AROUND MOST CONSTRUCTION sites there’s a chain-link fence, and in the fence, at least one gate. Stepping through that gate is usually the best, sometimes the only, way a union organizer finds workers. Mornings, workers walk in from cars and pickups, bleary-eyed and angry at their commute. The most you can do is to offer a flier or booklet on the way in and hope they’re not too cowed by eyes around them to take it. Day’s end, they exit through the gate dog-tired but hurrying into an even uglier commute, often to distant exurbs or beyond. If a food truck stops outside for break or lunch, they scramble around each other to order, and hurry back in to eat and drink. No time, no time to talk.

Best, then, to approach the workers where they work.

I organized for Ironworkers Local 377–San Francisco from 1999 to 2002, during the dot-com boom. The local’s jurisdiction extends from Big Sur north through coastal counties to the Oregon line. My territory was everything north of Page Mill Road, just below Stanford University.

Many jobsites I found through the Dodge Reports, a commercial publication obtained for us by the California State Building and Construction Trades Council. Others I found by taking a different route every time I crossed the City or drove down and up the Peninsula, or even by standing atop the City’s Twin Peaks and looking for cranes.

Some, I couldn’t enter. Work in safety containment, such as for asbestos, is inaccessible, as is work in secured locations such as prisons and military facilities. The work of a raising gang, the Ironworker crew that chases the sky with steel, is a pas de cinq, sometimes six—two connectors, hook-on, tag-line, pusher, sometimes phones. The dance is always dangerous. Steel is moving, flown by crane or derrick. Though I never saw the dance as refined in non-union as in union work, in respect for the workers and their risks, I never cut in.

But I stepped through hundreds of gates. At almost every jobsite entry a sign instructs visitors to report to the job office. I ignored it. My business was not with the office, but with workers. Neither, though, did I hide; I entered as though I belonged, dressed as I had for the work myself: Hickory shirt, black twill trousers, Red Wing boots, brown duck Carhartt jacket. For better odds of blending in I did turn my hardhat bill forward as do other trades, not backward as does an Ironworker.

There was some physical risk, though I suffered no assault beyond being shoved backwards across a jobsite and out its gate. My counterpart south of Page Mill, though, was told that if he returned to one jobsite a rifle would await, trained on him from hillside oaks. Robbie Hunter, sturdy bantam who apprenticed to the trade in the shipyards of Belfast, stepped on behalf of Ironworkers Local 433–Los Angeles through a non-union jobsite gate in 2008 and exited battered up and down by a two-by-four. He, too, has tales of guns, some shown, and some pulled on him.

I came to ironwork in my late 20s. My wife and I had decided on a family, and we concluded we’d need a house—even then, almost unattainable in San Francisco. I had worked a succession of clerical jobs, winding up in a store that sold British clothing to conventioneering doctors and businessmen. It didn’t pay nearly enough to afford a house. There was a path to promotion, but I couldn’t stomach the thought of spending much of my working life cooing to the wealthy. I had no intention of returning to school, which would, again, have delayed a family.

I’d grown up among tradesmen on the south side of Bernal Heights, then still a blue-collar neighborhood in the City. I was tall, reasonably strong, liked being outdoors. I decided to find a trade. Neither the Plumbers nor the Electricians were taking apprenticeship signups for many months, but signups for the Ironworkers apprenticeship were open always, under a consent decree that had desegregated the union years before. I signed up and was placed on a waiting list.

I learned from an Ironworker who was dating the same woman as my father that I could bypass the list by obtaining from a steel contractor a “Letter of Subscription” promising me employment for a minimum of six weeks, barring major problems. A few days later, wearing work boots and work clothes and carrying my lunch in a paper bag, I walked around Downtown and the Financial District looking for construction that seemed to have more than six weeks of work left in it. At Pine and Market, I found the early floors of a high rise. I thought the manlift operator would know everyone on the job, and asked him to direct me to the Ironworker foreman.

“Which company?” he said. “Herrick” was stenciled on the structural steel. “Herrick,” I said.

Glen Reed was a thick-shouldered bull of a man with blue eyes behind steel-rimmed glasses. “What do you know how to do?” he said.

“Nothing,” I said, “but I learn fast and work hard.”

“We’re not taking apprentices right now,” he said.

“Can I try again next week?” I asked.

