I FLEW TO Turkmenistan for the first and only time in 2018, a few weeks after a video surfaced showing the country’s president, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, lifting an empty golden barbell in honor of the Weightlifting World Championships to be held that year in the capital city of Ashgabat.

In the video Berdimuhamedov, a sturdy, graying man in shirtsleeves and a black necktie, appears behind a weightlifting platform, flanked by traditional flags; cut to his cabinet ministers, who are already applauding. He strides to the empty bar and hoists it to his chest, fumbling slightly before lifting it over his head to continuing applause, his smile both wide and expressionless. In his grasp the bar teeters perilously to the left.

Autocrats often cultivate an athletic image to vaunt their power. In the present instance the golden bar adds an extra veneer of dictatorial ridiculousness to the proceedings. Empty, made of gold, Berdimuhamedov’s barbell is the perfect avatar for the hollowness of masculine posturing: a luxurious falsehood. But the members of his cabinet remain on their feet for the entire video, applauding rhythmically, like automata.

By 2018, Berdimuhamedov had been the dictator of this Central Asian country of 6.4 million for 12 years. Turkmenistan, a Soviet Republic from 1924 until 1991, hadn’t hosted many international events, and the Weightlifting World Championships represented a significant occasion. I attended with my father, a sports scientist and author, with whom I’ve traveled to dozens of weightlifting competitions. This would be my third in a post-Soviet Central Asian country, having visited Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan for previous events like this one.

My father’s weightlifting career spanned the ’70s and ’80s; he once trained and traveled in Russia behind the Iron Curtain, so he’s able to recognize certain customs as holdovers from Communist times. Turkmenistan’s barren capital city offered many such opportunities.

Ashgabat seems to be entirely composed of marble and gold, and it also appears to have been all but abandoned, despite being home to a substantial part of the country’s population, perhaps as many as half; published population figures are almost certainly false, according to multiple sources. Radio Free Europe reports that millions have left the country due to a lack of opportunities and personal freedom. Berdimuhamedov has withheld census data, according to the CIA Factbook.

Even before the pandemic, foreign visitors to Turkmenistan were tightly restricted though onerous visa requirements; the country received just a few thousand visitors per year. (Its Tourism Committee website was recently disabled altogether, though the Wayback Machine has an archived version.)

Walking around Ashgabat felt to me like visiting Disneyland after the rapture. There’s no litter on the sidewalks and no billboards on the highways, only manicured shrubbery and silence. Aside from a handful of soldiers and a single person taking the bus, the streets stayed empty for my ten-day stay save for groups of uniformed women with straw brooms, scraping away at nonexistent refuse. The city gleamed in the sunlight and lit up at night in shifting candy-colored hues set off gorgeously against the white marble. For years it was illegal, in Ashgabat, to drive a vehicle in any color other than white.

Even in this barren landscape, I felt watched wherever I went. Public bathrooms often had attendants who seemed more interested in keeping an eye on the stalls than in making sure they were supplied with toilet paper. Having once illegally exchanged currency in a Central Asian bathroom, I found the extra security unnerving. Elevators were guarded in our hotel, and soldiers lined the streets. Before entering the hotel compound by car, my father and I had to submit to TSA-like body scans, and our bags were searched by armed security officers. We wore our passes around our necks at all times, and were expected to scan into every location we entered so that data could be logged. Each of us was assigned a guide—a boy for my father, a young woman for me—who stuck by our sides every hour of the day.

