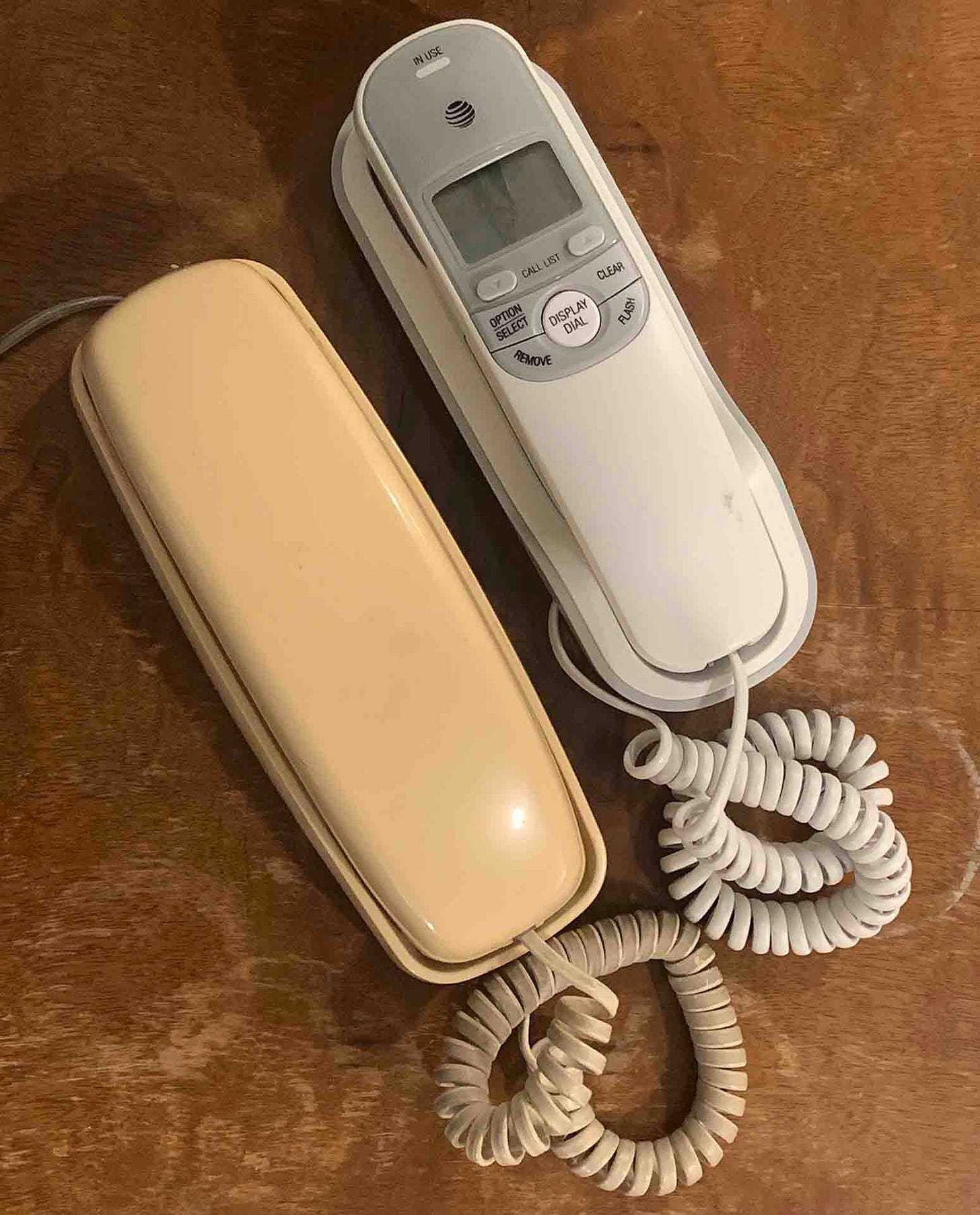

I BOUGHT THIS telephone, but I can find no record of when or where. Amazon tells me I had bought an AT&T 201M Trimline phone in July 2012, and I know this phone was a replacement for that phone. I have an impression in my mind that I bought it in a mom-and-pop hardware store on 72nd Street, on a trip to load up on practical and useful things. It’s the store where I bought our chrome napkin holder and a mostly decent collapsible clothes-drying rack.

