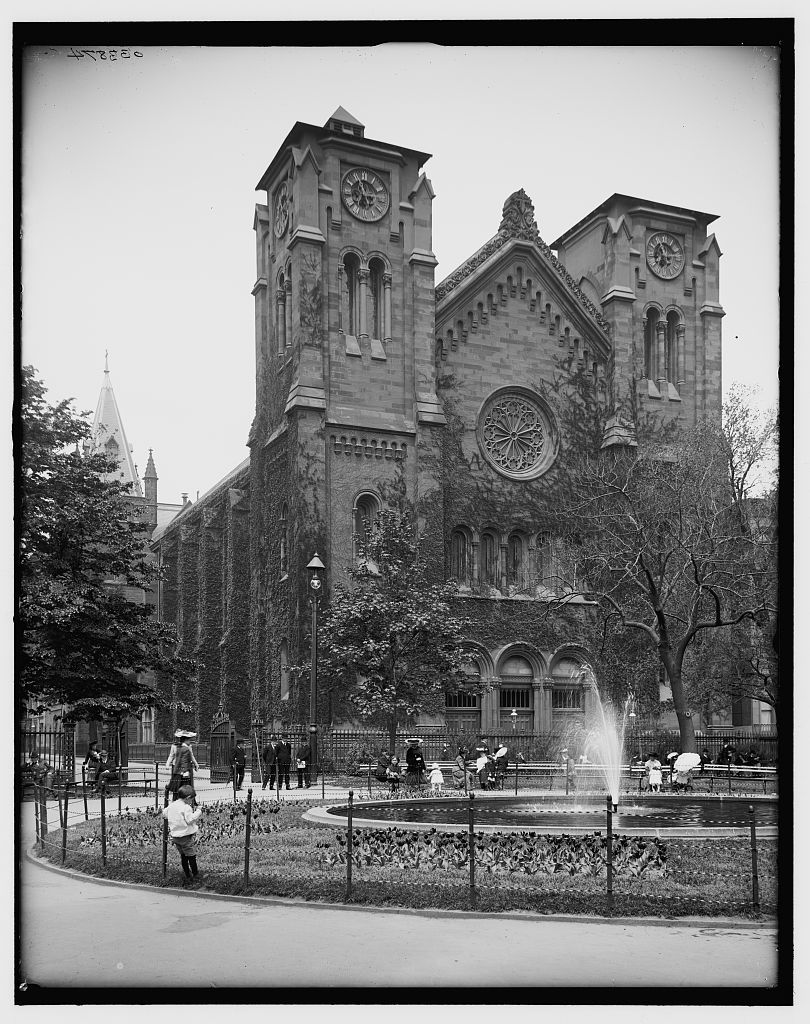

Saint George’s Episcopal Church, at the corner of East Sixteenth Street and Rutherford Place in New York City, burned on November 14, 1865, when fire broke out on the roof. Repairs were underway and a furnace was being carelessly used. Twin spires rising 245 feet above the local park, Stuyvesant Square, were badly weakened in the fire and finally removed in 1889. This is how the brownstone church exists today, near where I live: above matching clock faces, the towers are squared off. Looking up, you feel the absence.

I stopped believing in God around the time my stepfather, Paul, died. But while he was sick, in the years around the turn of the century, I found myself at Catholic Mass every morning, appearing to believe pretty strongly. I don’t remember whether I did believe then, or even what belief felt like in those waning days. Still, when Paul was strong enough, he got a daily ride from the neighbor to his local church in the Midwest, and so, I decided, I’d go, too, in New York. We spoke sometimes on the phone, I recall, but not ever about the morning services we’d both attended—not about the readings from the Bible; not about the sermons, which in a weekday Mass were always brief; not about the gossipy Italian women who gathered in the front pews at St. Mary’s by the Sea, while I tended to sit in the middle or near the back.

It’s been a decade since I stopped attending church. If I’m honest, during the early days of the relationship with the woman I’d marry—let’s call her Kate—we had better things to fill our weekends with: we ate bagels on Sunday mornings, we caught up on The Wire and rented the Bourne movies, we had sex, we took my new dog for walks. In the summer we packed towels and biked through Brooklyn, where I then lived, to the beach at Jacob Riis Park, where we spent the day in the water, on the sand, before biking home, before work the next day. One week I was going to church. The next week I wasn’t.

