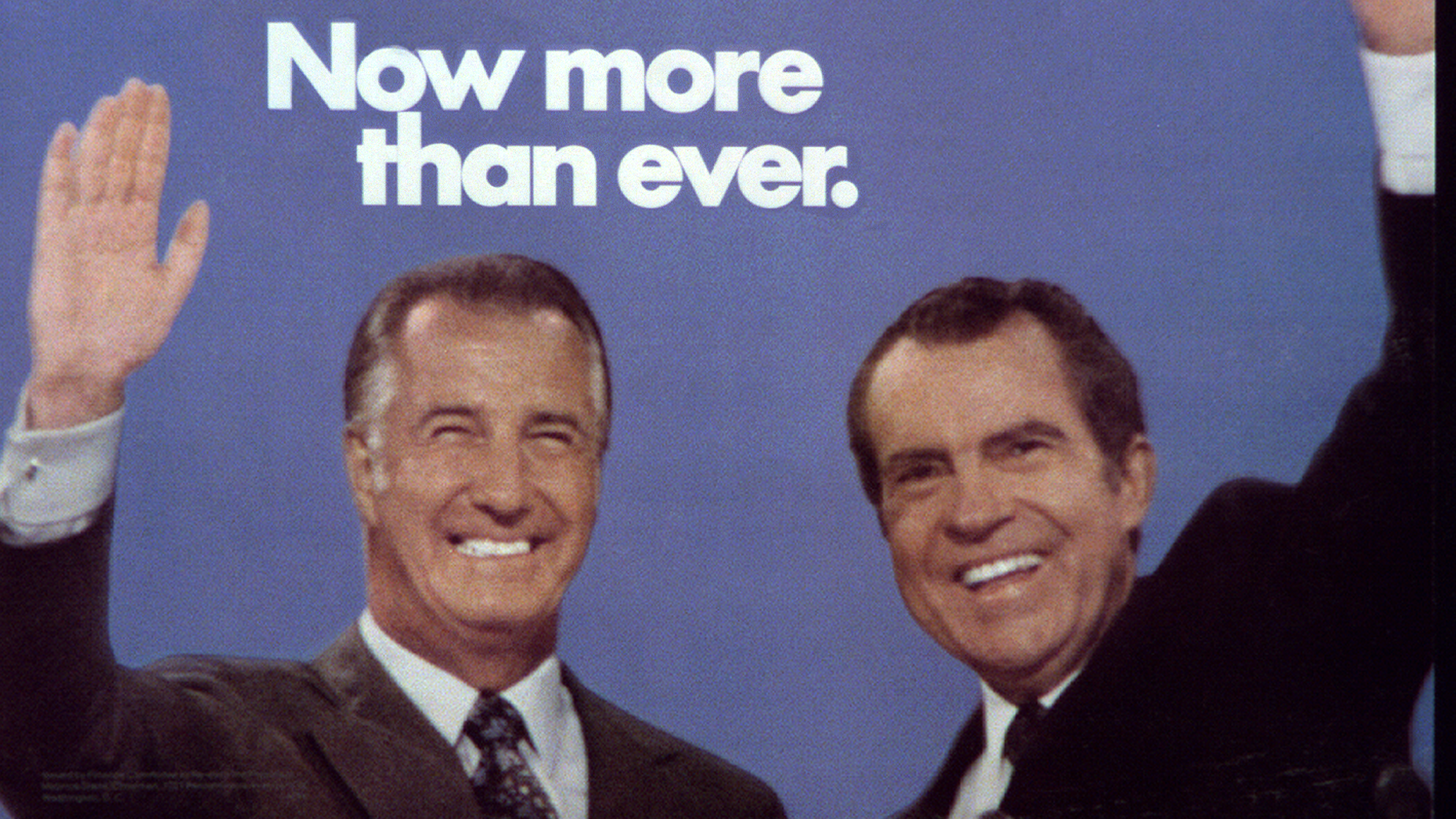

Richard Milhous Nixon was sworn in as President for the second time on January 20th, 1973. It was to be an eventful year: Roe v. Wade; Gravity’s Rainbow and Dark Side of the Moon; the Yom Kippur War and Arab oil embargo; the Saturday Night Massacre, when Nixon dismissed his Attorney General and then his Assistant Attorney General after they refused to fire Archibald Cox, Special Prosecutor in the Watergate investigation; a stock market decline that turned into a crash the next year, as Nixon’s resignation became inevitable.