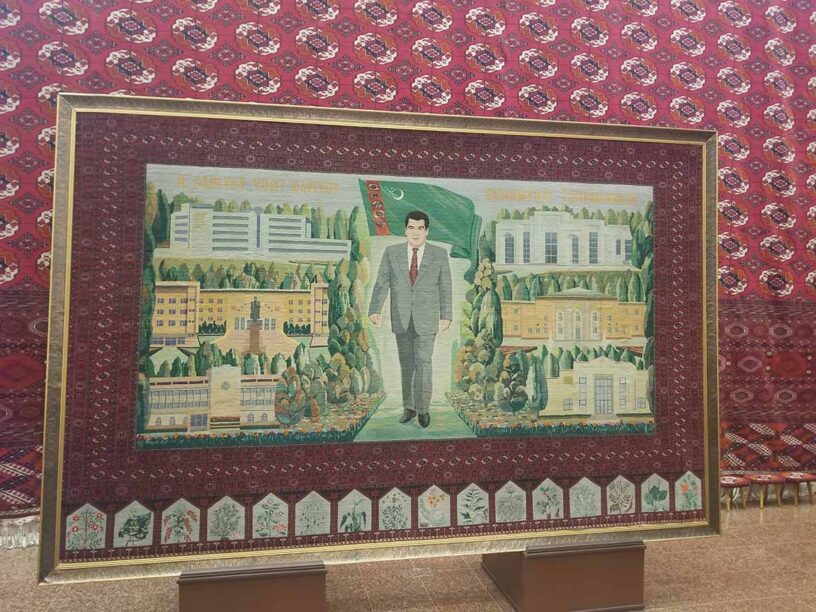

I have fewer photos from Turkmenistan than other countries I’ve visited for weightlifting events. Using my phone in public felt reckless, or suspicious. Most of the photos I have were taken inside the museum, where the lifters, coaches, and members of the media were taken for guided tours. We were filmed the entire time by a Turkmen camera crew, but were never told why. One subject I couldn’t help capturing, over and over, was Berdimuhamedov. He was everywhere—embroidered in hand-woven rugs, in portrait after portrait hanging on the walls. In the center of the museum there’s an immense image of the president, much larger than life size, in which he is walking on an emerald green carpet and waving. Birds soar behind him above pristine marble landmarks. There are rainbows. Below the portrait rests a scimitar in a jeweled hilt kept in a class case.

Berdimuhamedov won Turkmenistan’s first presidential election with multiple candidates in February 2007, after his predecessor, Saparmyrat Nyýazow—official title President for Life—died in 2006. Berdimuhamedov has had extraordinary luck in subsequent elections, winning again in 2012 and in 2017 with over 97 percent of the vote. He stepped down in February 2022 as head of state to become head of the Halk Maslahaty, or People’s Council, one of the main governing bodies in Turkmenistan. Another presidential election was held; his son emerged victorious, after capturing what must have been a disappointing 73 percent of the vote.

For as long as men have ruled empires they’ve tried to prove, or pretend, that their bodies are superior to those they’ve conquered, and the distance between the macho fantasies and the lived reality is often grimly comical. Italo Calvino’s essay on the evolution of Benito Mussolini’s portraits and Janet Flanner’s pre-Holocaust feature on Adolf Hitler appeared, decades apart, in the New Yorker, both excellent catalogs of flexing dictators: Mussolini disguising his bald head with a manly helmet, and Hitler camouflaging his perpetually dyspeptic, weak, malnourished body with military trappings and tough-guy posturing. Vladimir Putin loved posing shirtless on a horse, and Donald Trump’s hair weaves and globs of orange makeup grow increasingly wild. Can there be a correlation between these absurd displays and the dictatorial goal of limiting personal freedoms and public resources for millions of people?

Other, even sillier, videos of my dictator have emerged in the past decade: Berdimuhamedov shooting targets with a handgun from the seat of a bicycle; Berdimuhamedov in military fatigues flinging knives at targets, recording a rap video with his grandson about the importance of sports, unveiling a giant gold statue of a Central Asian shepherd dog modeled after his favorite pet. This last one appeared in November 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged around the world, claiming millions of lives. Turkmenistan is among just 11 countries to report zero COVID-19 infections or deaths to the World Health Organization, and it is, tellingly, the only non-island nation on that list.

