Singaporeans are often reminded that ours is a small, vulnerable nation-state, surrounded by bigger neighbours who might turn hostile; we’re told our country might be targeted by terrorists. “Not If, But When,” warn posters at subway stations and bus stops, alerting Singaporeans of not only the danger, but the inevitability, of terrorist attacks. Singapore is small, rich, successful—there are many who covet our success, we’re told. Ours is a society on permanent alert, always attuned to potential threats to our wealth or comfort.

In late July every year, national flags begin to appear all over Singapore. The red-and-white rectangles, with their five white stars and crescent moon, fly from poles, hang from windows, and adorn balconies. It’s all in preparation for Singapore’s National Day on the 9th of August—the anniversary of the day our tiny island nation left the far bigger Federation of Malaysia in 1965 to strike out on our own. Since then, we’ve had a parade every year, at its heart a military display to warn foreigners that we aren’t to be pushed around.

In 1966, Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, said that to survive in a world where the big fish eat the small, Singapore must become a “poisonous shrimp,” meaning that anyone who tries to hurt the country would pay a heavy price.

In this siege environment, I—like others who are critical of the politics, democracy, social justice and human rights in Singapore—am reckoned by many to be a traitor to my country.

A tiny island nation of just under six million, my country takes pride in “punching above our weight,” high in international rankings from PISA scores to per capita GDP. Singaporeans are used to hearing visitors gush about how lovely our country is, and how the airport is such a delight (to be fair, Changi Airport is pretty awesome).

It’s easy to understand the urge to preserve this glowing image. But while Singapore does have a lot to be proud of, it has a much less stellar record when it comes to political freedom, civil liberties, and human rights. The country hasn’t had a change in government since the People’s Action Party (more commonly known as the PAP) was voted into power in 1959—partly because the party has managed to deliver economic development and success, but also because, during its half century in power, the political landscape has been skewed in the incumbent party’s favour.

At various times the PAP’s political opponents have been detained without trial, sued, bankrupted, jailed, intimidated and subjected to smear campaigns in the press. Alternative parties grapple with gerrymandering, as well, and with an official campaigning period of just nine days between Nomination Day and Polling Day. Out of a hundred seats in Parliament, nine are held by the opposition Workers’ Party, alongside nine non-partisan appointment members. The PAP holds all the other seats.

And civil society isn’t faring much better. While freedom of expression and assembly are guaranteed under the Constitution, subsequent laws have curtailed these rights to a ludicrous degree. Under the Public Order Act introduced in 2009, even a single person can constitute an illegal assembly. In 2018, performance artist Seelan Palay ended up spending two weeks behind bars after refusing to pay a S$2,500 fine for participating in an “illegal procession”—namely, a performance in which he walked, alone, to Parliament House, carrying a mirror. He was arrested while standing outside the building in silence.

Public discourse is similarly constrained: self-censorship is rife, because people are worried about the consequences of speaking out. Laws like the Sedition Act, and Section 298 of the Singapore Penal Code—which criminalises speech with the “deliberate intent to wound the religious or racial feelings of any person”—imperil discussions of race and religion. The Administration of Justice (Protection) Act was first used against an activist and opposition politician for Facebook posts authorities claimed had “scandalised the judiciary.” Add to this the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), passed in Parliament in May of this year. Once in force, the law will allow any government minister to order, “in the public interest,” “corrections,” removal, or the blocking of access to online content, based on their own assessment of anything online that might be “false or misleading.”

In addition to these issues, I also campaign for the abolition of capital punishment in Singapore, where long-drop hanging is the ultimate penalty for offences like drug trafficking, murder, and firearms trafficking. Possession of as little as 500g of cannabis could potentially result in a death sentence.

Instead of bolstering Singapore’s international image, I’m often accused of tearing it down, “talking bad” about our country to outsiders, airing our dirty laundry. I don’t love my country, according to these people; I just want to “see it burn.”

