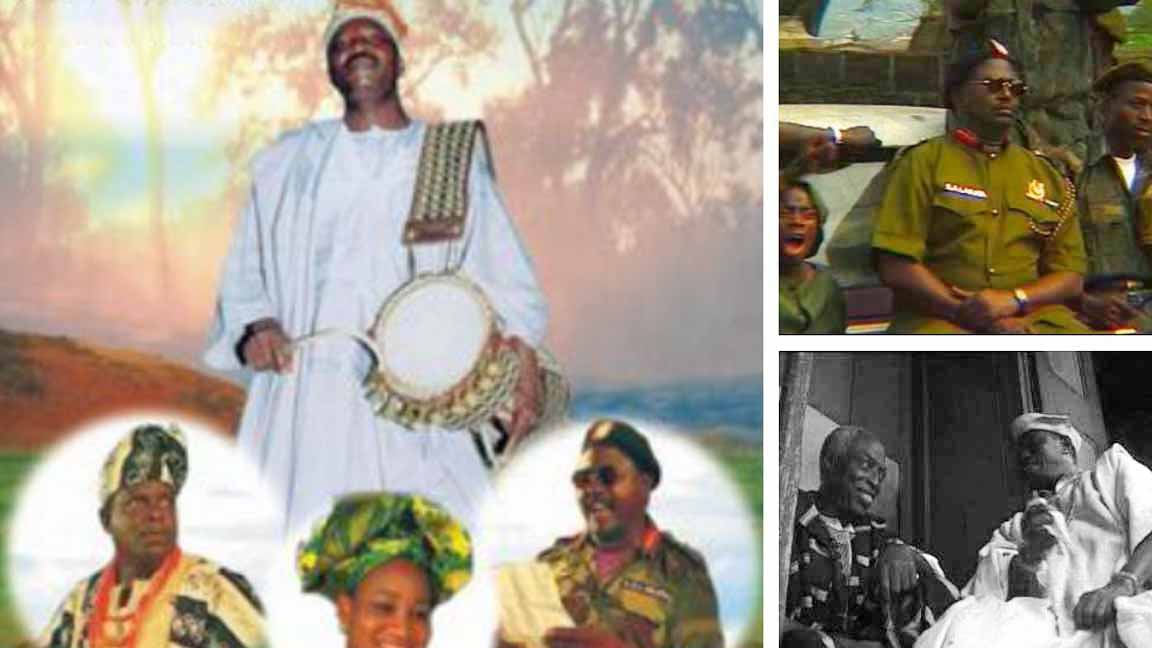

YORUBA CULTURAL PRACTICES blend with music to drive the narrative in the 1999 film Saworoide (The Brass Bell), directed by legendary Nigerian filmmaker Tunde Kelani. The film, set in the fictional land of Jogbo, is a barely veiled criticism of Nigerian politics. Kelani uses music in this film to express cultural exposition, praise-singing, and especially protest against the abuse of power.

Saworoide tells the story of the mystic connection between Jogbo, the Saworoide drum, the drummer Ayangalu, and the community’s king, Lapite, played by Kola Oyewo. Through rituals and incisions, the drum is mysteriously linked to the king, the physical crown, and to the drummer Ayangalu (chosen by Ifá, a Yoruba system of divination).

When he takes the throne, King Lapite refuses to follow traditional rituals, intended to prevent him from engaging in corruption. He suppresses all opposition and bribes local leaders in order to stay in power. However, Saworoide, the powerful symbol of authority in Jogbo, and its spiritual connection to the crown, make Lapite restless. Director Tunde Kelani subtly uses the magical Saworoide to represent moral authority, instead of using the Bible or the Quran. The film is brilliantly disguised as a fable, while displaying gripping political allegories to the military regime of the late military dictator, Sani Abacha.

The musical performances in this film, coupled with the actions, embody the political unrest that roiled Nigeria during the early ’90s, when the country seesawed between military coups and democratic regimes. Kelani shrewdly evaded censorship by communicating a message of dissent through music. As the military regime grows more violent and heavy-handed in the film, the musical landscape grows increasingly distorted and urgent..

On the surface, the film’s title implies music, fun, and merrymaking. But deep down it communicates the use of music as an instrument of justice for freedom fighters. It’s about the use of music to symbolize and strengthen those fighting for social change.

The parable of the drum as the voice of the people

The film’s introductory phrase: “Aso funfun lo sunkun aro, ipinle oro ni sunkun ekeji tantantan (white cloth longs for indigo dye, the first part of a statement cries for the second), is a well-defined folkloric expression culled from an Ifá verse. But instead of being uttered by an IfáIfa priest, it’s played on the Saworoide (talking drum) by a master drummer, an immediate signal that music will be used as a medium for transmitting the ideological, performative, and traditional elements typical of Kelaní’s productions.

The phrase plays a pivotal role in framing and setting the musical tone of the film, playing both at the opening and at the closing. Beyond its many allusions to real facts and personalities, all the musical roles in the film are played by real instrumentalists and singers who perform their real musical talents. The truth of this musicianship powerfully connects the plot to the true history, disguised as a fable.

In Yoruba land, age equals wisdom. To represent the wisdom of the elders, Kelani cast the erudite Adebayo Faleti as Baba Opalanba, an elderly griot who delivers sermon-like wisdom through poetry and idioms set to music.

In a particular sequence, Baba Opalanba pretends to be asleep as one of the corrupt chiefs (Lere Paimo) walks by and, believing Baba Opalanba to be asleep, insults the elderly man, upon which Baba Opalanba opens his eyes and laughs. Taken aback, the chief apologizes; in response, Baba Opalanba sings,

“Oro l’eye n gbo o

Oro l’eye n gbo o

eye o dede ba l’orule o

oro l’eye ngbo o.”

A bird that perches on the rooftop

is not taking a rest

but collecting information

Later, the chief explains to Baba Opalanba that the king didn’t swear the oath, or perform the compulsory ritual and incisions. This is an allegory of how people in power circumvent traditional procedures and responsibilities to avoid punishment. But can the king outsmart the gods?

Baba Opalanba replies that the king will die of a mysterious headache when he wears the crown, and the drummer Ayangalu beats the Saworoide drum. The chief berates Baba Opalanba for keeping such a deadly secret. In response, Baba Opalanba laughs and repeats his earlier adage.

In another scene, the chiefs celebrate the purchase of their new cars, and a journalist asks them where they got the money to buy such expensive cars. The chiefs call the palace policemen to drag the journalist out of the premises. Watching the incident from the palace steps, Baba Opalanba sings, “These chiefs are irresponsible, they promised the people that they would take care of the society; once in power, they steal and take bribes while the people suffer. But there will be repercussions.”

Youths gather at the palace and sing protest songs against the king for his corrupt practices. “The king is a renegade,” they chant. They also sing about deforestation, the destruction of farmlands, and the death of animals. Later they attack the loggers and pursue them out of the forest, and in celebration, they protest against the king with another song: “If Lapite is captured, he should be lynched.”

In the closing scene, Lagata, the military despot, has murdered Lapite, seizes power, and tortures whoever opposes him. The revolutionists seek to topple him using the magical power of the Saworoide drum and its chosen drummer.

In the final scenes of Saworoide, Kelani harnesses the supernatural power of music, making the magical drum the instrument through which divine justice is carried out. The end of the film communicates a layered message, suggesting both that karmic retribution awaits the corrupt, and that the people have the power to set that retribution in motion.

Thank you for visiting POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!