I’m eating a giant bowl of mashed potatoes covered in melted cheese and that’s normal. It’s normal to take five pounds of leftover mashed potatoes from your fridge, grate a pound of cheese on top, microwave it, and then sit on the couch and eat it while staring blankly at the wall. This is how adult human beings eat lunch.

My daughter is trying out for cheerleading this week. They call it “cheer” now, but it’s just as bone-chilling as it was when I did it back in junior high school, which they now call “middle school.” Back then, I was high-strung and geeky, which they now call “anxious and socially awkward.” I wanted to make cheerleading so I could Be Somebody. While I eat six pounds of food for lunch (which they used to call “binge eating” but they now call “self-care”) I’m wondering if this is what my daughter wants, too.

My daughter never sweated a thing back in elementary school. She effortlessly made lots of ordinary, lovable elementary school friends. But seventh grade is different. You show up to middle school and your entire group of friends might just be judged as uncool by some other giant group of friends from an ever-so-slightly more sophisticated segment of your deeply idiotic suburb. You go to places like Starbucks or the fucking drug store next to the Starbucks (this is where they hang out now, instead of the Orange Julius) and even your closest friends are trying to ditch you, and you are also trying to ditch some of your other closest friends. Everyone is trying to win—or “out-beat the rest” as the grammatically challenged local cheerleaders put it in one of their cheers.

“Junior high is all about ditching and getting ditched,” I tell my daughter and her friend, trying to make the brutal realities of seventh grade sound faintly sporting instead of torturous. Even though I called middle school the wrong name again, they nod vigorously, so I throw in some wisdom about being who you are, where you are. Their eyes go dead. I wander off in search of something stiff to drink instead. Which is normal.

It’s normal to drink when you’re 48 years old and you’re looking a little grizzled, but you still want to look beautiful—magically, implausibly beautiful—possibly because you’ve always been attracted to the impossible. Some mornings I look in the mirror and I see Keith Richards. Other mornings I am Jeffrey Tambor. I put moisturizer on Tambor’s face anyway, as if, with enough moisture, I will transform him into a dewy nymph. I almost savor the despair of this moment, of wanting something so shallow and out of reach.

Being in seventh grade isn’t so different. You hate it but you also love it a tiny bit for the same reasons you hate it: the drama, the suffering, the competition. But you want to love it more. You want to be the one who is standing in the front, shouting something and looking cute doing it. You want to out-beat the rest.

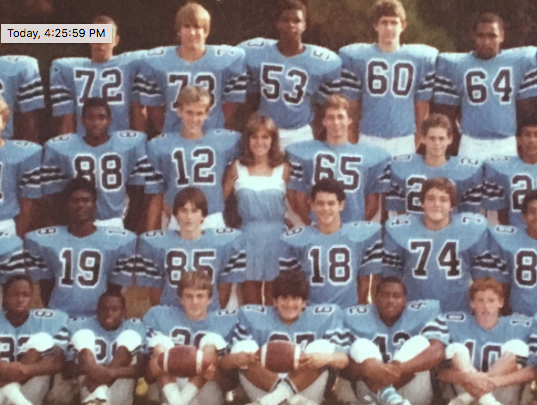

When I was in seventh grade, I had no dance or gymnastics experience, but I wanted the impossible, and so did my best friend. Every day after tryouts, we practiced our cheers and our jumps and yelled at each other, “NO BROKEN WRISTS!” and “THAT LOOKS SLOPPY, START OVER!” When we checked the list after school and saw that we made the team, just 8 slots available to 60 girls, we screamed and jumped around for five minutes straight because we knew that becoming cheerleaders would change everything. We would still be geeks, sure, but we would be visible geeks. People would hate us for no reason. That’s what we wanted. That is a normal thing to want at that age.

Now that I’m older and I’ve been hated for all kinds of reasons, I find cheerleading sexist and futile. I also know from personal experience that at least 91 percent of cheerleading coaches are sadists and sociopaths. That’s just a wild guess, but it feels statistically bulletproof inside of my head, where I spend most of my time these days. I’m middle-aged so I have all kinds of baseless and unfair opinions, which people used to call “being fucking delusional” but now refer to as “honoring your truth.”When you wake up in the morning looking like Burgess Meredith, what else do you have, really? You treasure your petty grievances and sweeping generalizations.

But I don’t tell my daughter these things. I don’t tell her harrowing stories about my high school cheerleading coach, who was a terrifying cross between an enthusiastic real estate agent and Bernadette Peters on a five-day bender. I don’t describe how we were forced to practice dangerous stunts in the gym without mats. Girls would be writhing in pain, saying their backs or heads hurt after a fall to the hard gym floor, and our coach would yelp in her scary baby voice, “You’re OK, you’re fine, get up!”