It was also the year, by some accounts, that Nixon undermined forever America’s dominance in one of its key agricultural markets. Forty-five years later, a president is again tinkering with global markets, and there is the suggestion of an echo. Will there likewise be undesirable and unforeseen reverberations through the next decades?

One of the biggest concerns in that fretful time was inflation, which was really taking off despite price controls that had been in place since Nixon decoupled the dollar from gold in 1971. Agricultural commodities were particularly lively: after a disastrous crop failure in the Soviet Union, the world’s biggest grain producer, US farm prices had gone up about 19% in 1972 and the ascent seemed to be accelerating further in 1973. The dollar had been on a declining trajectory, and investors ran to commodities as a hedge, turning inflation into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Making matters worse, the Russians had cunningly outwitted Henry Kissinger in negotiating a three-year grain-purchase agreement to offset their agricultural misfortune and in an unexpected coup had bought the entire three-year allocation of the agreement upfront at US-government subsidized 1972 prices (two-thirds of which was bought with short-term credit from the US). This amounted to a quarter of the 1972-73 US wheat crop in addition to large quantities of soybeans and corn (so-called “feed grains”). (It later emerged that the Russians had resold a portion of these purchases at the higher 1973 prices; an indication, perhaps, of their latterly more obvious talent for capitalism). The press took to calling this deal “The Great Grain Robbery”. American consumers felt the pain: In the first six months of 1973, the prices of meat, poultry and fish were rising at an annual rate of 40%.

When prices rise for a sustained period, a chorus often swells up to claim that “this time is different.” That March of 1973 a Harvard-educated expert in grain economics worried in the New York Times that the “Days of ‘Cheap Food’ May Be Over”. He made a solid-seeming case. The Soviets were promising their people more food, and particularly more poultry and meat—which meant a disproportionate increase in grain consumption. (One pound of beef , pork or chicken requires respectively eight, four and 2 ½ pounds of feed). China, too, was making noises about feeding its vast population better, and, no doubt in a nod to Nixon’s famous 1972 visit, had recently started importing American wheat for the first time in 24 years. On the supply side, agricultural land in the US had become expensive, and the corporations which were increasingly dominating US farming would want a decent return on their investment, something that would obviously have to come from higher grain prices.

Nixon, as we later learned, was something of a control freak. While continually stressing that he was at heart strongly in favor of free markets, he had instituted “temporary” price controls in 1971. Alarmed by the inflation in crop prices he encouraged farmers to increase their plantings by revising the so-called set-aside programs (which limited the proportion of their acreage farmers could plant in exchange for government price guarantees and non-recourse loans). Given the price increases, the farmers needed little encouragement. In its March estimate, the USDA predicted that farmers would plant 17% more corn and 14 ½% more soybeans in 1973.

Trouble was, plants take time to grow and this didn’t solve the near-term problem.

Nixon was particularly worried about soybeans. The soybean is one of the main sources of vegetable protein (it contains about 44% by weight) and is widely used in animal feed. There was a particular squeeze on soybeans in 1973 not only from the Soviet purchases, but also because of an unusually harsh El Nino off Peru which had subverted its production of fish meal (basically dried anchovies)—one of soybean’s main competitors as a feed ingredient. Commodities traders were talking about a “global protein shortage.” By May, the July soybean contract had gone from $3.27 to $8.98.

