In the small, suburban, Conservative Ashkenazi community where I grew up, Yiddish warmed social interactions like background radiation. Words that had penetrated mainstream American English—putz, klutz, chutzpah, and kvetch—glowed in sitcom dialogue and newspaper print, where friends and relatives could point them out proudly, then complain about their embarrassing misuse. The untranslatable phrases would be used for comedic effect, and to occlude bits of gossip. But though my grandparents understood a great deal of the language, their children reached adulthood armed only with what they’d gleaned from private conversations: English for school, Hebrew for synagogue, they insisted; Yiddish was a distraction, a vice for those who refused to assimilate.

Only Mommy-Anna, my oddly nicknamed great-grandmother, ever finished a sentence in Yiddish in my presence. Perhaps, at the end of a long and linguistically promiscuous life, she could no longer restrict her thoughts to a single language.

The words I grew up knowing were peasant words, unfit for school and work, but used with family and close friends to communicate ideas too intimate for English formality: embarrassing social mishaps, sexual proclivities, casual racism. With my non-Jewish friends, I struggled with their English equivalents; crucial cultural contexts evaporated with every attempt at translation or explanation. Shonde could be translated as shame, for example, but my grandmother’s a shonde far di goyem was a vast and terrible malediction; she saved it for the Jewish travesties that put all of us at risk, the Roy Cohns, Bernie Madoffs, and Henry Kissingers, whose betrayals to the causes of Jewish safety, moral integrity, or cultural reputation were unspeakable in any other language. “A shame before the Gentiles” was flattened, sterilized; the results were useless.

Other terms were so rarified, so specific, that they weren’t mine until I experienced what they described. To shep naches means something like “derive gratification,” though it’s reserved for pride in another’s accomplishment. It can be applied as broadly as its cousin kvell; you can see people tweeting naches for births, scholarships, graduations, Jewish-adjacent TV shows, good publicity, even a crispy donut. But when I ask my elders to explain the Yiddish word to me, they speak of something more specific: naches fun kinder, joy from children; my childless uncle gestures to my infant daughter, explaining that one can shep naches from the children of others, if necessary, and when I think of her gummy grin, her chubby, pink hands trying to clap, I start to understand.

After pride in children, strangers on the Internet exult most in shepn naches from the existence of the state of Israel. I push back, believing, as I have since adolescence, that Israel suffers for its role as a diasporic fantasy; that an ethnostate has no divine right to its deep commitment to injustice; that Zion is a feeling, not a place, and that we deserve better than the psychic burden of defending a shonde like Netanyahu. But telling Jews to let go of the image of Israel as Zion can be like telling a prisoner to forget the world exists. It is an ancient, inherited coping mechanism, rooted in an abstract hope that sustained us for millennia; once concrete, that hope became a weapon.

But both the word naches and the concept it names are bigger, stranger, and more beautiful than their modern incarnations can evoke. What naches names could not exist without the Diaspora and the exile from ancient Palestine that set it in motion. It is a prayer to something removed from oneself, whether generationally or geographically; like all Jewish languages after exile, it is made of wandering and alienation, synthesized by creativity and illuminated by survival.

Naches was born in ancient Judea. An elderly apostate who wrote under the pseudonym Qohelet—meaning either “teacher” or “preacher,” known in Greek as Ecclesiastes—first recorded the concept in one of the most famously nihilistic poems in the Jewish canon, in which a version of naches appears in a kind of existential insult:

Should a man beget one hundred [children] and live many years,

and he will have much throughout the days of his years, but his soul will not be sated from all the good, neither did he have burial. I said that the stillborn is better than he.

For he comes in vanity and goes in darkness, and in darkness his

name is covered.

Moreover, he did not see the sun nor did he know [it]; this one has

more gratification than that one.

[Qohelet 6]

In the last verse, nakhát is the “gratification” of which the ill-fated man is deprived, the ancient Hebrew ancestor of naches. For all his prosperity, that man who “beget one hundred” fails to appreciate his good fortune. As the scholar Étan Levine argues, he is therefore a “normative fool”: he has attained the norms of happiness, the earthly successes and achievements, without absorbing the happiness itself. Such a man is worse off than “a stillborn child,” for a child who has no worldly experiences cannot covet material pleasures; this child has more nakhát than the fool.