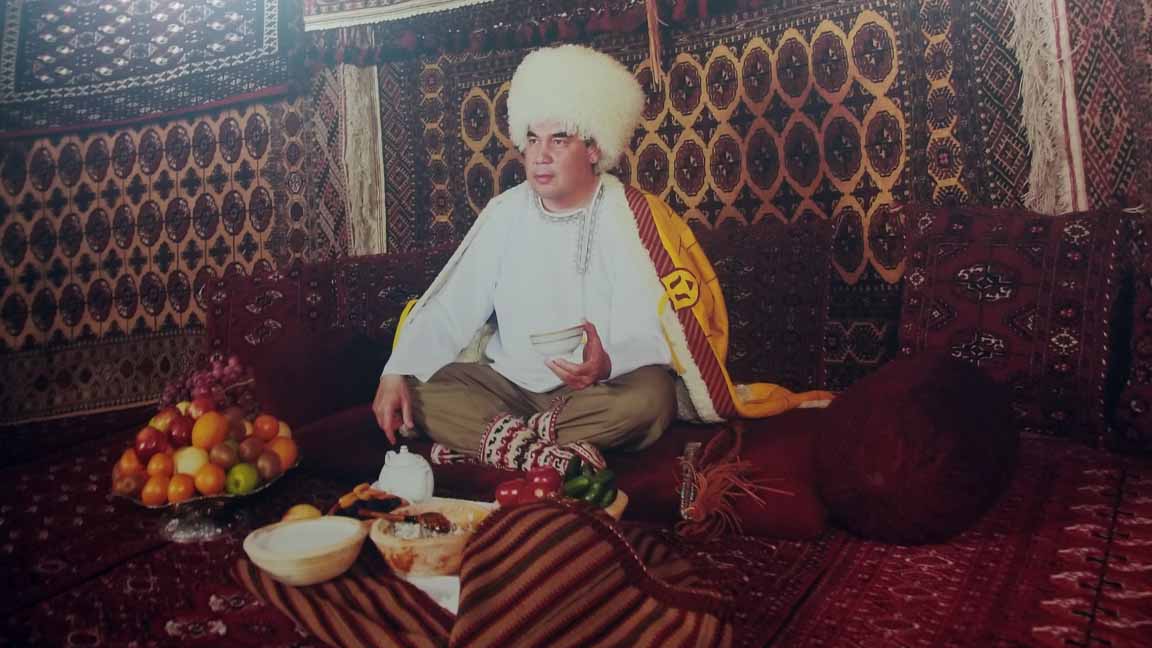

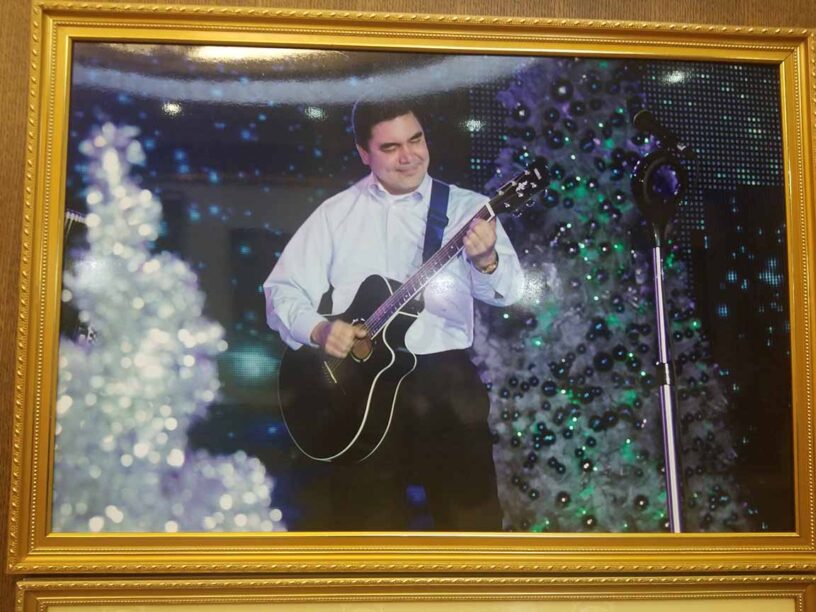

When I visited the museum in 2018, I wandered into a circular room where photographs of Berdimuhamedov surround you on all sides: there he was, playing guitar on a stage surrounded by Christmas trees, then sitting on a carpet in a white fur fez deep in thought; a serious image of his face that looked eerily like a cartoon, gazing serenely into the middle distance. As I marveled at these portraits of the president, who appears to deeply love his country but perhaps not the people in it, I wondered why my grandmother had so rarely discussed Mussolini. She was born in 1924, and so must often have seen the ubiquitous portraits Calvino described. Her comments on il Duce, however, were mostly restricted to his weakness as a leader and the fact that it was he who had commissioned the construction of the homes in her neighborhood that had crumbled under Nazi occupation. It was in this decimated village that she met my grandfather, a Polish soldier and raging alcoholic, whom she married and eventually fled with to Canada. Most of the circumstances that carried my grandmother to America were brought about by the failures of weak and violent men in power, men who wished to be strong, and who fantasized that they could be the architects of a better world. Through their vainglorious arrogance, we can be certain that their images will never be forgotten.

Thank you for visiting POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!