But what I would like to see is a Singapore in which people are empowered to participate in politics and causes that they care about (even, or especially, the politically sensitive ones), and to criticise or resist publicly without fear, should the need arise. I want us to have open conversations about complex, controversial issues, without having the government step in to dictate the terms or shut things down. I want to see a Singapore that doesn’t prioritise economy and wealth as the main indicators of success, but emphasises dignity and well-being for all its people.

As an undergraduate studying abroad in the late 2000s, I would bristle and become defensive if anyone even suggested to me that Singapore wasn’t a democracy. It seemed an outrageous insult; how could my country, as advanced and developed and prosperous as any in the world, not be a democracy? Yet if you’d asked me as an 18-year-old to discuss elections in Singapore, I wouldn’t have been able to point to a single example. Up until the 2011 general election, there hadn’t been a vote in the constituency I grew up in for over a decade, simply because there was no opposition party contesting that area. At that age, I wouldn’t have been able to engage in conversation about civil liberties or human rights, either. I would have insisted—wrongly—that there was no such thing as homelessness in Singapore.

My own teenage ignorance mirrors conversations I’ve had since then with Singaporeans, both young and old. People have confidently told me that the PAP government has never abused power (it has, and even the prime minister’s own siblings say so), that there are adequate checks and balances in the system (fairly often, there aren’t), and that one can simply trust the government to do whatever they think they need to (uh-oh).

Without an understanding of our own history and political reality, it’s difficult to participate in democratic processes as full citizens, because we simply lack knowledge of the context within which we can, and should, exercise our political rights. That’s why it isn’t enough to just hear about the good stuff; we need to know more about the problems too. It’s only when we’re aware of, and talk extensively about, the flaws and cracks in our system that we can work on fixing them.

It’s also important for the international community to be aware of this less “shiny” side of Singapore. Given its stellar reputation, the city-state is often seen as a model that other countries can aspire to. I’ve seen Singapore name-checked as inspiration all over, from Southeast Asian neighbours like the Philippines and Myanmar to countries in Europe and as far away as Latin America. But when I speak to people from these countries, very few know about the deeper context that would make replicating the “Singapore model” either impossible, or undesirable.

