There aren’t that many old buildings in Australia. Europeans invaded in 1788, we became a federated country in 1901, and we only started counting Indigenous people in our national census in 1967. Given how slow-going it has been to develop our moral architecture, it’s no surprise that our urban landscape lags behind.

One of the few exceptions is the quadrangle at The University of Sydney – my university. In keeping with the Australian elite’s fetish with British haute-culture, it is modelled in the style of similar buildings in Cambridge and Oxford. It has tall sandstone walls in a Neo-Gothic style. On the inside, there are four equally-sized patches of grass which served as tennis courts about a century ago. It is alleged that until very recently they were still finding old tennis balls nestled in the parapets at the top of the building.

In one corner there used to be a jacaranda tree that was planted in 1928. The common wisdom goes that if you weren’t studying for finals by the time the jacaranda bloomed, you were fucked. It died in 2016, not before scientists on campus spliced its DNA and planted a genetically identical replica in its place.

The top of the Quad houses a carillon, an instrument of which there are only three in the country. A carillon is a whole bunch of bells that chime together but when it plays it just sounds like someone going berserk in a doorbell store. In 2015, the University carillonist played ‘Sandstorm’ by Darude because of a dare on a promotional Facebook status. The architect wanted to give the building a distinctly Australian feel, so he added a couple of kangaroos as gargoyles.

In the late 1960s, a bunch of unruly students broke with political orthodoxy. Week after week, in the cover of night, they used thick black brushstrokes to write anti-Vietnam War messages on sandstone walls of the Quad, screeds against American militarism. They wrote their messages over the office of the Vice-Chancellor, and he reportedly grew furious at having to spend so much money getting people to scrub paint from the walls.

