Download any Chinese lesbian dating app–Rela, LesPark, or LesDo–and you’ll get the same prompts to input your nickname, photo, and also your identity: are you T, P, or something else?

On the surface, it seems clear enough: T comes from the English word “tomboy” while P supposedly originates from “po” (婆, part of the Chinese word for wife, 老婆), although some people say it stands for “pretty girl.” At a glance, then, T and P would seem to correspond to butch and femme, sexual and social roles for queer women in Chinese-speaking cultures, existing in opposition and symbiosis: T is masculine, P is feminine; T is handsome, P is pretty; T tops, P bottoms. The assumption is that they go together, and above all, that the T delivers the fuck and the P receives it.

What should be clear isn’t always so, however. The first time I encountered T and P in action was in 2010 at a lesbian bar in Shanghai called Red Station. I was still a girl in those days, and before I even stepped in the door, a T told me I was pretty. Then another T asked if I was a P. I was confused: Wasn’t it supposed to be obvious?

T/P certainly exist to facilitate sex. But if butch and femme were born in the 1950s, the T/P schema is part of a queer youth subculture that dates from the internet era, which its fluidity reflects. It’s as much verbal as visual, and less rigid. T and P don’t always pair up with each other, for example; there’s also “TTL” for T-on-T loving, or “PPL” for Ps paired with other Ps. Bisexuals and pansexuals are excluded from the schema, regardless of their gender presentation (in dating apps, “bi” is its own label), while a growing proportion of Chinese queer women opt out of this binary altogether, labelling themselves V for “versatile,” H for “half,” or 不分 meaning “no distinction.” But the category contains many different shades and flavours, from the 铁T (“iron T”) or stone butch whose sexual body parts are untouchable, to the 娘T (“effeminate T”) whose feminine appearance belies a T interior.

A T is also not always a woman: T “blurs the distinction between butch and transgender identities,” as Ana Huang observes, and many Ts use men’s names and refer to each other as brothers. When Leslie Feinberg’s iconic Stone Butch Blues was translated into Chinese by Taiwanese queer scholar Josephine Ho, Huang points out that “Butch” became T in the title, but “transgender” (跨性别) was in the title of the preface.

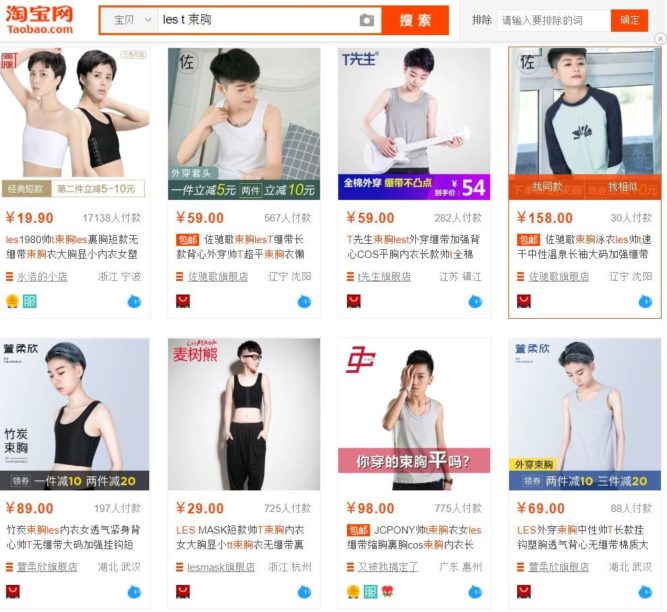

A more mundane example of the term’s fluidity: when shopping for chest-flattening binders, I found that “les T” was a helpful search term on the e-commerce platform Taobao, but “trans” (跨性别) didn’t bring up any results.

“The borders between butch women, masculine genderqueer people, and trans men are clearer in theory than in practice,” as Evan Urquhart writes. Butches may resent their identity being reduced to a stepping stone towards manhood–understandably!–but people do cross over from butch to trans (and vice versa). And in China, as elsewhere, some are keen to police these borders; at the intersection of misogyny and pedantry lies a flaming heap of rules on how to be a T. I’ve heard trans guys mock Ts as being too gutless to take testosterone; I’ve seen Ts scold each other for laughing in a high pitch, or for sitting with their legs crossed thigh-over-thigh instead of ankle-over-knee.