Still, those weekday mornings in church are my last strong memories of what may have reflected a belief in God. Even in the last weeks of his life, in the late spring 2002, when the priest or the deacon came to the house and delivered Communion to Paul, when I’d returned home and the family prayed together, hand-in-hand in a circle around the hospice bed in the family room, and when the light and the breeze came in through the top of our Dutch door, I didn’t believe. I received Communion brought to the house by the religious visitors, but on Sunday mornings, while the rest of the family left for church, I remained home with Paul, who was too sick then to go. I eulogized him at the funeral in his church—Paul was a good Christian man, among the most generous I’ve known—although by that point I’d abandoned the confidence good Christians are believed to hold in our hearts, that our prayers, especially those spoken for the dead, have an audience: “Eternal rest, grant unto him, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him. May he rest in peace. Amen.”

One Sunday morning a few years ago, though, while walking the dog after stealing a few moments reading on a bench in Stuyvesant Square, I felt the familiar sound of an organ sweep toward me. I have no idea of the tune, but the emotion was the simple attraction that accompanies recognition, a sudden memory, in a phrase I love from David Foster Wallace, “like a thought that’s also a feeling.” The doors had opened and the congregants were descending the stairs of St. George’s. Their music spilled out too and I moved toward the church. “Come,” I said to the dog.

The weather was comfortable; we were in no rush. It may have been Pentecost, the spring holiday ending the Easter season that celebrates the descent of the Holy Spirit, appearing in tongues of fire onto Jesus’ disciples, when they speak in languages they don’t know and Peter converts thousands. I remember the flap of red banners, often flown on Pentecost to recall the descent of the Spirit in tiny flames, the earliest moment of the Christian church.

I advanced only so far toward St. George’s, just past the square’s central fountain, before changing course. The dog sniffed. I wandered down the park’s inner ring of hexagonal paving stones. An observer would not have found any of this strange. People with dogs often shift course to try another tree. Still, I did move at the sound of the music. You might say I was moved.