The TR1909 Trimline was not decent or practical or useful. It was, at first, an improvement over the 201M Trimline, which was busted. I think by the end of its not very long life it had a rattle or stutter in its ringer and something similar going on in its earpiece. The new TR1909 did ring when someone called it (at first), and you could hear the other person reasonably well through the earpiece.

At least, I could hear that other person until I really settled in to talk, cradling the phone more tightly between my shoulder and my ear. That was when the hang-up button, sticking up high and prominent from the slim and tapering body of the handset, would bump against my cheekbone and cut off the call.

Why did I own a corded landline telephone at all? It was a necessity, I would have said. The corded phone had always been a piece of the standard reporter’s toolkit, the next best thing to talking to someone face to face. You could really hear them, and they could really hear you. Cordless phones delivered attenuated sound and dropped words; cell phones sounded even worse and would drop the whole call. The corded phone gave you a solid, physical connection.

I had a whole analog setup that went with it, too: a cassette recorder, a gizmo that you plugged the handset cord into to feed the sound into the cassette recorder’s microphone jack, a transcribing machine with a foot pedal to wind the finished cassette back and forth while typing it up. All of this equipment rested on the old-fashioned integrity of the telephone itself.

But the telephone stunk. The TR1909 Trimline was light and flimsy, its cradle part always in danger of flying off the desk. When it hit the floor, a wedge-shaped piece of the base that kept it sitting flat would come unclipped, or the four double-A batteries that powered the never-consulted caller I.D. would spill out. Even attached to a copper wire—feeding, by now, into a phone jack carrying a digital signal from an internet service provider—it seemed hopelessly insecure.

Meanwhile, for reporting, digital transcribing services had taken over. I could set my cell phone on my desk in speakerphone mode, hit record on my laptop, and have a searchable transcript of the m4a file, synced to the audio, minutes after hanging up. Sure, the source and I were yelling at each other in a flattened and tinny aural space, but everyone’s used to that by now. I’m not sure where I’d find all my phone-recording gadgets and attachments right now, even if I wanted to use them.

Really, I had the phone because I didn’t want to let go of the 20th century telephone experience. The truth was, though, the TR1909 Trimline was the physical-object equivalent of making a 21st century mobile-phone call: a degraded and unreliable shadow of the real thing. When we moved to our new apartment, it took weeks for me to figure out that our old and new service providers had fumbled the handoff of our landline number, and that incoming calls were going into the void.

After I got the phone number situation straightened back out, the landline attached to the Trimline was basically for calling my mom, and for fielding calls from “cardholder services” robots or overseas boiler-room guys trying to convince me that Customs and Border Protection had intercepted a package of mine. Then one night my mom called my cell phone. I hadn’t answered the landline, she said.

This was, I realized, because the ringer on the landline had stopped working. I tried searching online for new landlines and got the 201M. “Last purchased Jul 6 2012,” Amazon said, in an automatically generated inadvertent warning.

All I wanted, I complained to an expert shopper friend, was a normal, no-frills telephone like everyone had in the ’90s. She suggested I should just get one from the ’90s, then.

Why not? When everything new is junk, why not buy old junk? I took my search to eBay, scrolling through phones I would have taken for granted three decades ago: aqua, burnt orange, sage green. Cracked phones; “untested-as-is” phones; fully restored phones, for which the standard price seemed to be $125. I settled on a Trimline, tested but not restored, in a sort of pantyhose color, an unremarkable beige-y peach that someone might have sold as “millennial pink” in the new millennium.

The new-old phone arrived repacked in its original box. It was a Trimline 201, but it was about half a pound heavier than Amazon’s listed weight for a contemporary Trimline 201M—and nearly twice the weight of the TR1909 (with three out of four batteries). When I set it down, it stayed put. A sticker on the bottom read 09/04/89: the Labor Day before my first semester of college; the release date of Einstürzende Neubauten’s Haus der Lüge.

A day or two later it rang, with a dense, familiar, burbling ring, a ring out of the bygone past. I hefted the receiver. It was a spam call.

Thank you for reading POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!