The Christianization of Russia was the result of a political deal between the Prince of Novgorod, now known as Vladimir the Great, and the Byzantine Emperor Basil II. When an internal uprising threatened Constantinople in 987, Basil sought military assistance from the Rus, whose empire, reaching from Belarus, Russia and Ukraine to the Baltic Sea, Vladimir had consolidated and fortified; from his recent conquest of Cherson (not to be confused with its namesake, modern Kherson), Vladimir himself posed a direct threat to Constantinople. In exchange for marriage to Basil’s sister, the Byzantine Princess Anna, Vladimir agreed to accept Christian baptism, and to spread the faith among his own people—also, to send an army of 6,000 to quash the revolt, and to return Cherson to Byzantium. Historians appear to be somewhat uncertain on the question of whether this deal was an alliance, or more like a shakedown.

It bears mentioning that in the twilight of paganism, Vladimir had been shopping for a monotheistic religion, and sent envoys around to review the various options. As legend goes, Vladimir rejected Islam specifically because circumcision, and bans on pork and booze, would never work for his people, observing that “Drinking is the joy of the Rus”. The gothic punishment-focused bleakness of Germany proved too depressing even for the Slavs. But the gorgeous architecture and decoration of the temples in Constantinople and the stateliness of worship there were enough to bring his court to its knees. “We no longer knew whether we were in heaven or on earth,” they reported, according to the Primary Chronicle, “nor such beauty, and we know not how to tell of it.”

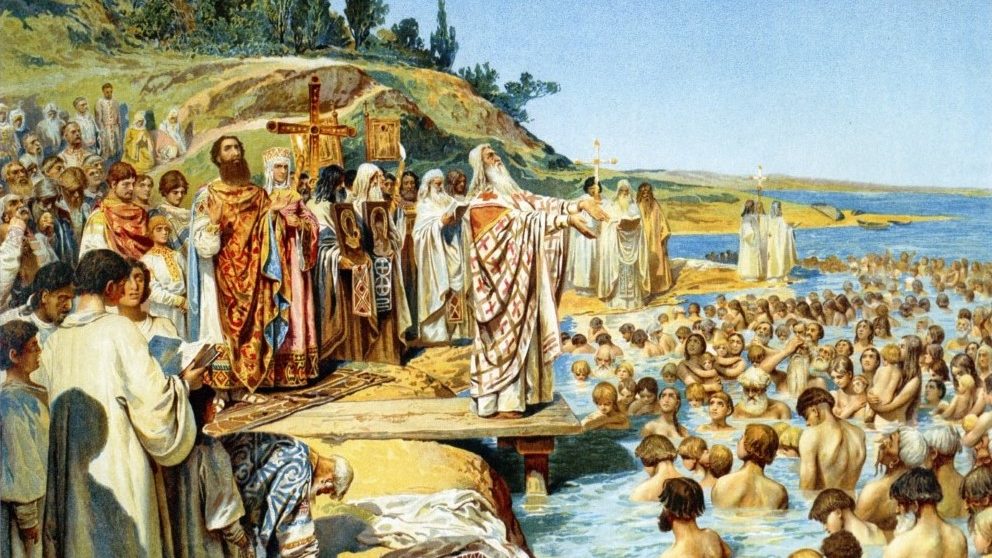

Having secured his military, political, religious and matrimonial objectives, Vladimir returned in triumph to Kyiv (bearing with him, according to Gibbon, the brazen gates of Cherson, and erecting them before the first church “as a trophy of his victory and faith”), and commenced to baptize his own people en masse in the Dnieper River, a historic event revered as the birth of Slavic Christianity.

In the centuries after the Crusades, the capital of Eastern Christianity fell to various kingdoms. Though the Ukrainian church won a brief period of independence from Moscow after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Stalin stamped it out in the 1930s, permitting only the Russian church to survive as the de facto Christian authority in the Soviet Union.

A thousand years after the baptism of Vladimir the Great, a great celebration of Slavic Christianity in Ukraine and Russia dovetailed neatly with the decline of the Soviet Union; the Berlin Wall would fall the following year. By then, the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) had long since gained control of the majority of Eastern Orthodox congregants.

Soviet citizens, oppressed by the increasingly demoralizing failures of the USSR, returned to the comforts of old-timey religion. Churches and monasteries previously seized under the state-mandated policy of atheism were restored to church control, among them the 13th-century Danilov Monastery in Moscow, the crown jewel of Russian Christianity, in 1983.

