In my last year of high school, I carried seven-hundred-odd pages of the hardcover The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, everywhere I went. It was in pristine condition when I first checked it out from the media center, the cellophane of its protective cover sticking to my palms with skin oil and sweat. My wrist would ache from cradling its density at my side, and as I made my way through the halls of my overwhelmingly white public school–built two decades after desegregation to serve a wealthy white tax base–Hughes’s lines would reverberate with depressing relevance.

I carried the book around because I loved it, and for the same reason my younger brother wore his Public Enemy shirt to class, to announce myself in a whisper: I was a reader, a black reader. I renewed Hughes from the school library for months, wandering with him down the divergent phases of his poetic career towards my own graduation and imminent departure for New York, the dreamer, the lyricist, the communist. It was not lost on me that I was able to keep checking it out because no one else at school requested it.

I thought about stealing it, about making it mine forever. But though I eventually returned it, in slightly less than pristine condition, the book had done its work. I had claimed it, it had claimed me, led me to Leadbelly and Marx and, eventually, to Harlem, where I lived in an apartment around the corner from Una Mulzac’s Liberation Books, a former haven for black readers revealed to have been surveilled by the publically-funded US Federal Bureau of Investigations.

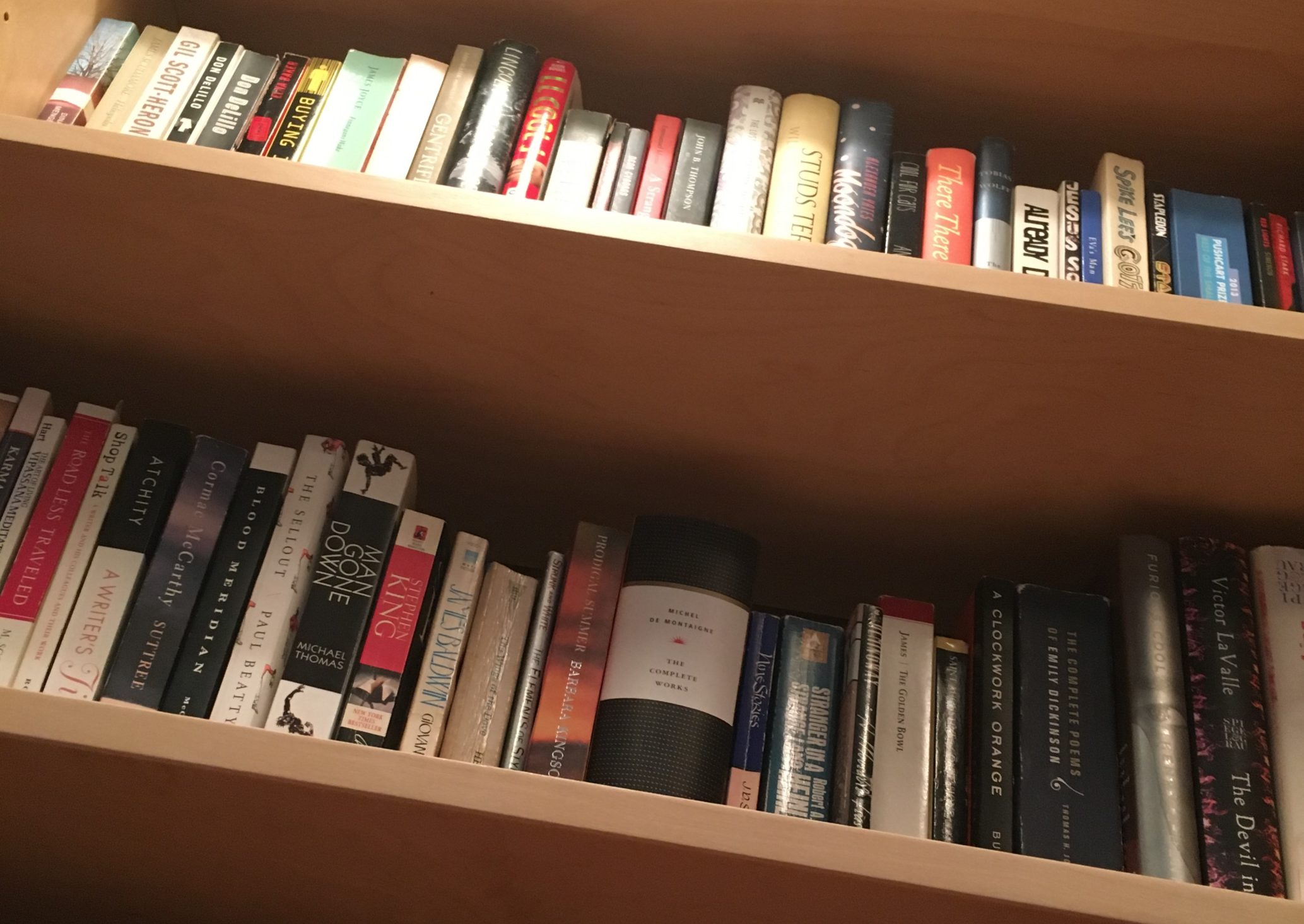

Last year, I finally decided to own a copy of The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. But when its 736 pages arrived—ordered instantly from and delivered the next day by Amazon, a private company—I recognized my mistake: the book did not spark joy (as the one who has sparked so much ire among the book-fetishizing world would put it). The book could not mean to me now what it had meant to me then; owning it could not recapture the electricity of that reading experience, nor deepen my personal claim. Instead, it sits on my shelf gathering dust, like so many other volumes in my private library. Instead of my past, these books only conjure visions of the inevitable future, of the day when I will be dead, and someone else is burdened with the task of executing my will and dismantling the fortress of books separating my body from the world.

It troubles me. I own many books. I’d like each to represent a reading experience I’ve had or hope to. But I must admit that each, also, represents a transaction, an exchange that conferred private ownership on me. Perhaps the trouble is in that space, between reading and owning, between the personal and the private.

For me, this confusion started with Hiram’s Red Shirt, the story of a poor white farmer named Hiram who keeps patching holes in his favorite shirt, at first with other parts of the shirt then with other articles of clothing, until he winds up sacrificing damn near his entire wardrobe for the single shirt, finally caving and buying a new shirt. Rather than get rid of the old shirt, Hiram keeps the useless, ruined article as a memento.

Owning this book tore the first of many beautiful book-shaped holes in me; I patched it, at first, by reading the book over and over, memorizing its dozen or so pages and color illustrations until the thing was as tattered as the poor farmer’s shirt, the cover gone, the spine spindly, the book object an uncanny manifestation of subject. Like Hiram with his shirt, I kept the book after I had outgrown it as a kind of record of self, in my first book.

