Satyajit Ray was perhaps the most consequential South Asian artist of the twentieth century. He is remembered foremost as a filmmaker. Championed abroad as India’s first true auteur, his works—from the debut Pather Panchali (1955), the first of the celebrated ‘Apu Trilogy’—are enshrined in the canons of world cinema. In addition to filmmaking, Ray was a prolific graphic designer, fiction writer, publisher, critic, and musician. Also, he was very tall.

So tall was Ray, wrote biographer Marie Seton, that he rose “taller than any of the tall Ray ancestors, who had for generations been noted as a generally tall family.” Nor did Ray “stop growing until he reached six feet four and a half inches,” which made him, suggests Seton, “one of the tallest, if not the tallest, living Bengali.” The poet and Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, is said to have dedicated a poem to the infant Ray likening him to a drop of dew. When the Japanese film curator Kashiko Kawakita first met Ray, she was dazzled by his physical presence—an experience she analogizes to meeting a “Hindu god.” She also compares Ray to a tree.

In 1987, the Tajik filmmaker, Davlat Khudonazarov, travelled from the Soviet Union to India for the “sole purpose” of meeting the man he regarded as his hero and ustad. While chairman of the USSR Union of Cinematographers, Khudonazarov had viewed Ray’s films in Bengali, without subtitles—and yet felt he had understood “everything down to the last nuance.” Preparing for his trip to Kolkata, he was mindful of the rumour of Ray’s colossal height. Remembering the momentous occasion, Khudonazarov recalled: “Just as a Muslim visits Mecca, I wanted to pay my respects to Ray. Knowing him to be extremely tall, I took with me, as a present to him, the largest Tajik robe I could find. Even that turned out to be too small for the towering figure of Indian cinema.”

Without having done precise calculations, I would wager two-thirds of all print media about Ray—profiles, interviews, and in-depth analyses—in British and American print from the 1950s and 1960s expressed, in one form or another, sheer bewilderment at the director’s height. Big rangy Calcuttan were real words printed in the New York Times. They appeared in Howard Thompson’s 1958 interview with Ray, in which Thompson repeatedly stressed Ray’s surprising physicality: behold, not a “dreaming dilettante” or a “mystic Oriental,” but a “strapping, swarthy chap, with strong features.” James Blue’s 1968 interview with Ray for Film Comment introduces the filmmaker with all the salient and vital facts of journalism: “tall man, over six-feet-one, enormous for an Indian.” In Edward Gargan’s 1992 article on Ray’s twilight years, a more subtle yet nevertheless astonished physical description appears: Ray was “a tall, lanky man who looks a bit like the silent, gaunt statues on Easter Island.” In other words, Western publications indulged in writing about Ray as a physiognomic curiosity. Their encounters with Ray’s actual body resulted in a discernable style of writing and gaze that expressed, at best, a kind of overfamiliarity with the director and, at worst, exaggeratedly colourful and exoticized renderings of Ray as a sort of uniquely racialized spectacle.

Despite the vantage or politics of one’s gaze, most people nevertheless looked upon Ray and agreed: he was a very tall man. Formally speaking, both gaze and speech were forced to adjust: one must look upward and brace for his bellowing baritone. Yet the physical trait that made him exceptional also made him familiar. Friends, colleagues, and loved ones spotted him in a crowd all the more easily; they recognized him all the more affectionately. Madhabi Mukherjee, the great Ray heroine, recalls the moment she first saw Ray: a flash of recognition at a funeral when, suddenly, she noticed “a very tall man taking photographs from under a tree.”

Those who frequented his regular haunts would fondly remember this aspect of Ray’s presence, as did those in the Oxford Bookstore on Park Street in Kolkata, who recalled how he would regularly visit to buy notebooks; indeed all of his Feluda stories were written in those very notebooks. “[When] the tall, lanky 6’4” Ray would walk into the store, the routine was familiar.” In other words, for the intimates in Ray’s life, his height was not an animal curiosity—as it may have been for the New York Times—rather it was a token of his identity, as exceptional and incongruous as it was familiar.