The celebrations of 1988 signaled a significant public move in the Russian state’s longterm reengagement with the church as a tool of empire. From the standpoint of the collapsing KGB, the church would stoke Russian solidarity in the inevitable independent states that would follow; it would keep communications flowing between the Russian government and its former territories, both as a source of information and a propaganda engine. As in the MacArthur plan after the fall of the Japanese Empire, the churches would also serve as a source of national pride and history, to help recover the morale of a beaten population. This plan, though effective, gave rise to an uneasy tension between church and state, particularly with respect to Ukraine. Which authority—whether political, ecclesiastic, or both—would control the birthplace of Slavic Christianity?

Less than a decade after the millennial celebration, on July 18, 1995, more than a thousand mourners, guarded by a group that included far-right Ukrainian nationalists, were prevented by riot police from burying the head of the schismatic Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Volodymyr (Romaniuk), at the Cathedral of St. Sofia in Kyiv. An unholy stew of political, nationalist and religious strife surrounding the patriarch’s sudden and mysterious death suggested any number of causes for the violence, which left two dead. Because Orthodox burial rules require that a funeral be completed before sundown, mourners tore up the sidewalk in front of the cathedral to bury the patriarch, where his grave remains, a reminder of intractable religious and political discord.

At the center of this confrontation was a big problem by the name of Patriarch Filaret, the former Metropolitan (or, primary authority) of Kyiv in the Russian Orthodox Church. Filaret, a calculating and powerful authoritarian figure, had repeatedly and fruitlessly petitioned the ROC to grant autocephaly—the right of self-governance—to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. The ROC defrocked him for insubordination, cruelty, oath-breaking etc. in 1992, ushering in a period of increasing factionalism.

In December of 2018, after years of infighting, the Ukrainian Orthodox church was at last granted autocephaly by the synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, a governing body of twelve hierarchs from around the world serving under the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew I, who is the spiritual leader of the world’s Orthodox Christians. The Orthodox Church of Ukraine, formed and recognized in Kyiv, was a sort of Cerberus of faiths, with three separate denominations vowing unity in exchange for self-determination and independence from Moscow.

It’s not too much to say that the long-sought independence of the Ukrainian church is one of the deepest and most powerful currents in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. A church operating under its own auspices is a church that will no longer be taking its orders from Moscow. Vladimir Putin vocally denounced the decision; the Ukrainian parliament passed laws requiring churches still affiliated with Russia to publicly identify themselves as such.

Unsurprisingly, the war against Ukraine has intensified this split. In late March, a bill banning the Moscow Patriarchate from Ukraine was sent to its parliament for consideration, as once-blurred lines between political and religious loyalties now necessitate a crystal-clear focus. Earlier that month, for example, Ukrainian soldiers at a military airstrip searching for the source of a laser pointer reportedly found a stockpile of food and some weapons in a church operated by monks still loyal to Moscow.

Tens of millions of Orthodox Christians live in the NATO member states: Greece, Romania, Bulgaria and Montenegro. And decades-long sectarian struggles have not been limited to Russia and Ukraine. North Macedonia’s church declared its autocephaly in 1967, and was denied by the Serbian church, when both were still part of Yugoslavia; it was only last Tuesday that the patriarchs of North Macedonia and Serbia joined to announce Serbia’s acceptance of North Macedonian autocephaly. Taken as a whole, the Orthodox Christian church is many-layered in its complexity, with countless overlapping political and religious loyalties.

On the occasion of Orthodox Easter, major articles in the New York Times, Washington Post, and elsewhere framed the schism in Eastern Orthodoxy exclusively with respect to Kirill’s and Putin’s actions and their damage to the church. Far less has been said about the long-brewing political and religious rupture between Ukraine and Russia that burst forth with the newly autocephalous Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

The cradle of Slavic Christianity is in Kyiv, where Vladimir the Great held a mass baptism on the shores of the Dneiper River more than a thousand years ago, a fact that can be exploited all too easily by political opportunists. The power that a holy site holds over believers predates all maps, all politics, all modern allegiances. When monsters like Vladimir Putin get hold of them, great evil can result.

During the annexation of Crimea in 2014, ROC Metropolitan Kirill refused to appear with Putin before congress to give the church’s seal of approval, allegedly fearing the creation of a permanent schism in Eastern Orthodoxy as a whole. Now that the Orthodox Church of Ukraine has been formed, with the blessing of Western forces, Kirill is in full crusader mode, helping to support Putin’s hallucinatory fantasies of reclaiming the glory of the Rus people. From this perspective, support for the war against Ukraine among the Russian people takes on a different color. To what degree do the estimated 90 million members of the Russian Orthodox Church—the largest autocephalous church in the Orthodox Christian world—believe in the natural unity of Kyiv and Moscow, not for political reasons, but based on their religious convictions?

Casey Taylor is a writer and product manufactured in southwestern Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Other writing can be found here.