Along with other crop prices, soybeans just kept going up. Critics, according to the New York Times, were contending that the White House’s preoccupation with the Watergate scandal had paralysed the Administration’s ability to cope. On June 13th President Nixon went on TV to address the American public. He began by stressing “what’s right in America”, referring to the economy as enjoying “one of the biggest, strongest booms in our history”. He went on to announce a number of anti-inflation measures, including another price freeze, on retail but not raw agricultural prices.

The next day, in a confused Chicago market, the July soybean contract rode a rollercoaster, sinking from the $11 close of the previous day to a low of $10, then recovering to a high of $11.70 before sinking again to close at $10.20. The pause didn’t last long. By June 22nd, the contract had almost touched $13, more than triple the price from a year previously. The USDA announced that the soybean supply would be down to about two weeks’ usage by September 1st and that “protein supplies are in a bind”. The agency requested a halt in trading on the soybean futures markets.

For the next week, pandemonium reigned. The rules on spot (cash) and futures prices were unclear. Farmers were reported to be destroying chickens and selling breeding sows because they were squeezed between feed prices and prices frozen at the supermarkets. Finally, after the close on the 27th, the Agriculture Secretary, Earl Butz, certified that if export orders were filled there would not be enough supply to meet domestic demand, thereby legally freeing the Commerce Department to announce that it would impose controls on exports of soybeans and cottonseed.

In Japan, this news was greeted with a mixture of shock, sadness and resolve. Around 92% of the three million tons of soybeans consumed annually in Japan came from the US. Soybeans were (and remain) a staple of the Japanese diet. Miso. Tofu. Soy sauce (240,000 tons of it every year). On top of recent fish contamination scandals, this news was very unwelcome. It was as if Americans had been forbidden hamburgers.

This was the third humiliation Japan had had to endure at the hands of Nixon, and they were not happy about it.

“We are really angry at Nixon‐san,” Hiroshi Higashimori, Secretary-General of the Japan Oilseed Processor Association, was quoted as saying.

It was thought that Nixon particularly had it in for Japan because he thought that its Prime Minister Sato had reneged on an agreement to reduce textile exports to the US. Despite Japan’s success at addressing US demands for a more even balance of trade, had determined to get his revenge. (Nixon was, as we know, a vindictive man famous for his “Enemies list”). The Japanese were insulted that Nixon hadn’t at least informed them before the August 1971 “Nixon Shokku” when he ended the dollar’s convertibility into gold, thereby blowing up the Bretton Woods exchange rate regime. Then, again without any consultation, Nixon famously visited and normalized relations with China, Japan’s historic foe, which was possibly the last nail in Sato’s political coffin. And now came the “Shoyu Shokku,” whereby the loyal and steadfast ally was to be deprived of miso, tofu and soy sauce.

Japan had long been concerned about its dependence on imports, and the US soybean embargo only added to a pre-existing resolve to address this vulnerability. Clearly, it had been rash to rely on a single point of failure for supplies of a staple food. The solution put forward by the monolithic Ministry of International Trade and Industry was “develop and import”. Japan’s plan was to increase its investments overseas strategically, from around $7bn a year to $25bn – $30bn by the decade’s end.

The soybean scare was over almost as soon as it had begun, but the effects persisted and indeed, still persist. Japan responded by investing massively in Brazil. In 1973, Brazil was producing about five million tons of soybeans per year, most of it for domestic consumption, while the US was effectively a monopolist in soybean exports. Ten years later, Brazil was producing 15 million tons. Because of greater land availability, its costs were and continue to be significantly below those in the US. The USDA is currently projecting Brazilian production in 2019 at about 119 million tons, roughly equal with that of the US. Because US consumption is higher, however, Brazil has effectively become the largest exporter of soybeans in the world.

Whether those who draw parallels with our current Administration’s use of trade weapons are correct, who is to say? Given the expansion of the world population and the increased popularity of meat, it seems unlikely that the US could have continued to be the world’s sole supplier, even having more than tripled its own production since 1973. Still, the echo is perhaps worth listening for.

The fate of Brazil’s rain forests is a topic for another day.