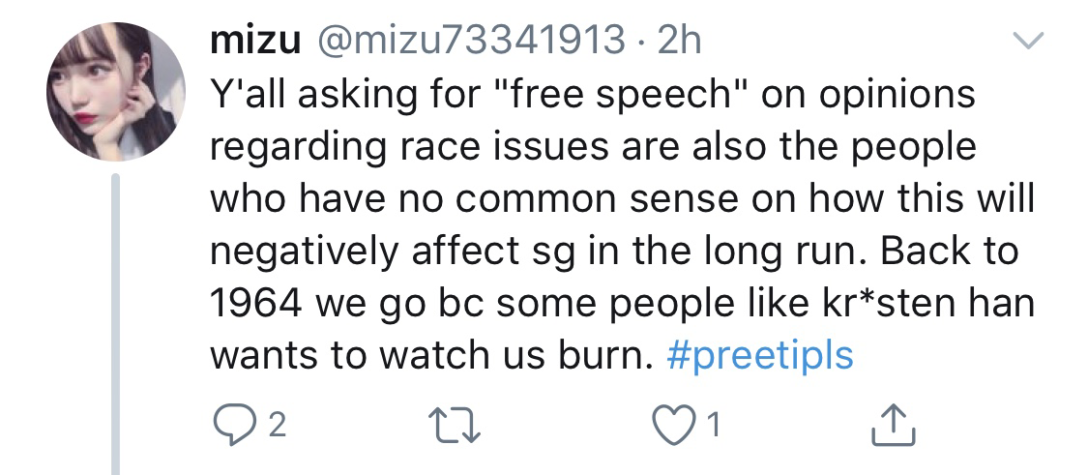

screenshot provided by the author

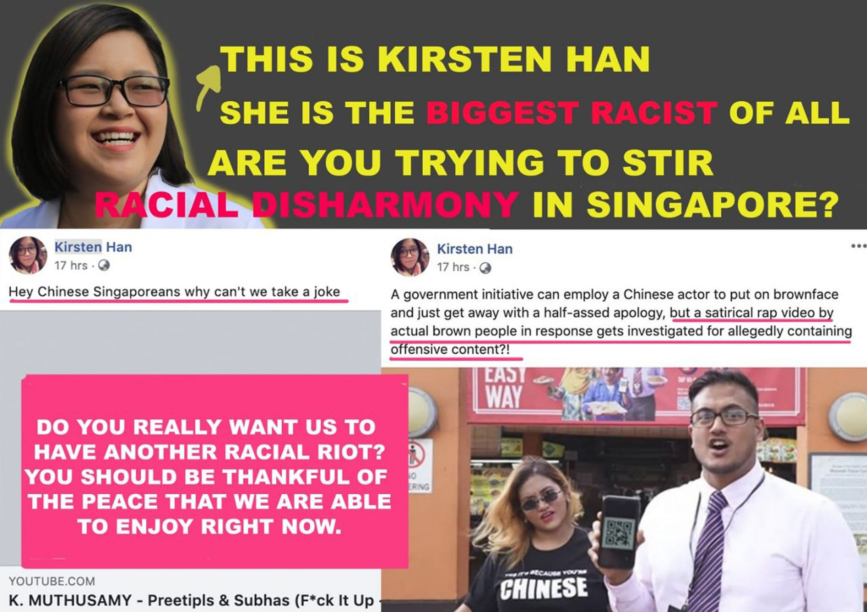

screenshot provided by the authorA social media scandal erupted recently on Instagram and Twitter, drawing attention to an ad campaign for E-Pay, a new nationwide e-payment system. The campaign featured Dennis Chew, a Chinese Singaporean actor known for his comedic alter-ego Auntie Lucy, a middle-aged Chinese woman he plays in drag. In this campaign, though, Chew was photographed as four different generic characters from Singapore’s main ethnic groups, including a Malay woman in a tudung (the Malay word for hijab). He also darkened his skin to portray an Indian office worker with a lanyard that read “K Muthusamy.”

Singapore is a country that prides, and promotes, itself on its racial and religious harmony. While the Chinese make up about 76% of the population, Malays and Indians are at about 15% and 7.5% respectively—a long-established ethnic mix. But this wasn’t Singapore’s first encounter with brownface. In fact, there have been multiple cases over the past decade, and this latest ad campaign followed a well-trodden path: after the outrage online, the agencies behind the campaign apologised for any hurt that had been unintentionally caused, removed the ad, and sought to move on.

Enter YouTube star Preetipls and rapper Subhas Nair. The siblings released a defiant, angry parody of Iggy Azalea and Kash Doll’s song “Fuck It Up”, mocking racist Chinese Singaporeans who “keep fucking it up” (“How come you so jealous / of the colour of my skin? Wait, actually it’s accurate of the city we in / No matter who we choose / the Chinese man win.”)

screenshot provided by the author

screenshot provided by the authorIndian Singaporeans like Preeti and Subhas have reason to be upset. Singaporeans from ethnic minority groups already live in a context where a government minister can say openly that the country is “not ready” for anyone who isn’t Chinese to become the Prime Minister (even though Singaporeans said they would like his Indian Singaporean colleague to take the top spot); where it’s legal for rental ads to say “No Indians No PRCs [referring to immigrants from the People’s Republic of China]”; where there is both historic and ongoing discrimination against Malays when it comes to military conscription; where surveys find that there’s been a rise in perceived workplace discrimination among Malay and Indian Singaporeans.

When the hammer came down, though, it came down on those with less power. Instead of tackling the use of brownface in a nationwide ad campaign—put together by established creative agencies, including the talent agency arm of Singapore’s national broadcaster MediaCorp—the police opened an investigation into the parody rap video.

“This rap video insults Chinese Singaporeans and uses four-letter words about Chinese Singaporeans, vulgar gestures—pointing of middle fingers—to make minorities angry with Chinese Singaporeans,” said Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam.

“If we allow this, then we have to allow other videos,” he continued. “You allow one, you have to allow a hundred. What do you think will happen to our racial harmony, social fabric; how will people look at each other?”