Yet for all the homophobia and gender regulation across Chinese society, Ts also find acceptance for who they are, even adulation. Indeed, female masculinity commands a certain respect in the cultural landscape of mainland China, as Jamie J. Zhao explains (a lecturer on gender, sexuality and pop culture at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University). In the Mao era, the ideal woman was stoic, sensible, and muscular. As a result, androgyny or masculinity in women is typically seen as an emblem of feminist expression rather than indicating lesbianism. “Ts, or lesbian female masculinity in general, were unfortunately folded back and silenced in this discourse,” she says.

Zhao says she first encountered the term T around 2004-2005, when she saw it used in Chinese lesbian and gay online forums to describe Taiwanese reality TV stars as well as characters on U.S. television show The L Word. Used to describe young, handsome, and fashionable masculine lesbians, it was explicitly linked to queerness. “As a quite visibly masculine female . . . I don’t mind being called a Tomboy/T,” she says.

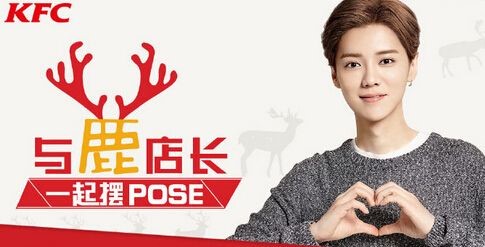

Tomboyish women attract mass appeal in Chinese pop culture, even as their sexuality is often obscured. Though there are few self-identified T celebrities in mainland China, audiences have embraced a succession of androgynous-styled pop idols such as Sunnee, Li Yuchun (Chris Lee), and Leah Dou, whose fangirls call her their “husband.” The tomboy aesthetic is so popular, in fact, that while some people criticise Ts for “imitating” men, you could equally argue that cisgender men are emulating tomboys. The most bankable male stars in China today are “little fresh meats” whose appeal lies in exactly the blend of swagger and softness that Ts have perfected — and whom unwitting foreigners like myself often mistake for cute lesbians.

Is it lesbians who look like Justin Bieber or male celebrities who are increasingly taking style cues from queer women? KFC ad campaigns featuring Super Girl winner Li Yuchun (above) and boy band idol Lu Han (below) show that it’s a chicken-or-egg question.

However, Zhao also feels that there is ageism and lookism embedded in the term. Because T identity privileges youth and beauty, it becomes less “liveable” for those who are older, lower class, or less cosmopolitan. “Growing old for Ts seems to be an excruciating, lonely, daunting process,” Zhao says. The T nightmare scenario is to spend their twenties being the perfect boyfriend to a P who will ultimately leave to marry a man.

As a term that collates gender identity, gender expression, sexual orientation, and sexual role, T has its roots in queer women’s culture but branches into transmasculinity. For Huang, therefore, it offers possibilities for imagining T “outside of a transgender/lesbian binary,” and “a melding of both gender and sexuality into one categorization system.” Though many cultures have historically conflated them, contemporary trans discourse commonly separates sexual orientation and gender identity. In China too, even as T identity implies both a masculine sexual role and attraction to women, there are trans people who stress that gender is not sexuality.

When I call myself T and gender-fluid, it’s in recognition of the shifting space I already occupy: some people see me as female and others as male and neither are wrong exactly. Others may use the same labels and pronouns as me and mean something entirely different by them. But connotation overrides denotation, sometimes; a descriptive understanding of how language is used can be more useful than the prescribed intent. How words like T, butch, stone, trans, lesbian, woman and man are used in real life is more liquid, sensual, and ludic than their dictionary definitions. After all, even a simple word like “cock” can mean a dildo, a penis, a clitoris, a nipple, or a fist. As Huang cites queer Chinese activist Xian explaining, T/P is a tool, like business cards you can change depending on the setting and your objectives: “T/P is most importantly serving a goal—who do you want to fuck?”