“Up to you,” he answered.

The next week, I was back. “Where do you live?” he asked me this time.

“In the City, in the Mission District,” I said.

He nodded and told me to follow him to a nearby office. In 20 minutes, I had the signed letter. I squared away all my paperwork with the apprenticeship office in the afternoon and spent the evening practicing the knots on the sheet they provided.

In the morning I was introduced to my first partner and mentor, nom de guerre Packrat, an African-American journeyman out of Seattle who tucked his oiled curls in a plastic snood before putting on his hardhat. Moments later I was ten stories in the air with him, hanging floats, the platforms of steel angle and plywood and manila line from which welders worked. For much of the next year, I pulled 70-pound floats up the sides of high rises.

Graduating from the apprenticeship top of my class in 1988, and instrument man for American Bridge, charged with assuring that a major high rise went up plumb, I was named the union’s San Francisco Apprentice of the Year.

Ironwork is hard. Apart from its obvious dangers, it subjects a body to myriad small assaults. Steel has no concern for human flesh. Often, climbing into my pickup after work, I had to adjust my rearview mirror down to compensate for the day’s compression of my spine. My arrivals home with skin marked by bruises, cuts, scrapes, blisters, burns, and punctures cooled any temptation my sons might have felt to follow me into the trade.

But ironwork is joyous. To climb straight up steel columns and slide down them.…

To catch one end of a beam flown in and, working with just the tools in your hands and your partner at the beam’s other end, to nudge tons of steel enough so that you can bolt the new steel in place, not just the task but your lives in each other’s hands. To create, with pliers and shoulder and sometimes lap, the intricate armature of reinforcing rod that will make a brittle material the source of flights of bridge or building. To hook a leg under a beam’s top flange and bend down its opposite side and arc weld with heavy wire the bottom flange, and so to feel through a glove of thick leather and at just arm’s length the power that produces 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

To look down through the turn and turn and turn of the stairs you have erected, or along the miles of rails that will permit others to walk and stand where you have been first. To give the steel or reinforced concrete skeleton of a building its skin of concrete panels or metal-framed glass, and so bring it closer to life: These are just a few of our joys.

I was the first Ironworker one dim predawn up a high rise ascending above San Francisco. The manlift hadn’t yet been extended to the working floor, the uppermost decked floor. I climbed steel ladders to reach it and found that a red-tailed hawk had preceded me. It perched on a column stub at building’s edge. Bellying up to the perimeter cable at a respectful distance, I joined it, and together hawk and I watched the City and the bay and their creatures awaken.

In 1989 I stood up at a meeting of Ironworkers Local 377– San Francisco and said that in 1997 Hong Kong would go over to the People’s Republic, and that, with the ties of our large Chinese population to the colony, capital would seek refuge from the handover here. Businesses, and contractors to serve them, would necessarily follow. We could not expect these contractors to come to us. I suggested that we recruit in the Chinese community, to develop a cadre of Cantonese- and Mandarin-bilingual workers to help organize them. Some said that we should not favor one group over another, but others listened and remembered, among them Gene Vick, then a Business Representative of our local.

Ten years later, I was running crews on miscellaneous steel in an expansion of Stanford University’s engineering complex. As I drove home late one afternoon, a call came from the company office saying that a Gene Vick wanted to talk to me, and did I need his number? I didn’t. By then he’d become Business Manager, highest official in the local, apart from its president. He asked me to be an organizer. I passed my exit and drove straight to his office at the union hall to talk it over.

I was then being paid general foreman’s scale. An organizer’s job meant a pay cut to foreman’s. I’d turned down the chance at a superintendent’s job a few years before, because it would have kept me away too much from my young sons. Now they were older, but becoming an organizer would delay again my chances of promotion. I believed in the union’s uplift of workers, though. I believed that unions that do not organize, atrophy. I saw that our market share was declining; some of the lost work had gone to the now Chinese-American contractors I had predicted in 1989. I saw a very different opportunity. At the end of a half hour I said, “Give me two weeks to think.” In two weeks I called Gene to accept.

I confess not recalling whether it was a matter of law or advice, but I understood that I was to approach workers only on breaks. I understood “break” freely. A rodbuster straightened from his stoop at the end of a long run of snap-ties on a big rebar mat and stretched his back and his pliers hand: break time. A welder flipped up his hood and from a pocket unfolded a bandana and blew into it a smoke-streaked gob of snot: break time.