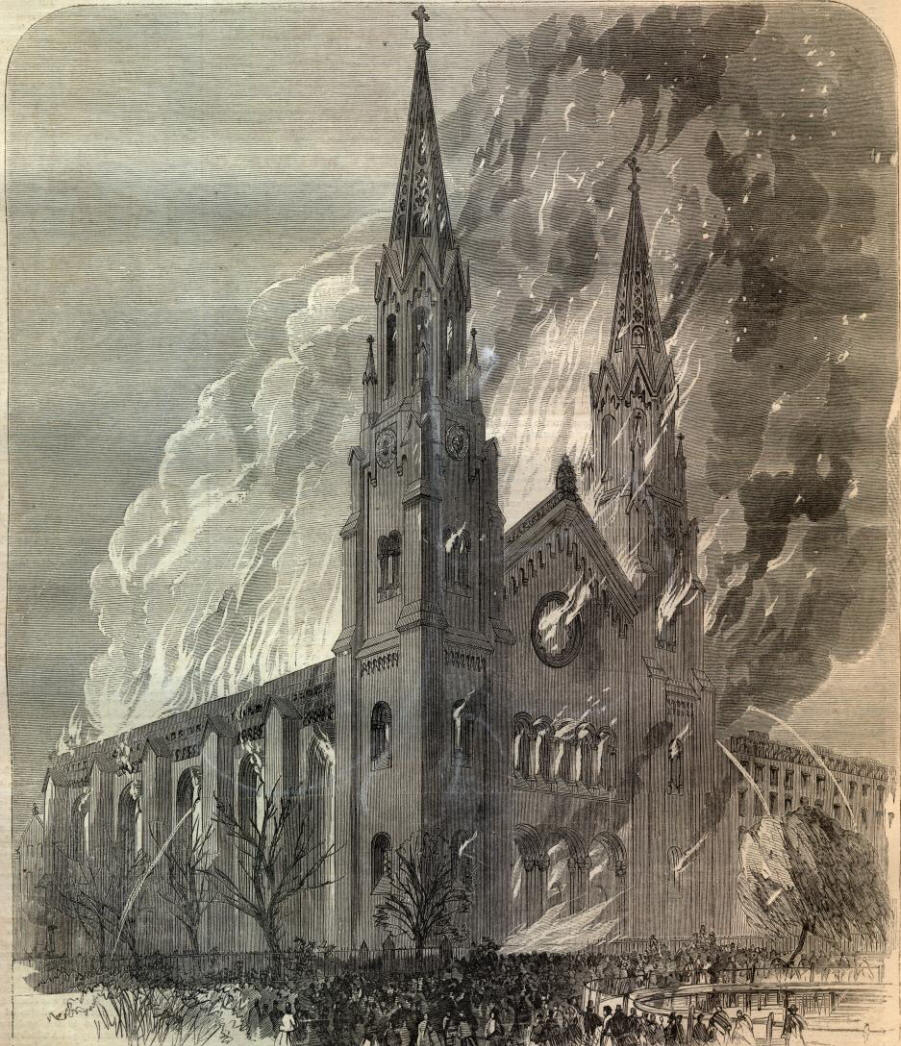

The December 2, 1865, cover of Harper’s Weekly, sketched by Alfred Waud, shows an autumn crowd pressing up against Stuyvesant Square’s iron fence—Manhattan’s second oldest—while a lone figure in a bowler hoists himself above its lip. The attraction is unmistakable. To the west, across Rutherford Place, ribbons of fire ascend through St. George’s windows and a flash of white bursts from the vestibule. Embers rise with the smoke. Firefighters do their best, sending thin streams of water into the blaze, but it is no use. A photograph of the church taken not long after the fire offers a view through two narrow stone windows at the back of the building to the sky above.

Constructed between 1846 and 1856, Saint George’s was home to the congregation of Reverend Stephen Higginson Tyng, who’d commissioned the building of the church. Over two decades, both St. George’s and the park, first plotted out from the Stuyvesant family farm in 1836 and then surrounded by its adamant fence in 1847, had helped draw families to the neighborhood. By the time of the fire, the congregation, it was said, was “more than wealthy enough to rebuild the church.”

Witness to the fire, Tyng was described in Harper’s as “much affected by the spectacle,” though weeks later, preaching a Thanksgiving sermon in the Episcopal Church of the Holy Trinity, he seemed to have put the conflagration behind him. The nation was a new place in late 1865. Tyng, whose son had served as chaplain in the U.S. Army’s 12th Regiment, knew as well as anyone: “We have mercies to record and blessings to celebrate, and deliverances to commemorate today which can never be reproduced.”

During this Thanksgiving sermon, after first welcoming home and honoring men whom these churchgoers had both prayed for and mourned, the reverend turned his attention to slavery:

That barbarous system which compelled the union of ignorance with labor in the South, and by political bravado and bribery exorcised the manliness of multitudes of apologists in the Northern States, has at last been betrayed into its own ruin. When it inspired the late rebellion, it blindly began its own destruction. It is dead by its own hand—a suicide. And for this, in the house of Him who is no respecter of persons, in whom bond and free are one, I do rejoice; yea, and I will rejoice.

Tyng’s phrase “ignorance and labor” to described enslaved black people in this sermon seems to reflect his time and understanding—his own whiteness and his own ignorance; indeed, preaching against slavery earlier during the war, Tyng referred to these same people as a “helpless, unoffending race.” Even so, about their humanity and their persecution, to say nothing of their central place in the country and its history, Tyng was clear: “Their sufferings hung around the nation’s neck, a weight intolerable; their sorrows and their blood unavenged cried out against their oppressors.” Their freedom was the cause of his rejoicing.