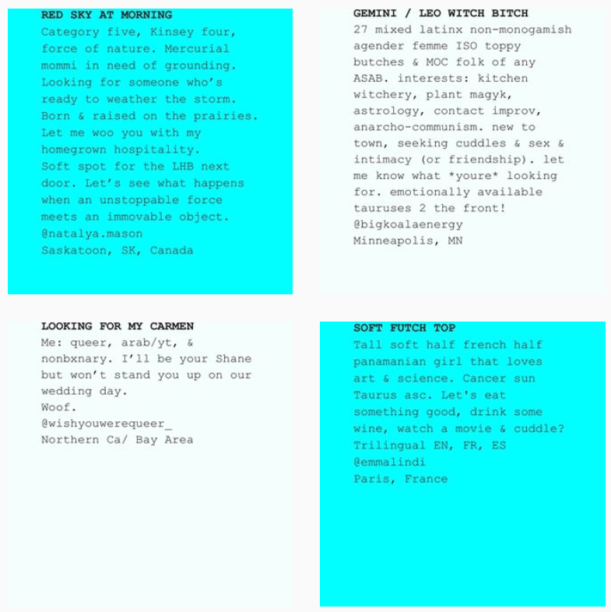

It’s no surprise that Chinese queers would draw from English terms and the Latin alphabet to articulate things best said obliquely. From the 19th-century cant of Polari to the vocabulary of Black and Latinx ball culture, queer cultures have a long tradition of linguistic innovation; slang is an art form, a playground and a laboratory. It lets us invent new ways of being and relating and desiring—as with the wealth of jargon used in polyamory and BDSM networks—while also keeping secrets hidden in plain sight. Learning the lingo is part of the initiation into queer communities, but not only for privacy and protection: it’s sexy to say things so only your intended understands. That’s part of the draw of hanky code or the queer dating platform _personals_ where many of the ads showcase language that’s incomprehensible to heteros.

There’s a feature on online dating platform OkCupid where you can select “I don’t want to see or be seen by straight people,” and there are moments when I want this option in real life. Invisible, invincible. The motifs of queer women’s culture often have as much to do with being illegible, unattractive, or unavailable to a male gaze as they do with appealing to women. Sometimes, this leads to a sort of separatist sentiment that often excludes bisexual and transgender women and reinforces gender binaries. Nonetheless, honouring and celebrating impenetrability—both physical and cultural—can be a radical proposition when dominant narratives of women’s sexuality revolve around receiving.

Consider the word “voluptuous”: meaning “of desires and appetites” when it first entered English, a voluptuous person was a hedonist, broadly speaking. Seven centuries later, “voluptuous” almost exclusively describes tits and ass, making a woman voluptuous by virtue of her shape, not her appetite. This slippage from desirous to desirable is so common in how female sexuality is seen, but T, like stone, offers the possibility of a sexuality that’s active yet untouchable.

When I was cruising China’s les bars in 2010, it had felt like everyone was either an androgynous, chain-smoking T or a coquettish, long-haired P. But now there are more and more opt-outs, especially in big cities; when I left Shanghai in late 2018, the once-pervasive dynamic was looking a little provincial (which in China is the cultural kiss of death). Meanwhile, trans men are becoming more visible and vocal, and while it’s thrilling to see China’s trans movement grow, it can overshadow the specific T subculture, which doesn’t fit as neatly into the Western and increasingly global trans discourse.

For all the advances that the global LGBTIQ movement has fought and won–in legal rights, health care, social recognition, and other fields–certain experiences and understandings can be privileged over others. We are supposed to say that sexual orientation is divorced from gender identity, that gender and sexuality are divorced from trauma, that our identities are indisputable, innate and independent of our relationships. Anything less is suspect.

T is a spanner in the works. It interrupts the narrative that the only authentic way to be something is to be always already that thing (lesbian, bisexual, a woman, a man). It respects becoming and relationality and interconnectedness. It has space to hold everything that you are; it moulds to the shape of you. I love it for that.

Jingua Qian