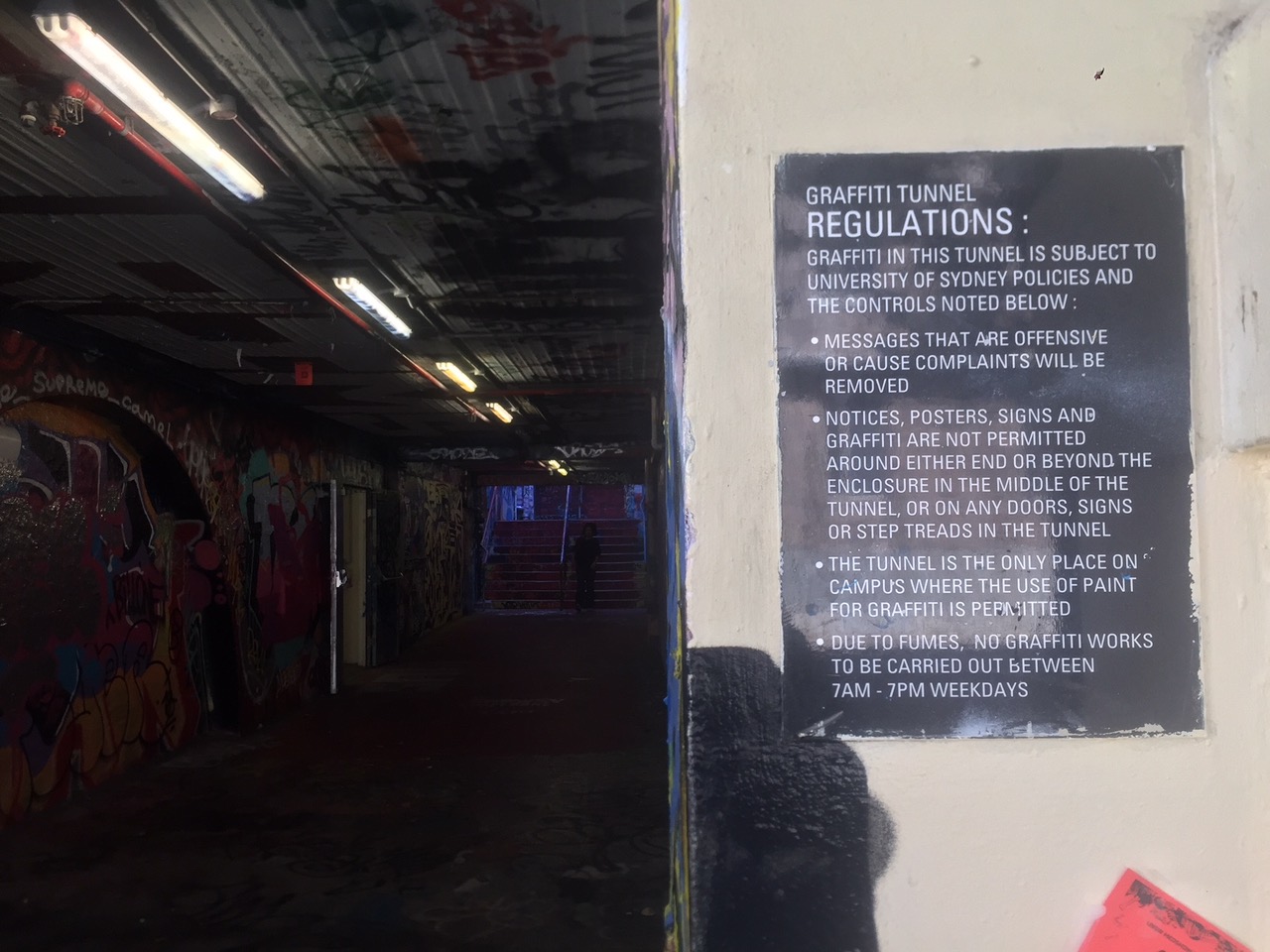

Attempting to make a concession to these unruly vandals, the University administration created the graffiti tunnel where vandals were free to scribble whatever they pleased. It seems most students nowadays are unaware of this history. The tunnel is a pedestrian thoroughfare, a fifty-metre underground walkway connecting Footbridge Theatre and Manning Bar. If you are of the opinion that graffiti is a crime, then the rationale for the tunnel is roughly analogous to opening an injection centre. They’re going to do it anyway, so we might as well control it.

The walls have been painted and re-painted so many times the tunnel must be about half of its original width. Everything is painted – the walls, the ceilings, the ground, the rails, the lattice, the doorframes. Scratch a finger down the wall, and you’d have the university’s history in rainbow layers under your fingernail.

Most of the graffiti in the tunnel is inane. Sometimes it’s an ornate tag that has obviously been doodled and re-doodled carefully in some notebook, sometimes it’s just a name and a year, or sometimes two names in a heart. There was a scandal only about a year ago after some kids defiled the walls with scrawled letters decrying the ‘Asian invasion’. Sometimes the graffiti shit-talks other graffiti. Occasionally people post angry notes in Calibri font size 20 about not painting over fresh stuff that obviously took a while to create.

If you stand in the tunnel long enough you start to feel boring. It’s like you’re made of wax with eggshell skin and dreary clothes. Maybe it’s the paint fumes concentrated in a confined space, or the schizophrenic energy of a thousand voices screaming into the centre of the tunnel, but the graffiti tunnel has always set me on edge. When you understand its history the very concept seems antithetical to the premise of graffiti.

For many, excessive graffiti is indicative of a broken society. It is visual pollution that indicates underlying disorder and unrest. But there is a profound, subversive empowerment in treating public property as a medium for personal messages. The tunnel is rebellion on the master’s terms.

The graffiti tunnel is not an artefact. It’s a living thing. I find it fascinating because it’s a space that is different every day, one that reflects the best and the worst of the young Australian psyche. What concerns me, though, is that it reflects our lifestyle too well; thoughts confined to the walls that encircle us. Scribbling on a wall away from the offices that matter, doing what we are told without even realising it.