Workers in construction need to know an organizer understands their work and the content, pleasures, and struggles of their day. In California, much construction speaks Spanish, and in San Francisco Cantonese or Mandarin. My Spanish was adequate for this need, and from City College night classes I had enough Cantonese for a few simple exchanges. An organizer needs to arrive at a provisional evaluation of skill by watching a worker in action. Having worked with the tools, I met this need, too.

I had also been a general foreman—foreman over foremen, in construction a union-represented position. I knew the interactions of trades, relationships between prime contractor and subcontractors, flow of work from excavation to final punch list. I could read the work almost as I had once read Euclid. This was my other reason for stepping through a gate: to understand a contractor through its work.

At one City jobsite after work hours I found welds from a process that had been prohibited for structural use in seismic zones after the 1994 Northridge earthquake. This was not the only jobsite where I’d found such welds, nor the only contractor using them. In the shop behind our hiring hall where Ironworkers honed skills, I welded four samples, one each with slag on and slag off, of the prohibited and the most common approved processes. I visited the office of the job’s engineer of record and put them on his desk.

“These are what you should be getting; those are what you’re getting,” I told him.

The exposure of this faulty work might have enraged so many: contractors who would have to invest in more powerful and expensive welding machines and in acquiring new skills; any inspector who had approved the banned welds and so stood to lose a livelihood; maybe even the engineer, whose work might be cast into doubt, at the cost not just of income but of influence he had cultivated in City government. Considering how they might react, my wife and I discussed the possible need to relocate, maybe she and my sons separately from me.

Cops posed a lesser risk. California law has been interpreted to be more permissive of union representative visits to non-union sites than is the case in other states. An interpretation is only that, however, and cops may have their own notions of law. We organizers represented everyone working in our trade, union member or not. Whether or not this representation was encoded in law, we claimed by it the right to visit workers on any job. Our lawyers provided us a stapled sheaf of arguments to present to cops who thought otherwise, a document I left in the car. It didn’t fit in a pocket and, odd object in the hand of someone walking a construction site, might have hooked attention I didn’t want.

A construction union organizer does not approach workers with quite the same intent as organizers in other industries. Construction union certification elections are rare, for good reason. Construction employment is inherently temporary. The saw goes: We always work ourselves out of a job. A contractor might simply stop bidding or otherwise shape work so that by a scheduled election it can have shed its union-friendly workers and say, almost honestly, “We didn’t have work for them.”

The 1935 National Labor Relations Act acknowledges this with a special section for construction, numbered 8(f). In brief, Section 8(f) says a construction employer may be unionized without an election, through an agreement between employer and union that fulfills three conditions: (1) All employees become union members within seven days after the agreement’s effective date or subsequent hiring; (2) the employer gives the union “an opportunity to refer qualified applicants” whenever new employment becomes available; and (3) “such agreement specifies minimum training or experience qualifications for employment or provides for priority in opportunities for employment based upon length of service with such employer, or in the industry or in the particular geographical area.”

These agreements are commonly called “8(f)” agreements. In the form of “master agreements,” the type signed by the great majority of our employers, they are foundational, even existential for us. They delineate the hiring system, the so-called “hiring hall,” physical or not. They spell out wages and working conditions and grievance procedures. They establish trust funds ruled with equal votes by union and management to provide and administer benefits such as pensions and healthcare and to sustain apprenticeship training. Obtaining signatures on master agreements from non-union contractors is a primary object of construction organizing.

An employer that is organized—that is, that does not sign an 8(f) agreement through its own initiative—has pen put in hand by an arcane combination of pressures and persuasions, for which an understanding of the contractor and its work is necessary. One of the most effective pressures is “stripping.” When I stepped through a gate I wanted workers, first, to know and feel comfortable with us, to have someone to whom they could turn whenever they wanted. Frequently these initial acquaintances bloomed, and workers left their employers and came to work through us. In organizing parlance, we “stripped” them from their employers.

