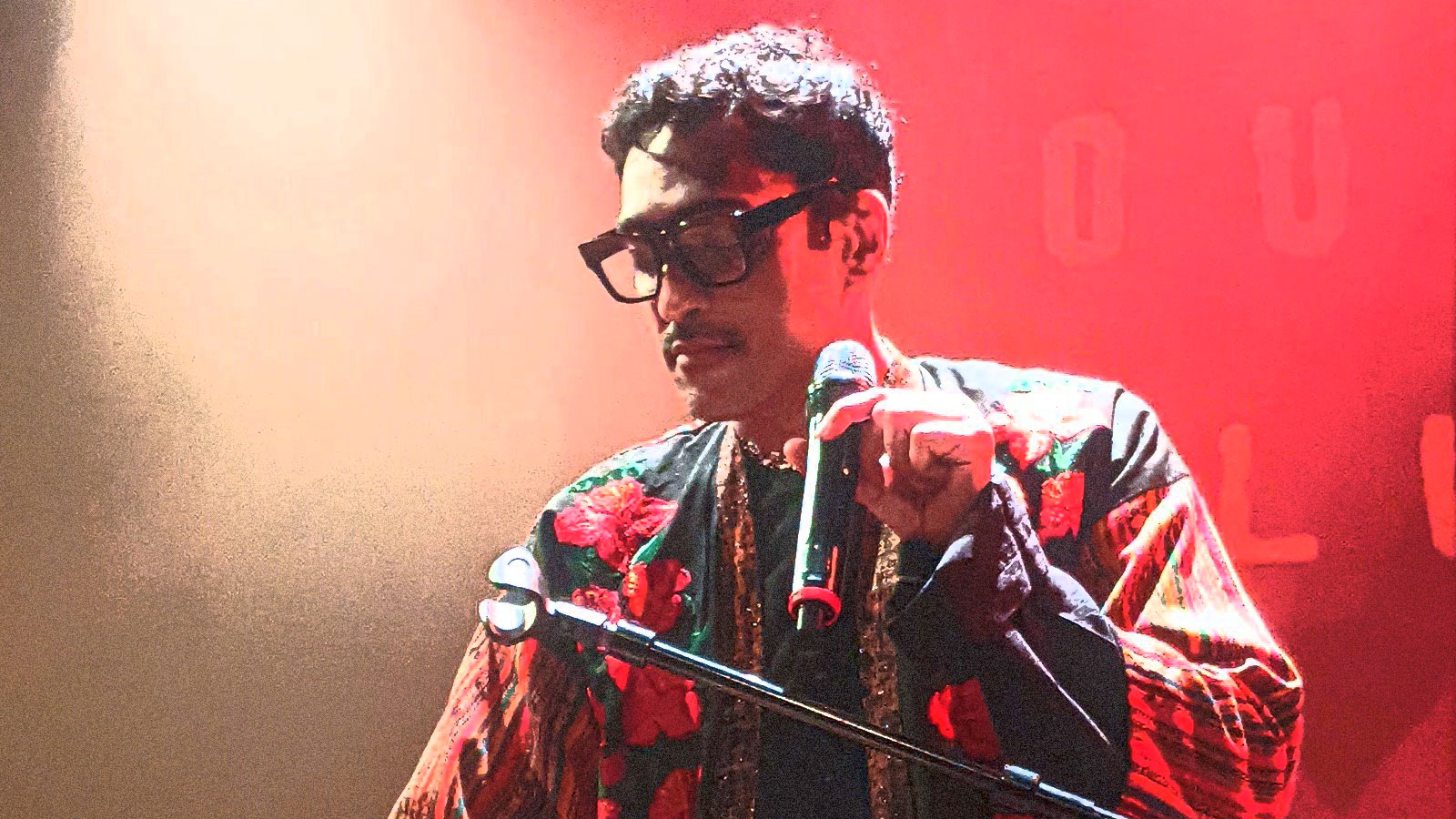

Pakistani novelist, journalist and singer Ali Sethi topped the charts across the world last year with Pasoori, a heartwrenching breakup song performed in a duet with debut singer Shae Gill. Sethi’s new album, Paniya, dropped in July; it’s a striking mix of classical poetry set against modern musical elements, addressing themes of longing, anticipation, and love. Packaging age-old poetry by Faiz and others in a modern synth envelope, Sethi embeds the classical past deep in a thrumming, electronic present.

In a notable shift from the homey vibe of his older videos like Dil Ki Khair, the new songs come with moody visuals, as in the video accompanying Raat Bhar. But it’s the sweetly piercing quality of Sethi’s diaphanous crooning that glides through you, stirring that unnameable something within.

Sethi has built a reputation as a modern artist reinterpreting ancient South Asian musical forms, especially the ghazal—a classic style of melancholic Indian love and protest song, with lyrical structures originating in Arabic poetry. To get a taste of ghazal, sample Begum Akhtar’s rendition of Woh Jo Humme Tumme Quarar Tha, and Jagjit Singh’s Tum Itna Jo Muskura Rahe Ho.

In song, Ali Sethi’s voice becomes a wild thing, cutting the air like a thousand needles puncturing the listener’s feverish skin. His music can easily silence a noisy pub, his voice boldly soaring between high notes and low. With Paniya, Sethi’s place as the modern-day maestro of ghazal is secured.

