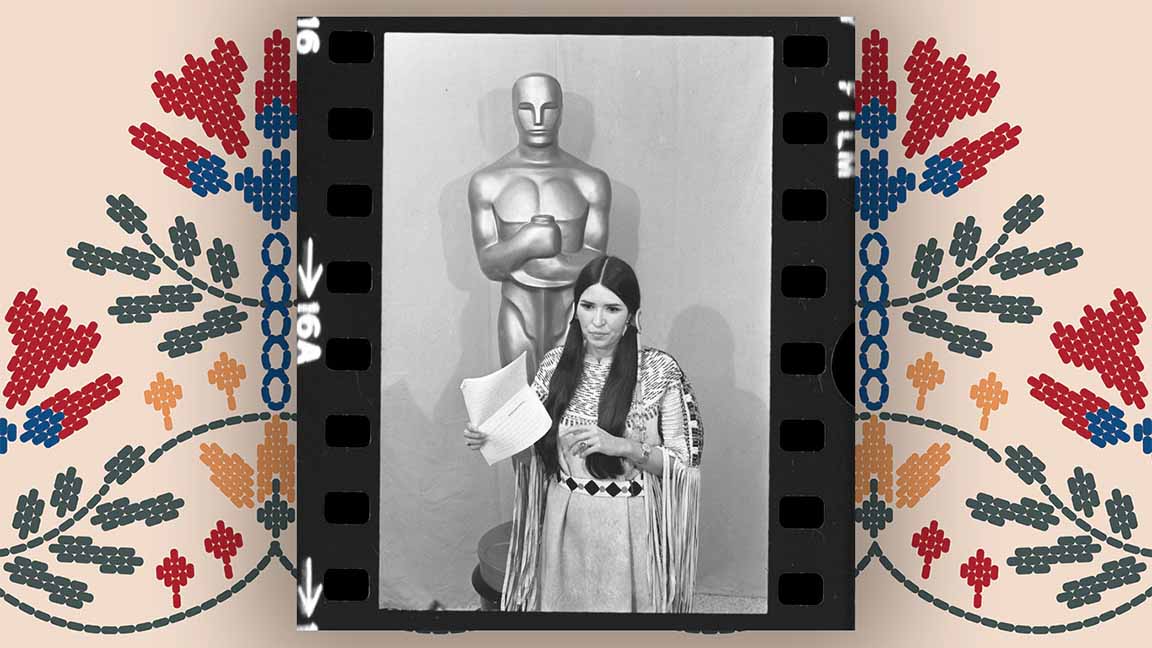

In 1973, Littlefeather became a household name when she delivered a speech at the 45th Academy Awards.

Hello. My name is Sacheen Littlefeather. I’m Apache and I am president of the National Native American Affirmative Image Committee. I’m representing Marlon Brando this evening and he has asked me to tell you in a very long speech, which I cannot share with you presently because of time but I will be glad to share with the press afterwards, that he very regretfully cannot accept this very generous award. And the reasons for this being are the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry – excuse me – and on television in movie reruns, and also with recent happenings at Wounded Knee. I beg at this time that I have not intruded upon this evening and that we will in the future, our hearts and our understandings will meet with love and generosity. Thank you on behalf of Marlon Brando.

Littlefeather, who also claimed Yaqui ancestry, died on October 2 in Novato, California. Twenty days later, Keeler published her take down. In the editorial, Keeler quotes the activist’s sisters, Rosalind Cruz and Trudy Orlandi. Cruz calls her sister “a fraud,” describing Littlefeather’s claims to indigeneity as “insulting” to her parents. This seems telling. A person might find it degrading for their parent to be described as indigenous because they are racist, because they want for their lineage to be perceived as European and solely as European.

Orlandi told Keeler that her sister’s story is “a lie.” She said that Littlefeather fabricated an “American Indian princess” story because, “I mean, you’re not gonna be a Mexican American princess.” To the best of my knowledge, Littlefeather never claimed to be royalty of any sort, but I can assure Orlandi that there are plenty of girls claiming to be princesses of one sort or another running around California. About their dad, Orlandi said, “My father was who he was. His family came from Mexico. [He] was born in Oxnard.” These comments seem to suggest that Mexican ancestry precluded her father, Manuel Ybarra Cruz, from having Apache or Yaqui ancestry. Her comments also seem to suggest that being born in Oxnard, California, precluded Ybarra Cruz from having Apache or Yaqui ancestry. The trouble with such an insinuation is that every Yaqui person I know is Mexican or Mexican American. More to the point, most indigenous people I’ve known have been Mexicans living along California’s Central Coast, the region where Oxnard is located.

California’s Central Coast stretches from Monterey Bay in the north to Point Mugu in the South. I was born on Chumash land in the Central Coast in the 1970s. During my childhood and adolescence, my hometown of Santa Maria was populated by many Mexican Americans and Mexicans. Some of these Mexicans were migrant laborers from the states of Oaxaca and Michoacán, and many were also indigenous people, Ñuu Savi, Binnizá, and Purépecha (Mixtec, Zapotec, and Tarasco).

According to the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, there are 16,933,283 indigenous people living in Mexico. That is 15 percent of Mexico’s population. Among the unrecognized indigenous people living in Mexico is the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé nation, also known as the Apache. N’dee/N’nee/Ndé communities exist in Chihuahua, Sonora, Durango, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas. Activists belonging to the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé nation continue to fight the Mexican government for formal recognition.

While there is one federally recognized Yaqui tribe in the United States, there are eight Yaqui pueblos in Mexico: Vicam, Loma de Guamúchil, Loma de Bácum, Tórim, Pótam, Ráhum, Huirivis and Belem. Most of these communities are in Sonora, but others exist in Chihuahua and Durango as well. In 2021, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador offered a public apology to the Yaqui pueblos, admitting that the Mexican state was responsible for centuries of abuse. Might Littlefeather have been a descendant of indigenous people? I can’t answer that question. I can say that for anyone to use Mexican ancestry, or birth in Oxnard, California, as evidence that someone didn’t descend from indigenous people is absurd. Such rhetoric smacks of xenophobia and racism, and it wouldn’t be the first time Mexican Americans have engaged in these bigotries. Have you heard Nury Martinez talk?

Myriam Gurba is the editor-in-chief of Tasteful Rude. She is also the author of the memoir Mean, a New York Times editors’ choice. O, the Oprah Magazine, ranked Mean as one of the best LGBTQ books of all time and Publishers’ Weekly describes Gurba as having a voice like no other. Her essays and criticism have appeared in the Paris Review, TIME.com, and the Believer. Gurba has been known to call shitty writers pendejas and has no qualms about it. Along with Roberto Lovato and David Bowles, she co-founded Dignidad Literaria, a grassroots literary organization that seeks to revolutionize publishing.