I also don’t tell her how much I loved wearing my uniform to school, or how satisfying it was to get attention from cute boys for the first time ever, after feeling doomed by my giant ugly glasses and unrelenting acne and bad fashion choices for so long. Out-beating the rest feels pretty goddamn great, I never say to her. I strongly recommend it.

I am being discreet, which is unusual for me. I want to help my daughter make the team. But I also feel like I should’ve prevented her from landing here, in this idiotic predicament in our idiotic suburb. Her dance is set to a hip-hop mix that begins with the words “My left stroke just went viral,” from “Humble” by Kendrick Lamar, but then it segues into a bad pastiche of watered-down beats that aren’t nearly as good as that song. My younger daughter asks me what “left stroke” means, but I ignore her because my older daughter is dancing and, in spite of my misgivings, I am already yelling, “NO BROKEN WRISTS!” and “THAT LOOKS SLOPPY, START OVER!” After a few rounds of this, she’s crying. I’m making cheerleading seem impossible. I am the worst kind of mother, a cartoonishly bossy, shallow nightmare. I don’t care. I can’t stop barking instructions, which seem to be about dancing but really boil down to how to be visible and cute and win by cheering someone else to victory. I never in a million years thought I would land here.

My daughter says she’ll freak out if she doesn’t make the team. This is normal, I think, but my pulse rate goes up anyway. I tell her that she should try on the despair of not making cheerleading right now, and maybe even cry about it, so she’s prepared when she sees the list at school and she’s not on it. This is terrible advice, advice so shitty that only a professional advice columnist could give it. “I feel like you don’t think I’m going to make it!” she yells at me. She hates me right now. I hate myself, too. All very normal and developmentally appropriate, for all involved.

It’s true that I feel like she might not make cheerleading, for the same reason I feel like I might get crushed by a mile-wide meteor at any second. I’ve always expected the worst. It’s a way of life. I want her to mimic my mindset, the way I mimicked my mother’s. That way no one wants something impossible that they can’t have. That way no one is ever disappointed. That way everyone aims low, and no one cares too much about something that’s out of their control. That way no one cries their eyes out when they read the list after school on Friday. My friend is a counselor at the school and says that it’s like the end of the world that day, hallways filled with sobbing girls. They have a nickname for that day. “Dies Dolorem,” or something like that. I might’ve made that up, too.

When you’re middle-aged, it’s normal to make shit up. It’s normal to be cynical about things you used to care about way too much, and it’s normal to find yourself seduced by those same things, out of the blue, in spite of your best intentions. It’s also normal to aim for the impossible while also expecting the worst. I want my daughter to make cheerleading, and I also don’t want her to make it. I want her to pick an activity that’s much less sexist and futile, but I also want her to out-beat the rest—not in spite of the fact that it’s absurd and shallow and twisted, but because of it.

Contrary to popular wisdom, growing older does not make you less conflicted. In fact, you become more and more conflicted by the second. You can see all sides of any given thing. It’s all stupid bullshit and you want all of it, everything, and you also want none of it, it can all go fuck itself. You are Jeffrey fucking Tambor and that’s delightful in its way, but you also want to be Meryl Streep or Chrissy Teigen or Angela Bassett instead.

When you’re this conflicted, it sets people on edge, particularly when those people are 11 years old and they’ve been practicing toe-touch jumps for three hours straight. That’s when you have to watch your step, or you might start spouting some of your baseless and unfair opinions (Who can do a fucking toe touch?) or airing your petty grievances, the ones you love so dearly but that other people like a tiny bit less. (What kind of a fucking sadist puts a toe-touch in the middle of a cheer for 11-year-olds?) Luckily, I am a grown adult who is in full control of her faculties, so after my daughter cries, I tone it the fuck down. I tell her she’s great at this, because she is great at it. And when she goes to bed, I tell her that I’m pretty sure she’ll make the team. She goes to bed happy.

I believe these words when I say them. But as I close her door, I’m filled with a sense of dread—not because I know what will happen, but because I don’t. Caring a lot makes you crazy, I think as I pour myself a drink. It feels crazy to care this much about someone who is not you, particularly when you care about them even more than you care about yourself, when you want the impossible for them, when you’d happily look like Walter Matthau from now on if it meant that that person could feel visible and good and right in their skin starting now until forever. It feels good to care that much, but it also kind of sucks.

So now I’m sitting on the couch, wondering if I’m a terrible mother. I wonder if I’ll ever say anything right again. That’s normal. I love my daughter. I love her much more than I can stand. It hurts sometimes. That’s normal. My drink is gone. We’re all out of mashed potatoes.

Heather Havrilesky