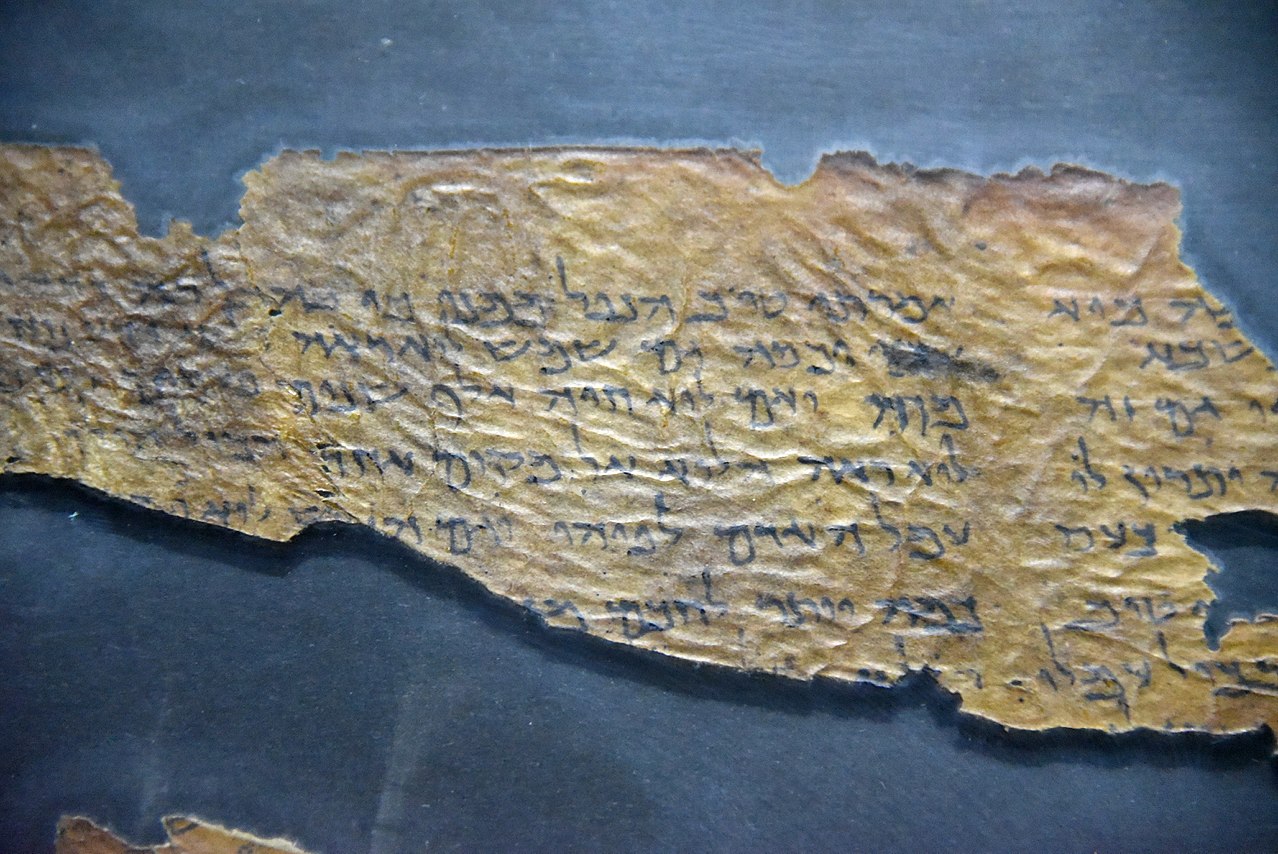

Nakhát’s phonological journey to naches might be unremarkable to a historical linguist. The distinctive Semitic ending softened to a sibilant and the syllabic emphasis jumped from second to first. But the uvular fricative, a sound that recalls to English speakers a theatrical throat-clearing as in or the Scots-English loch and which is a staple of Semitic languages like Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic, remains steadfast.

Despite their shared origins in Palestine, Jewish languages other than the reconstructed Hebrew are not Semitic in structure. After the fall of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Hebrew- and Aramaic-speaking Jews fled in every direction in search of safety, into Europe, South Asia, and North Africa. The speakers of proto-Yiddish trudged on winding paths through Central and Western Europe, and the prevailing scholarship has the language first developing in medieval Bavaria. Over those first few hundreds of years of interfaith coexistence, Jewish migrants absorbed the surrounding Germanic grammar and infused it with Semitic vocabulary. When the Black Plague’s attendant spike in anti-Semitic violence scattered the community in all directions, a majority of Yiddish speakers wound up in the “Pale of Settlement,” a desolate, open-air ghetto grudgingly offered by Imperial Russia. There, a nascent Yiddish adopted a slew of Slavic words, though it held on to its Bavarian syntax.