The first I ever heard of Tyng was in the course of researching a collection of papers of the writer Harriet Jacobs, before I lived in the shadow of Tyng’s church, before I knew of the fire, before I had the dog. Jacobs was the author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, a book that made her famous in abolitionist circles, even if her name was not on the cover—a narrative of her life in slavery, her seven years in hiding, eventual flight from North Carolina, and her freedom, purchased for $300. She had traveled south to Alexandria, Virginia, from New York, to work in refugee camps. (Of her adopted home, Jacobs had this to say in Incidents, after learning her freedom had been bought: “The bill of sale is on record, and future generations will learn from it that women were articles of traffic in New York, late in the nineteenth century of the Christian religion.”) The letter among Jacobs’s papers that introduced me to Tyng was written by a Quaker volunteer named Julia Wilbur, who, on January 16, 1863, recorded her transport, by ambulance, of a donation of 40 pillows, 17 tin cups, and 22 bedquilts, a gift of the National Freedmen’s Association. Tyng was the organization’s first president, and he gets credit in Wilbur’s letter for his group’s generosity on behalf of black refugees.

A major event in my work on Jacobs occurred the day I discovered her on the rolls of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., a congregation organized by the great African-American minister and abolitionist Alexander Crummell. (Crummell would preside at Jacobs’s funeral in 1897.) I studied Christianity at a graduate school then unofficially presided over by Black Liberation theologian James Cone, and made famous by the mid-century Christian realist Reinhold Niebuhr, who penned the Serenity Prayer, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German Lutheran minister who, after mere months in the U.S. in 1939, returned to Germany to rejoin the resistance to Nazism.

Over the years, and regardless of my unbelief, I’ve identified with these sorts of Christians, the ones people on the political left tend to admire regardless of their own beliefs. Add to Jacobs and Bonhoeffer and Niebuhr the anti-war activists Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and Daniel Berrigan, and the writers Flannery O’Connor and Marilynne Robinson. Martin Luther King Jr. Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama, though not Nixon the Quaker or George W.

The way I’ve come to identify with certain Christians and not others has not always been perfect nor particularly well thought out. But if it’s war I hate, then I should probably hate Niebuhr, who viewed war as occasionally necessary and just, if also a moral hazard; Obama, for his part, was at war even longer than his predecessor. If I need my Christians to defend abortion rights, then I lose at least Berrigan, Day, and Merton, my stepfather Paul, too. Does Stephen H. Tyng’s abolitionism crumble just a little—maybe a lot—under the weight of his racial condescension? We Christians are complicated. Some of us don’t go to church or believe in God or really feel that okay most of the time even calling ourselves Christian.

In 2002, when my stepfather died, the news in Milwaukee was of hundreds of thousands in hush money, paid to a man by the Catholic archbishop; they’d had an affair. The archbishop, whom I’d admired, would step down and virtually disappear. The great international story then, a backdrop to the local one, was the systematic sexual abuse of children and its cover-up going back decades and probably centuries. Around the time I began this essay, the newspaper I usually read detailed mass graves of hundreds of Catholic Irish children born out of wedlock and laid to rest by nuns, over thirty-six years, in a decommissioned septic tank. It’s debatable whether religion itself has done more good than harm.

I’ve grown tired at finding myself in this debate in classrooms and at dinners—tired of the problem and tired of my answers: But King, Bonhoeffer, Day, I say. (Looking ahead I may add Stephen H. Tyng to my list.) But those priests, I hear. The patriarchy, they say—the gays, the Crusades. Yes, I know. But Jesus, I say, though I know, as well, but do not say, Jesus was dead (and raised) by Pentecost. He had nothing to do with the church.

This is an argument I know well from my studies and my days in the church, that although he preached to thousands during his ministry, healed more than two dozen, even raised a few people from the dead, it’s said (this is all said), the number he organized around himself amounted to twelve. He preached a radical ethic against money and for eating together; he healed lepers by inviting them in and not casting them out; his sayings about loving our enemies and hating our families, about the blessedness of the poor and meek, the merciful and mournful, still perplex me. Just as confounding is the possibility that this message, and a life lived by these principles, could have brought people together—thousands in a day—even after Jesus had died. Yes, the greater miracle even than the disciples’ glossolalia at Pentecost was to take the impossible demands of a dead rabbi—“go and sell all your possessions and give the money to the poor”—and build a church from them.