Stripping is scarcely possible except in booms. To bring more workers from outside the union into its hiring system when work is limited, as union members seek work to feed themselves and their families, is to court resentment and resultant disasters. When it is possible, though, it commences a virtuous cycle. The contractor who loses a worker often raises wages to keep others. As the contractor’s expenses rise, so usually do its bid prices. Union contractors, with better wages and benefit packages but on average a much more skilled workforce, compete better in the bidding. As they obtain a higher share of work, more stripping becomes possible.

And a non-union contractor sees that its best future is with the union.

Through stripping and other pressures and persuasions I and my south-of–Page Mill counterpart, under direction of the local’s then-president and brilliant chief organizer Dan Prince, in the dot-com boom brought many hundreds of workers into our ranks. We gave some with requisite skills in some aspect of the trade a limited “book,” as a journeylevel rodbuster, say, or welder, or rigger; after journeylevel training or time working with Ironworkers who had completed our apprenticeship, many went on to work in other parts of the trade. Most we slotted into our apprenticeship at levels we judged would honor their skills. We turned many non-union contractors union. We doubled the size of our local. It continues to grow and is one of the largest Ironworker locals in the country.

One day I stepped through the gate of a non-union contractor’s shop yard near San Francisco’s southern waterfront. I found a worker burning —that is, cutting with oxyacetylene torch—a thin steel plate. I recall it as quarter-inch thick, a few feet wide in one dimension, a bit less in the other. Closer, I saw that in fine soapstone on the plate he had marked out leaves, as of reeds, toward the ends of the wider dimension, and between them two carp leaping toward each other. It would be in the removal of steel, in its absence, that reeds and carp would live. His kerf had no chatter. The hanging slag was sparse. Most impressively, he controlled the heat so deftly that the thin plate didn’t warp at all. This was marvelous skill with a torch, well beyond mine.

Turning knobs, he shut off the torch. He pushed his green-tinted burning glasses up on his head.

Break time.

I soon exhausted my Cantonese and continued in English. He nodded and seemed to understand but didn’t reply. I left him my card. Call him L.

L didn’t come to me for months. When he did, I had moved on from my organizer’s job to replace a retiring business representative. My new responsibilities had little to do with non-union contractors, everything to do with union members and signatory employers. One of my daily tasks was dispatch of workers.

L appeared at the union hall’s service window to ask for me. I brought him into our executive board room and sat him at the conference table. He produced a photo: The steel plate, coated now in zinc, hung in a mansion’s garden; the carp leapt above an artificial stream.

“I don’t need that,” I told him. “I know who you are.”

He was slender, several inches shorter than me, large-eyed, long-faced, with a black mustache—not thick but creditable—and bristling black hair half-tamed with pomade. His fingers, too, were slender, like a pianist’s, I thought, not thickened by the work like mine. He had none of the strut of many an Ironworker. He seemed in fact gentle, almost shy. As he responded with documents but few words to what I asked, I concluded that he understood English but was reticent to speak. It was one skill that perhaps he hadn’t yet mastered.