When languages come in contact with one another, “the direction and extent of [linguistic] interference, as well as the kinds of features transferred, are socially determined,” as the linguist Shana Poplack observes; the way speaker groups coexist—or don’t—helps shape the way their languages interact and evolve. Jewish languages are like Diaspora Jews themselves: fluid, isolated, codependent, and always under threat. As Chaim Rabin puts it, it’s the “special atmosphere” of their usage that defines Jewish languages, the unusual traits of Jewish diglossia, or community-level bilingualism. It was the Germanic-speaking native country of the first forms of Yiddish, for example, that turned nakhát into naches.

But it was the geographical journey, with its cycles of uncertain peace and certain persecution, that transformed Qohelet’s religious imperative into a cultural artifact.

It might seem facile to say that naches became a one-word mantra for Jewish survival in a hostile environment, but that doesn’t make it untrue. Indeed, if we translate the word that Qohelet used into English—or try to explain the shep naches on Twitter—it’s too easy to come up with the same sentiment for both, the same flattened and sterilized sense of “derive gratification.” For one thing, both nakhát and naches allude to joy derived from a specific and culturally-determined source: joy that sustains, supports, and distracts from pain. For another, and more importantly, naches has evolved enormously over the long centuries of diaspora; it doesn’t, and can’t, mean the same thing as a nakhát in Judea.

Today’s naches is a Jewish pleasure located somewhere between gratification and pride, between present-day nihilism and the vague and glorious future in a place we tell one another is reserved for us. And the conflation of contentment with pride in one’s children makes sense if you think about the image of a free life for one’s children which sustained the culture through inconceivable persecution, through two thousand years of fleeing and fighting. The fantasy of that promised future—that was transplanted over time into the physical space of Palestine and Israel—eventually fused into the closest Jewish equivalent to the Christian concept of Heaven. It was something to keep moving towards. For Jews of the Diaspora, our progeny is the afterlife.

Naches is faith that one’s children will someday have a safe home, a faith that the whole narrative of Jewish survival is greater than the suffering of the present. On the holiest days of the Jewish year, we recite L’shanah haba’ah b’Yerushalayim, “Next year in Jerusalem.” The invocation of that future in Jerusalem—a place or an idea—was first recorded roughly six hundred years ago. It’s a long timeline if you’re planning the coming year; if you’re imagining a better life for your descendants, however, it’s just about right.

For most Jews, the better life remains elsewhere. Somewhere between half and two-thirds of us live outside of Israel and Palestine, where the anti-Semitism is mounting in ferocity once again. For us, Israel’s existence still offers an emergency refuge. The thought of a future in which our children can have normal worries is so powerful that it can blind us to what has become of our symbol when it became a nation-state. The modern nation that occupies that land contains real people susceptible to the weaknesses of mortal politics, with the expected waves of racism and authoritarianism. What Israel defends with warfare and political suppression is not—and cannot be—the source of our naches. Our children deserve better than survival at such a high moral cost. We can derive joy from their future somewhere else—geographically, metaphysically, spiritually.

The rest of Qohelet is a bitter lament on men’s vanity, women’s empty-headedness, and the futility of all forms of quotidian pleasure; throughout his verses, the Teacher returns to the ephemeral nature of all things and the unpredictable cruelty of the will of G-d. “The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning,” writes the sage in 7:4; in dwelling on his death and its aftermath (including the fate of his children), the wise man wards off the fear of death that plagues the fool. He imbues his living days with awareness of his mortality. The wise man’s thoughts are holy because he knows they cannot last: the experience of his good fortune keeps him anchored in the present.

Qohelet was writing before Jewishness became synonymous with a life of uncertainty, but his insistence that all pleasure turns to ashes remains a powerful force in Jewish thought. No matter the circumstances of the present, the future is untouchable.

Since the Holocaust, there’s been a (possibly apocryphal) story about a group of Jewish prisoners in Lublin, a city in Poland where no more than a few hundred Jews survived from a prewar population of 42,000. In the story, the prisoners are taken to a field by Nazis where they’re ordered to sing and dance for their captors’ amusement. One weak voice intones the first line of a Yiddish folk song, Lomr zich iberbetn (“Let’s get along”), but the refrain doesn’t catch on, or is silenced. Then another voice offers a different set of lyrics, igniting a defiant chorus: Mir veln zey iberlebn. “We shall outlive them.”

Lynne Peskoe-Yang