Since receiving Hiram’s Red Shirt on my fifth birthday, a disproportionate amount of what I own is books, books which have patched or opened similar rips, and a feedback loop of conflations grows out of them: reading with one’s personal library, one’s personal library with the owner’s literary ability, one’s literary ability with the extent of one’s reading, and so on, ad absurdum.

“It’s like a library in here,” an uncle recently remarked during a visit to my apartment, and his tone was an octave below praise.

But the books I own are not a library. They are a private collection I have been amassing since childhood, when I stopped spending money on Jordans and Cross Colours in favor of expensive hardcovers like The Oxford Complete Shakespeare. I never could read more than a sonnet or a scene on account of its weight, almost-illegibly small type, and onion-skin pages, and I have since misplaced it. But from middle school to college, the only thing that pleased me as much as standing before my spurting bookcase was standing in the mirror before my growing body: Shakespeare, an ancient Webster’s I’d inherited from my father, my humanities course books, Hiram’s Red Shirt, my mother’s Amharic book of psalms. It was a mirror of who I was and wanted to be; I was my books, my books were me, and the desire to write books and live through them confused the matter ever more.

I know that Marie Kondo is right, that I have never needed more than thirty books at any time, but a full purge would kill off older parts of me, or keep my future self from discovery; owning books feels like a way of staving off death. And yet Thomas Jefferson owned books with the same avidity as he owned black bodies like mine and Karl Lagerfeld was as much a book-hoarder as he was a bigot. I know that book collections become a pantomime of erudition, or a flex, as I often think when walking past the lit windows of tony brownstones in Brooklyn and catch sight of a large built-in bookcase. And yet when I have ever passed one without the tug of desire?

No one hoards books like Amazon, owned by the world’s wealthiest human and named after the planet’s greatest (and fastest-declining) carbon dioxide sink; Amazon, a company with one of the worst track records of addressing our climate crisis, began as an online bookseller, something no one knows better than a book hoarder like me.

As parts of the world with greater private capital lay claim to more and more of our public resources–deepening racial and economic segregation, just as at my high school–Amazon exemplifies these shifts, from public to private. Book-hoarding is less cute if you think of it as book-privatizing. But my reading is governed by my personal library, not the public one a few stops away on the Metropolitan Transit Authority; my books reflect less the extent of my reading and erudition than they do a grand shift in resources from the public to the private. And my personal library’s explosion has so much to do with Amazon, like the trouble I have whenever it’s time to move from one house to another. Reading books helped me move through high school hallways, to New York, to Harlem, and owning them now inhibits me and weighs me down. I buy with a single click, and my knee clicks as I haul yet another bin of books up flights of stairs.

I remember the thrilling convenience of buying a book online for the first time, and the sudden insatiable 2AM desire to have The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes or Hiram’s Red Shirt. Because I can! That feeling is separate from the responsibility of owning that book, separate from the act, spread out over hours, days, and weeks, of reading the book, separate even from the feeling of being possessed by one. I know this. And yet the moment when the mouse hovers over the purchase button contains the promise of transformation, a hope that obliterates the knowledge there is no more space on the shelves. It’s a feeling far less tidy, and far less personal, than joy.

Mik Awake