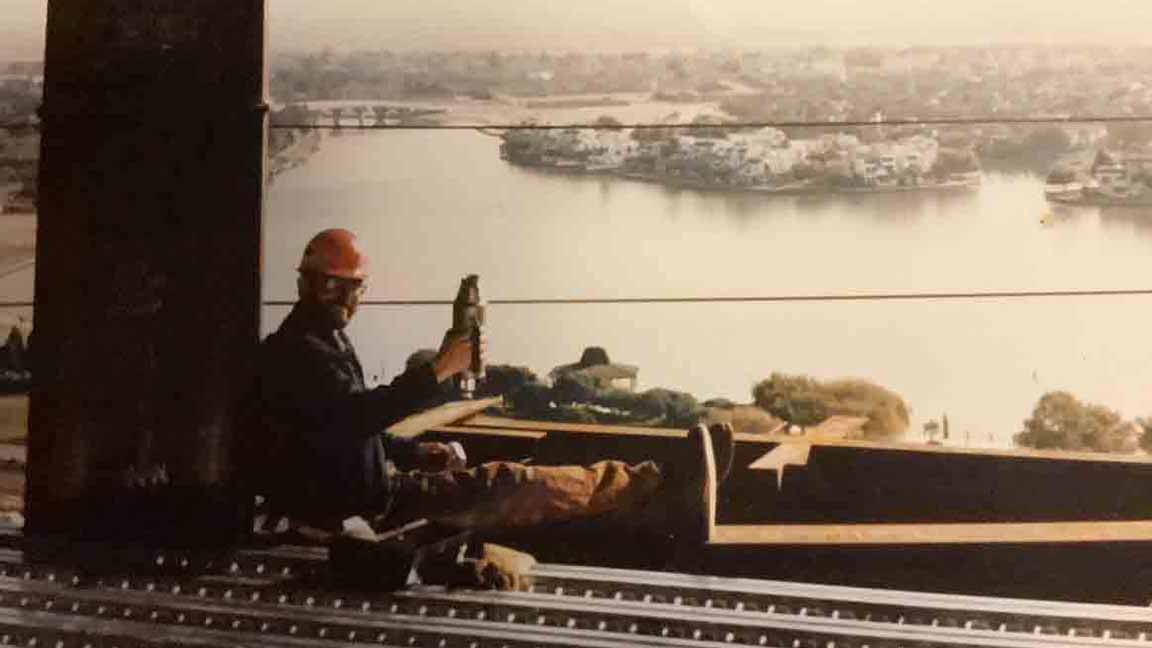

I had in my dispatch office an open call for an NR-232 Innershield welder, certified for full penetration, all positions, on the seismic retrofit of the south end of the Golden Gate Bridge. L showed me the required certifications and proof of years of employment in the trade. I had never seen his welding but was sure he approached it with the devotion to craft I had seen in his burning. I dispatched him to the bridge.

He returned, upset, some two hours later. The contractor’s safety officer, judging L’s apparent lack of English a danger on the job, had rejected the dispatch. I called one of the company’s owners. “I’m sending him back to you,” I said. “Work him. If he busts out, then return him to me.”

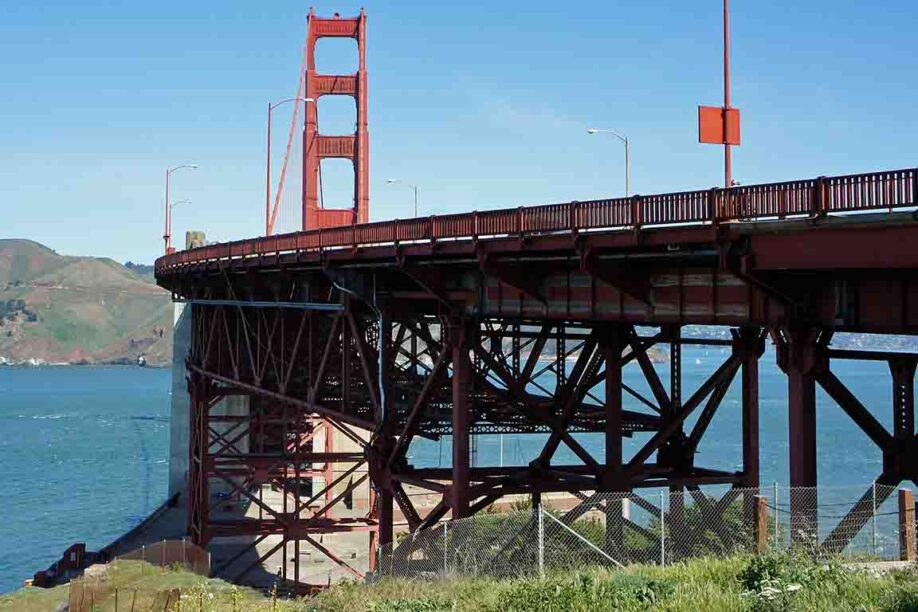

The Phase 2 seismic retrofit of the Golden Gate Bridge included reinforcement of the South Pylon, the concrete structure nearest the waters of the Gate, crowned with Art Deco fluting. Some five million pounds of steel plates from 3/8 inch to 1½ inches thick lined the pylon’s interior and were sandwiched on its exterior between the original structure and a new reinforced concrete skin. Interior plates were joined to exterior plates by threaded rods through holes drilled in the pylon’s walls. Inside and out, nearly seven miles of full-penetration welds united neighboring plates.

Literal tons of these welds are L’s.

L, his family; our union, our trade; one of the loveliest, grandest achievements of human mind and hand, our local monument for the world: All were better for my having stepped through a gate.

Not long after L came to us, his former employer signed our 8(f) master agreement.

Thank you for reading POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!