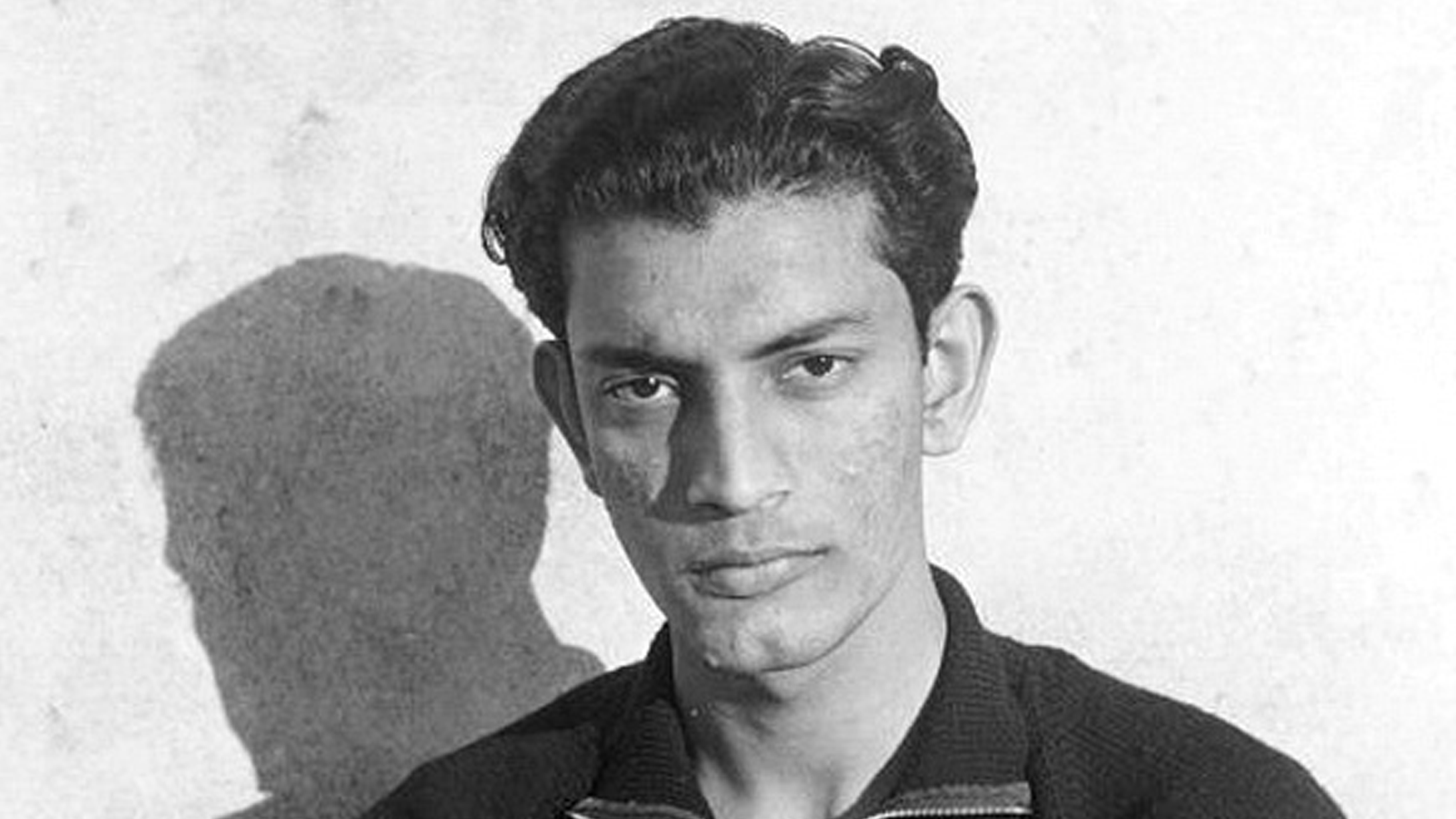

In a 1967 documentary by the Canadian filmmaker, James Beveridge, we become close witnesses to Ray’s Himaylan presence: lounging, arm extended over the back of an empty car seat; reclining on a divan, commenting on his music and illustrations; or simply half-lying on the floor. He strides through the market, the film set, the village road. He occupies space with a tremendous and instinctive sense of repose; a deep, glacial assurance in each gesture. These characteristics are captured too in photographs of the filmmaker, including those by his lifelong friend and de facto biographer, Nemai Ghosh. A visual regime is discernible in portraits of Ray: angles from below, verticalizing shapes and props; a strategic emphasis on stature and the statuesque.

