In my early twenties, I worked at a women’s magazine, covering culture and entertainment. I loved my job: attending movie premieres and museum openings for work, interviewing celebrities, and creating fun quizzes, like “Which Avenger would make your best brunch buddy?” I was young and naive enough to believe that politics would never crawl into my cheerful, glitter-covered world of glossy pages.

This illusion was shattered in 2014, when I filed a story about the actor Neil Patrick Harris, and my editor told me concernedly: “You need to run this through the legal department.”

Russia had recently annexed the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea, a frightening moment Putin called “the return.” (Millions of Russians, myself included, called it “WTF?!”) So began the subtle, yet constant fear of horrific changes to come, not only in our country’s foreign policy but at home, too.

The previous year, Putin had signed the first anti-LGBTQ law in Russia’s modern history, banning “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations among minors.” Protests were held, but they weren’t massive. The restrictions seemed absurd, and therefore, not significant enough to warrant outrage. But the law represented real repression.

The paragraph that had so disturbed my editor read: “A womanizer on the screen, in real life Neil Patrick Harris is happily married to actor David Burtka. The couple raises two children.”

The lawyers were quick to respond. They strongly advised me to lose the word “happily,” since this could be regarded as creating an attractive image of same-sex relationships, a.k.a. “propaganda.” They also recommended not mentioning that the couple was married, writing instead that the two men were “involved.” According to the new legislation, they explained, homosexual relationships could not be equated with “traditional” ones, including marriage; the same went for raising children.

This experience of censorship left me bitter, as many things that year did.

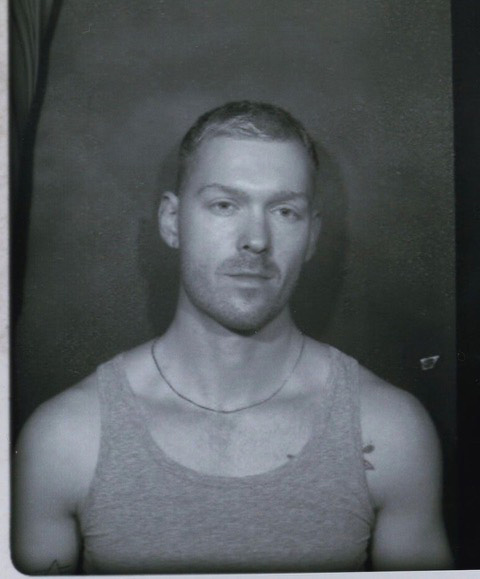

I asked my friend, New York-based fashion photographer Arseny Jabiev, what the LGBTQ community’s reaction to the new law had been back then, when he was living openly as a gay man in Moscow.

“There was none,” he said, adding that he was referring solely to the response from his own, privileged community of Moscovian creatives—people who worked in fashion, media, and entertainment. “We loved our comfort, money, and social positions. Most didn’t want to jeopardize it all.” But even privileged LGBTQ people in Russia were deeply traumatized, he told me. “We aimed for safety and a somewhat normal life, not fights.”

Jabiev responded to these events by creating art, including a photograph that created a big buzz in post-Soviet space: two young women kissing passionately, with flags painted on their lips—the Russian and the Ukrainian ones.

Eventually Jabiev could not stand the growing lack of freedom, both personal and artistic, and he left Moscow for New York around 2017. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, his became one of the loudest voices of protest in the fashion industry.

Around the same time Jabiev left Russia, I made a move of my own—professionally, not geographically—to cover social issues and the civic sector.

Violations of rights of all kinds, especially the rights of the LGBTQ community, emerged from my reporting on the work of nonprofits and civic organizations. The government began blackmarking LBGTQ organizations with a “foreign agent” label designed to create difficulties in the work and lives of people and institutions. I protested, alongside my friends and colleagues, against the new Constitution of 2020. Among other things, it allowed a ‘reset’ of Putin’s previous presidential terms, and established that only the union of a man and a woman can be considered marriage in Russia.

In 2022, the same year Putin started a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he signed a new, expanded version of the anti-LGBTQ law, outlawing any public displays of LGBTQ behavior in Russia. The legislation’s vague content sent chills and confusion across the country, and there was worse to come.

A wave of weird initiatives swept across regions and industries. A city mayor banned an art project featuring colorful statues of pigeons, meant to have been displayed in the city center (“But there were eight pigeons, and the colors didn’t even match the rainbow!” the bewildered artist responded). A renowned theater festival struck the word “Rainbow” from its name. Streaming platforms cut scenes from television shows like Sex and the City and The White Lotus (surely rendering the latter series all but incomprehensible; what can be left of the story if you cut the word “gay” from it?!)

These preposterous scenarios should exist only in science fiction, not in the real life of a modern country. But the absurdity conceals the real oppression experienced by Russia’s embattled LGBTQ activists. Outlawed, some are forced into hiding; others come out, and lose their careers and homes.