Drawn into the religion by his beautiful and mystical godmother, Jacqueline, in the early 1990s, the French writer Emmanuel Carrère converted to Catholicism and, as he describes in his book The Kingdom, immersed himself completely in the faith, writing long, verse-by-verse commentaries on the Gospel of John, attending daily Mass, finding joy—until it left him. One day—a day he can’t remember—he tucked his Christian writings away in a closet, he says, and eventually forgot where they’d gone. Digging them up while writing The Kingdom, Carrère finds himself embarrassed by his former self: “It has a false ring to it,” he writes of an enthusing letter he wrote Jacqueline in the hottest moments of his conversion: “That doesn’t mean I was insincere when I wrote it—of course I was sincere—but I can’t help believing that someone deep inside me thought what I think now: that all of this is only autosuggestion according to the Coué method, Catholic double-talk….” Still, as it reanimates the light and heat of the early church through a strange novelization of the lives of Paul and Luke, Peter and others, Carrère’s The Kingdom says one thing: Looking up, you feel the absence.

The earliest Christians were nothing like the ones I knew in my church growing up. We were a comfortable and conservative lot, rural Midwesterners who had not been convinced to sell what we owned or to give all that much to the poor. My stepfather, Paul, who was in retail, did more than most in this regard, often working on the weekends as the general manager of a chain of Catholic thrift stores. When Paul died, we mourned together, but it’s hard to say we felt particularly blessed by this. Writing about the revolutionary movement of the earliest Christians and their attractiveness, Carrére offers this explanation:

People are constituted in such a way that the best of them want good for their friends, while all of them want evil for their enemies. They prefer to be strong rather than weak, rich rather than poor, big rather than small, dominant rather than dominated. That’s the way it is, that’s normal, no one ever said it was bad. Greek wisdom doesn’t say it, nor does Jewish piety. Now, however, men are not only saying the exact opposite, they’re also doing it. At first they’re not understood, no one sees the interest of this extravagant inversion of values. And then people start to understand. They start to see the interest, that is to say, the joy, the power, the intensity of life, that the Christians draw from this apparently aberrant behavior. And they have only one desire, to do as they do.

No one I knew growing up had these desires. That’s the way that it was, normal. It’s what I learned. And so, it’s hard to say how, in practical ways, I’ve sought out poverty, say, as Dorothy Day did, living in communion with the poor in New York City’s East Village, near where I live, or on a Catholic Worker farm in Eastern Pennsylvania; or as Harriet Jacobs did, living among black refugees in Alexandria, Virginia, opening a free school for children, collecting, sorting, and distributing goods donated by Reverend Tyng’s association of abolitionists. I’ve got far more in common with that onlooker in the bowler hat, I suspect, watching his church burn from behind an iron fence, knowing everything will be fine, than I do with any of those heroes I claim to identify with when I’m told we Christians have done more harm than good. Carrère, too, ends The Kingdom, he says, “encumbered with everything that makes me what I am: intelligent, rich, a man at the top—so many obstacles to entering the kingdom.” And while I believe I face with Carrère these same obstacles, admitting them also implies the ongoing attraction of Christianity—which ultimately also explains my defensiveness, a thought that is also a feeling. I’m attracted to a joy I once must have known in community, where talk of the soul introduced me to the central mystery, and reality, of human dignity; I’m attracted to the comfort my belief in God provided in my mourning, my fear, and in the mourning and fears of those I loved; I’m attracted to the hope and ambition that have long burned in me to live in the model of Christ, to one day be deserving of the church he inspired, even as it’s failed and failed and failed—as I have, and as I will always—to live up to that “extravagant inversion of values” he preached and his earliest followers are said to have lived so intensely.

I’m not going back to church. And yet, though the dog has died, I know that some days I’ll wander through Stuyvesant Square, and it may come at just the right moment: I’ll be moved—physically and in my mind, my soul—at the sound of an organ and at the sight of the crowds under the clock towers. It’s happened before. And I know, too, that certain thoughts will occasionally still arrive, usually in the dark, either at the end of a hard day or in advance of a harder one: Dear God, I’ll hear myself think. And maybe there’s the second thought, which usually begins with please. Please. And while I say there’s no God listening who might care about these thoughts, whatever they might be, there used to be. I know that.