What were Ray’s own feelings about his height? What was it like up there? This question is more difficult to gauge. When directing Pather Panchali, he and his crew would take the bus from the city to the village to shoot on weekends. When filled with commuters, it is said that Ray had to lean out the door of the bus to keep his head from hitting the ceiling.

One potential window into Ray’s tall man phenomenology may lie in the fact that his height was mirrored by his fictional detective hero, Feluda. In Sonar Kella, Feluda is asked by an inquiring pulp fiction author, Lalmohan Ganguli, about his height. “Nearly six feet,” Feluda replies. The pulp author is thrilled: “Oh, that’s a very good height, the same as my hero’s”—this pulp hero having been physically modeled after “advertisements of Charles Atlas in British magazines.” A fantasia of masculine corporeality follows: Ganguli’s hero is fashioned as one “standing proudly, his chest and all his muscles expanded, his hands on his waist,” “a lion,” “not even an ounce of fat on his body,” and “muscles [that] rippled like waves.”

A fantasy indeed, for, as Ganguli puts it: “In Bengal, that kind of thing is impossible.”

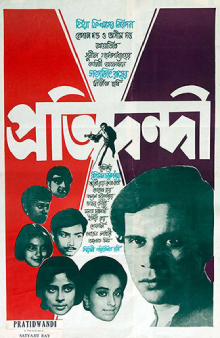

A telling aspect of this exchange is the structuring presence of race—namely, the shared in-joke that Bengali men have none of the hero’s imposing physical qualities (least of all height). In the distressing waiting-room of a job interview in Pratidwandi (1970), a group of anxious college graduates are demoralized by the confident entry of one of the candidates: “The job is his for sure!” “How tall is he?” “Has to be around six feet.” “Don’t worry—they might prefer shorter ones here.”

Though an in-joke, the trope of the ‘short Bengali’ is also a stereotype of colonial pedigree. Historians like Mrinalini Sinha have argued that colonial legislature and the articulation of a theory of ‘martial races’—a racial classification system that structured military enlistment in British India—consolidated the particular idea of Bengalis as essentially ‘effeminate’ in comparison with other races, e.g. the ‘manly Englishman.’ At the same time, it was not by coincidence that a system of British eugenic ideology kept Bengalis away from military arms and training. Peter Heehs, Michael Silvestri and other historians have examined the anxieties of British administrators concerning the growing specter of ‘Bengali terrorism’, drawing parallels with the Sinn Féin and Russian anarchists, defining Bengalis “of all Indians” as the most prone to anti-colonial terrorism.

We might consider that Ray, through Feluda, satirizes not only the masculinist fantasy of pulp fiction writing, but also the embarrassed sensitivity (if not outright mortification) at being the tall man out.

To my mind, Ray’s height is one of those rare incidents of cosmic appropriateness. How perfectly suitable and apt for a soaring artistic spirit to embody a like physical stature. Ray passed away in 1992—after Ritwik Ghatak in 1976, and prior to Mrinal Sen in 2018. With their departures, one feels the proverbial golden age of the Bengali cinema to have passed, too, into an irreversible form of silence. Such an era only lives on in the images it has left us, and whatever memories of epoch we have been able to salvage from them—however minute or eccentric they may be.

That Ray, one of the great artists of his century, was indeed as tall as mythology dictates is only just. Ray was as strained a metaphor, as striking a reminder as there ever was in our cinema of the Biblical prophets: near-supernatural beings and truth-tellers who lived closer to the time of Creation, interpreters of dreams who saw the living whole more clearly, who were said to live hundreds of years longer than contemporary humans, and who stood as tall as cedars.

AP/Jim Pringle

AP/Jim Pringle