The sibling artists and their supporters were presented as being cavalier about Singapore’s fragile race relations, or even actively seeking to foment social unrest. Overnight, memes began popping up social media platforms and forums. Among these were memes claiming that I personally was the “biggest racist” who wanted to “stir racial riots in Singapore” and for the country to “boil over into protest & riots day & nite as in Hong Kong.”

The comments against the Nair siblings were even worse, especially since they also came from the state: The Ministry of Home Affairs accused them of expressing “racist sentiments” and writing lyrics that were “blatantly false”.

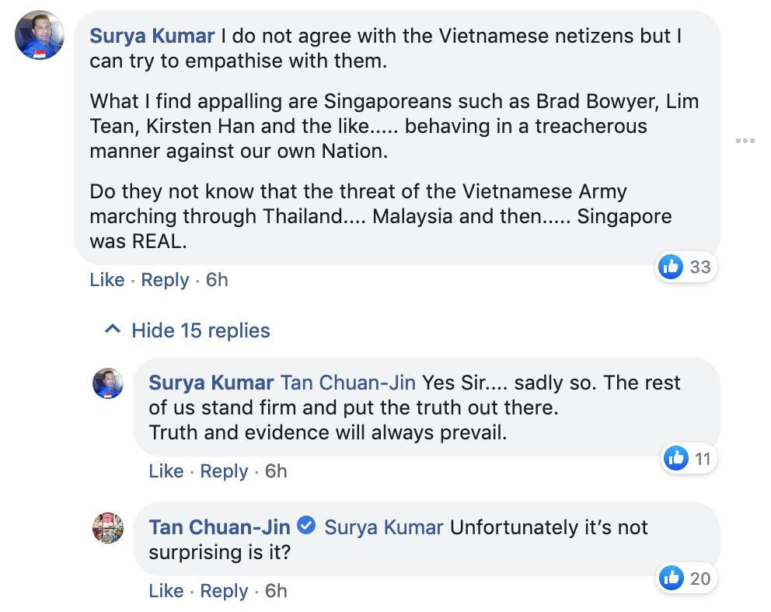

screenshot provided by the author

screenshot provided by the authorTaking every criticism as an affront, and insisting that everything is already awesome, inevitably protects those in power, since a defence of the status quo is also a defence of the system over which they preside. This toxic patriotism allows authoritarian politicians to conflate their own party, even their own personalities, with the idea of the nation, making criticism of their rule seem like a direct attack on the nation itself. Dissent is no longer treated as part of a healthy culture of debate, but as evidence of treason and treachery. In this climate, only acquiescence and applause can be tolerated. Public discourse suffers, but no authoritarian who ever rose to power ever really cared about discourse—only domination.

My country’s government, dominated by the PAP, hasn’t outright called me a traitor (yet). But they’ve heavily implied it, and they’ve not had a problem with others pointing the finger.

screenshot provided by the author

screenshot provided by the author“What I find appalling are Singaporeans such as Brad Bowyer, Lim Tean [both opposition politicians], Kirsten Han and the like….. behaving in a treacherous manner against our own Nation,” a commenter wrote below a Facebook post by Tan Chuan-Jin, Singapore’s Speaker of Parliament.

“Unfortunately it’s not surprising is it?” was the Speaker’s reply.

He left it at that, but the signal was clear. In instances where my fellow citizens accuse me of treason, I will receive no defence from members of a government that is still meant to be representing me, regardless of our political differences.

This it isn’t unique to my country, either; journalists and activists living and working under authoritarian regimes the world over have been subjected to this “special treatment”. On the sidelines of journalism conferences, there’ve been times when I was jokingly introduced to someone new as “a traitor”, only to hear them say, “oh yes, me too.”

How else is one to cope and keep pressing on in the face of these absurd situations? Accepting our supposed status as “traitors” has become a necessary component of journalistic work in many countries—but it shouldn’t be. When someone is passionate enough to take a stand for justice, or committed enough to speak truth to power, it’s ludicrous to treat them as threats to society. It’s even dangerous to do so, not just for the person targeted, but for the world.