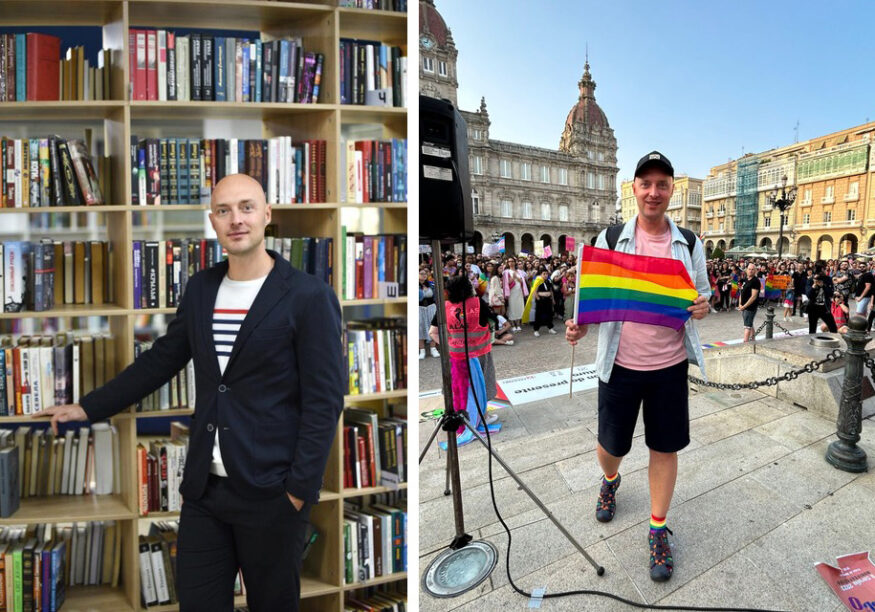

At the end of 2022, a list of books to be banned from libraries was leaked to the press. The titles included novels by Stephen Fry, Hanya Yanagihara, Haruki Murakami, Michael Cunningham, Virginia Woolf, and Truman Capote. The source of the leak was identified as Vladimir Kosarevskiy, the former head of Moscow’s Anna Akhmatova Library.

In an interview for Novaya Gazeta (a publication blocked in Russia after its editor received the Nobel Peace Prize), Kosarevskiy confirmed the reports and publicly came out as a gay person; already, before the new legislation, he had had to face bullying, humiliation, insults, and violence. He knew “how silence could multiply crimes.”

Kosarevskiy was fired from the library. He realized that his beliefs, morals, and actions were, as he put it, “incompatible with a comfortable life in Russia,” and decided to emigrate. He told me that Russians have thanked him for standing up for the truth and saying out loud the words most people are afraid to say.

We’ve protested, we’ve fought. How have we come to this? How far do we stand from the last circle of the Kremlin’s version of this human rights hell?

Perhaps not very far at all. In June 2023, Putin ordered the creation of an institution to research the “social behavior” of LGBTQ people. Many activists interpreted this move as proof that Russian authorities plan to begin conducting “conversion therapy,” a set of traumatizing practices intended to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. The Duma has also passed a bill to ban legal gender changes and gender-affirming healthcare entirely.

Vladimir Kosarevskiy is building a new life in a new country; along with millions of Russians, he still hopes for Russia to break free from Putin’s regime. But he also remains deeply worried by what is yet to come: “How quickly we have come down to all this… And how much further can we sink, if we continue on this path?”

Last year, I left Russia too. In visa-language, I explained that I wanted “to explore career opportunities abroad.” Among the opportunities that opened up for me—as for other fellow journalists who’ve left Russia since February 2022—was the ability to write freely and openly about the war, and about the growing social injustice in our homeland. This piece, for example, violates both the anti-LGBTQ law and some of the infamous war censorship laws that carry penalties of up to 15 years in prison in Russia.

Russia is not alone in its spiraling towards the Middle Ages without rights and freedoms. Though it had long seemed that the world was moving towards acceptance of LGBTQ people, many other countries have been tightening anti-LGBTQ laws, including the UAE, Uganda, Nigeria, and Iran, all joining Russia at the bottom of the LGBT Equality Index ranking.

Now, as I “explore career opportunities” in the areas at the top of the list, I look around and can’t help but envy people who grew up in democratic societies. I am amazed by people’s awareness of their rights, their protest potential, and the absolute conviction that power must rotate. Can such a society somehow slide into full-scale censorship, a ban on fundamental freedoms, and legalized tortures? Or are the ideas of human rights rooted so deeply in such societies that they can only be shaken, not torn out?

Ultimately, these thoughts guide me to hope: if democracy, having once emerged as a response to oppression, could take root in one place, surely it can develop in another. We just need to not give up.