I STUMBLED UPON this ScreenRant listicle about what facts of American life international players find odd or amusing in “The Sims,” the popular video game franchise about dressing up and/or torturing bits of human-shaped data. (In much the same way the SimCity franchise reflects a neoliberal strain of urban design thinking particular to the U.S., The Sims’ attempts to “simulate” “normal” life helps reveal all the strange assumptions baked into American normality.) One entry in particular stood out: “Teens Having Legally Set Curfews In The Sims Is Strange To Many Players.”

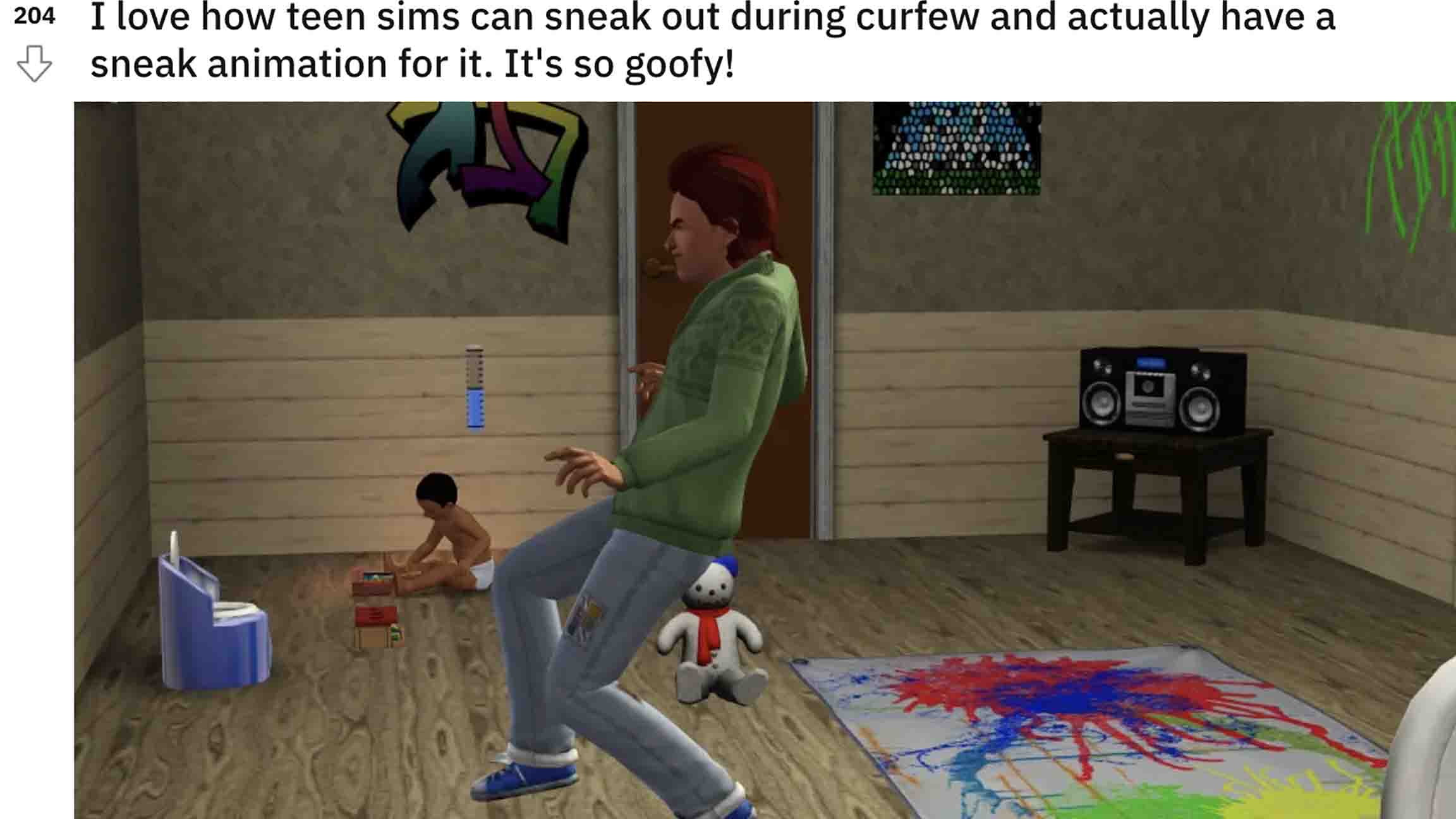

Now, “many players” turned out to be one Reddit user who appears to be Finnish, but both their comment and the content that led to it are worth highlighting:

In The Sims 3, teens that were out past 11pm by themselves could be caught and brought back to their home by a police car, mimicking the many real-life curfew laws that exist in some parts of the United States. This concept comes off as incredibly strange to many Simmers, with user kakkapieru incredulously asking, “someone pointed out the curfew, i remember when in sims 3 the police would get your teenagers after 23 and take them home??? […] is that [for real] or sims thing?”

Like yellow school buses and the absence of subsidized early childcare, this is, in fact, a very real thing in the United States. While youth curfews aren’t quite unheard of in the rest of the globe, we might lead the developed world in their ubiquity, punitiveness, and popularity.

Henry Grabar wrote a good thing in Slate this week about the continuing popularity of youth curfews in the U.S. as a response to social ills ranging from gun violence to general purpose hooliganism. Cities and counties from Chicago to Cherry Hill, New Jersey have introduced or strengthened bans on teens going out at certain hours or even going to the mall unattended. There is, as he writes, “just one problem”: “Even after more than a century of curfews in thousands of U.S. municipalities, no one seems to agree that they reduce crime.”

If anything, that is understating the case. There is effectively no evidence that they reduce violence and some studies suggest they may even increase it, by taking eyes off the streets or shifting policing energy to tracking down scofflaw teens. But, of course, in American criminal justice, “evidence” and “outcomes” hardly matter, as one remarkably honest police chief admits.

“I’m not concerned about studies that show curfew enforcement is not effective in reducing crime, because our curfew enforcement is not designed as a primary strategy to reduce violence,” Canton, Ohio police chief John Gabbard told the Canton Repository. Instead, the point is “to identify juveniles in need of more supervision, hold parents and guardians accountable, and to connect them to resources when appropriate before the juveniles are victims or perpetrators of violent crime.” The goal, as ever, is to use policing as a universal social welfare policy, and to treat our youth as problems rather than people.

Philadelphia provides an illustrative example of whether and how the actual efficacy of curfews at reducing “crime” plays any part in their use. The city council there recently made headlines for voting to make its stringent 10 p.m. curfew for people under 18 (and 9:30 for anyone under 13) permanent. Maybe we ought to give this policy some time before we cast judgment on it? We could give it like 68 years maybe? That’s how long Philadelphia’s already permanent youth curfew has been law, it turns out. And, as student journalists documented in 2018, city leaders have been periodically announcing crackdowns and amendments and increased enforcement every few years ever since. It seems that whatever problems a curfew is intended to solve have not been addressed by several decades of having one on the books. But this is the city that also installed youth-directed sonic weapons in public parks; the problem seems to be less teen behavior than teen existence.

If the goal was the safety of our vulnerable young people, it should seem obvious that a law that practically mandates that rule-following kids are home while rule-breaking ones are out would both punish the rule-following teens and lead to riskier behaviors by their less obedient counterparts. But I suspect our police and elected officials see that less as a flaw than as an opportunity to introduce future criminals to the criminal justice system as early as possible—not with any sort of positive intervention, but with an early taste of submission to authority.

This item originally appeared in the POPULA PLANET newsletter. Add your email here to receive it in your electronic mail box! Thank you for visiting POPULA!