Raat Bhar

“Finally, the drought ends with Faiz’s gem in Ali’s voice,” reads one of many breathless comments on the YouTube video for this song. The collective ennui we’ve all been feeling lifted when Sethi took to the ghazal genre.

At first, Raat Bhar reminded me of former lovers, current crushes, and my husband, a million miles away—all at once. How was this possible? As I played this song again and again—on my TV, in my warmly lit bedroom, as the night descended into its deep reaches, a crepuscular sadness washed over me. A dampness I always associate with July nights hung in the air, mingling with the smells of cigarettes, antibiotics and matcha-lime body mist. But Raat Bhar did not discriminate, entertaining all my stray, varied emotions. The following day as I worked from home a friend joined me, and we listened again in my air-conditioned room in the Delhi heat as we tried to work.

Koi Khushboo badaltirahi pairaham pairaham

My friend asked me the meaning of pairaham but I drew a blank. He looked it up—it means outerwear, like a chemise. Faiz’s poetry burst out of the speakers in 2023 and had us look up khalis Urdu (most sincere Urdu) words.

A couple of weeks later, late on a Friday evening, I listened again.

Chaandni dil dukhati rahi raat bhar

Aapki yaad aati rahi, raat bhar, raat bhar

Even the moonlight brings heartache, all night long,

Thoughts of you overwhelm me, all night long

Now, Indian and Pakistani Twitter seem united—once again by a common hatred—in trolling Sethi for his personal life: He is one of Pakistan’s very few openly gay performers. I balanced my laptop on my knees, the earphones murmuring a soft whisper of Raat Bhar as I scrolled through the vitriol. I took a deep breath and murmured a tiny wish into the ashes of Delhi’s stale air. I gently told the world around me to take care of him, to protect this precious talent who has brought us only more and more love.

Kaase Kahu

After the first minute of this song, there’s a moment when the manjeera chimes for a second. Known mostly for its use in Hindu devotional singing, the manjeera in this song reminds me of the superhit song Agar Tum Saath Ho from the 2015 Hindi movie Tamasha.

Composed by Oscar-winning A.R. Rahman, the song catapulted to become that year’s top breakup anthem–and not only that year, but many more after that. I remember listening to the song on repeat for months and months even though I had suffered no such breakup myself. The lyrics by Irshad Kamil so wounded, the melody so singular, the singing by Arijit Singh and Alka Yagnik so moving, took us all lovesick wanderers to a faraway place where even breakups were so gorgeously full of meaning, and we’d have this glamorous song as a crutch. But it was only when I was listening to the song with a newfound love, both of us deep inside a moment of silent rumination, in a post-coital repose, and discovered that the background instrument chiming every other second was a manjeera. Our little north Indian hearts burst open with a joy so incandescent, we let out a little cry. We had discovered something novel yet commonplace in a song we’d both loved so passionately, so deeply, for months and months, by then.

We broke up within a few weeks of that evening.

The manjeera in Kaase Kahu took me to that bittersweet moment that was at once a memory of a love so profound and intense, but also a placeholder for a time that’ll maybe never return in my life, no matter how much I try to turn back the clock. Perhaps Sethi is singing to an effect like that. Perhaps he too wishes to be taken to a place like that.

Paaniya

This Saturday evening, I am on edge and exhausted in equal parts, and by 7:00 pm, I cup a mug of green tea, perched on the low-slung balcony chair, adjusting the pages of my notebook, listlessly penciling in a thought, as Paaniya hums in the background. It nudges me, provokes me, asking me questions I will never have answers to.

On days when life has been immensely hectic, the song feels like the soundtrack to an anxiety attack, an internal scream emerging out in the form of a song, or an anthem. On other days, when I’ve felt good vibes through the otherwise long days, the song morphs into a lullaby. There is an inert power hidden in its core that aches with the beauty and anxiety of a person in love. Life feels comforted in the lap of Sethi’s cloud-like light singing. Maybe this is what all of life really is. Listening to Sethi and gazing into the 340 AQI air, perched on the balcony and listening to the screeches of varied birds arranged ever so uncomfortably in the peepal tree behind my house.

Comments under the YouTube video for this song call Sethi a literal genius, and the song a therapy, even meditation. The sublime quality of his work should surprise no one; Sethi is after all trained by the doyenne of ghazal singing, Farida Khanum herself. His in-depth, almost academic rigour around South Asian culture, history, and heritage makes him one of the most aware and scholarly artists of his time. All of this at the ripe age of 39—we can continue, I hope, to expect such genius, and many more such meditative and therapeutic songs from him.

Paniya is perhaps the most abstract song from the eponymous album. When the song ends and the cloud lifts, I think of Sethi as a chameleon in the way his art takes the shape of the listener’s emotions.

Dil Mein Ab

Dil Mein Ab Yun

Tere bole huye gham aate hain

Jaese bichade hue kaabe mein

Sanam aate hain

My heart is now flooded

with memories of you that I had forgotten

Just as God appears in

previously deserted Holy places

Dil Mein Ab charts a bottomless grief as the track layers instruments alongside other sounds: minor-key notes, steely fiddle harmonics, murmurs, alaaps, and the subliminal flicker of the guitar.

I would’ve preferred Dil Mein Ab with a video like that of Sethi’s Rung, though, or perhaps a new interpretation of dancing in sorrow and remembrance. Faiz’s poetry transcending boundaries, once again: A dance of love between Faiz and Sethi for us modern-day star-crossed lovers.