Behold the vampire coal barons, who suck the marrow from the earth! Behold the sirens gorged on profit, their voices filled with credential, leading us into danger and sickness! Behold the Jekylls and Hydes, plunderers who transform into reputable gentlemen for the statehouse!

Behold: these are the monsters of West Virginia.

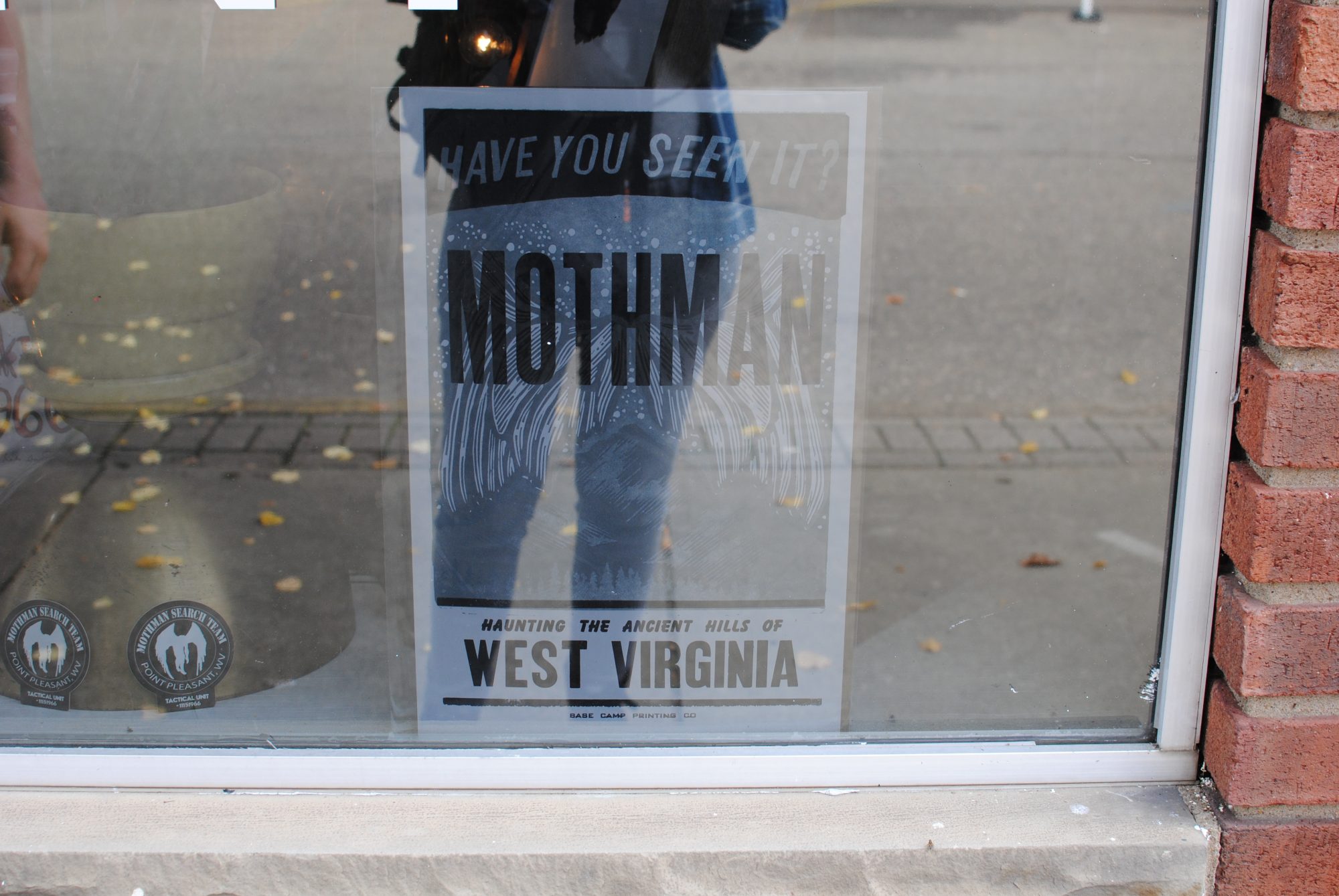

I come to you with a petition to exempt one from their number, the Mothman of Point Pleasant.

Mothman is not a monster; he is one of us. A man from New York carried off his story and sold it. Wealth was made in his name. When hard times compelled his migration, new cities received him, but only as a sinister interloper. And so, he carries the future of places and people that deserve better on his wings.

He is a hardy survivor; he is misunderstood; he is at home among the discarded and painful remnants of our industries. He is a witness-bearer and a clumsy oracle.

Let us be in fellowship.

In West Virginia, things cannot be undone. Twenty years after the government stopped producing munitions at a secluded factory near Point Pleasant, the land still teemed with contamination. And so it was that in 1966, five men digging a grave reported seeing a winged figure flying overhead, looking down with eyes glowing redder than red. Other sightings soon followed: Thrill-seeking couples cut through moonlight in their overheated cars, tracking, eager for a brush with the supernatural. Pursuit followed to the toxic borderland, a fitting home for a mysterious creature.

Land rendered long barren had, at last, given us new life.

“It didn’t mean to harm us,” Mrs. Roger Scarberry told the Athens Messenger of her encounter, later the same month. But if not to harm, what did it want? An answer was produced a year later: during rush hour on December 15, 1967, the Silver Bridge connecting West Virginia to Ohio collapsed. Forty-six people died.

Perhaps the Mothman had tried to convey a warning. Perhaps his red eyes were filled not with malice but with grief. This grim duty found purchase with his biographer, John Keel, author of the 1975 book The Mothman Prophecies. The 2002 film adaptation also favored this explanation: “Great tragedy on the River Ohio,” the Mothman predicts.

I think of the Mothman’s first appearance at a graveside, and I extend him the compassion I extend to all made out of place by mourning.

Those of us who find communion with the Mothman see him not as a creature that causes pain, but one that does his small part to take it away. He is the patron of Point Pleasant, and his legend is the anchor of what Alison Stine called “the Mothman economy.” After the release of the film version of The Mothman Prophecies, the annual Mothman festival became a significant source of revenue for Point Pleasant. The festival breaks the loneliness of Appalachia’s inheritance of depopulation and economic stagnation. It is Christmas for a community that spent many years dreading the December anniversary of the bridge collapse.

“Where I’m from, a small town in the middle of nowhere, the gay man was the bogeyman,” wrote John Paul Brammer in an essay about why he celebrates the Mothman as a queer icon. Mothman transforms from monster into a mirror we can hold up to others, and allows us to speak the things that weigh on our hearts: Sometimes, monsters look more like you than us. Subversive imaginations are often humorous ones, and the Mothman liberates us from our complex negotiations of self with joy.

I have my own Mothman story.

When I was homesick—having moved from east Tennessee to Texas—I purchased a box of expensive chocolate ice cream bars and stuck two red candies as eyes on each treat. I ate them with my partner, these homemade Mothsicles, in defiance of the poverty that had ground us down and that had taken us from home. We indulged and schemed of home-going: we promised ourselves that by the same time next year we’d pay a visit to Point Pleasant, a spiritual home if not a literal one. We had few other treats in the year that followed. We made it home, and then my home left me.

My grandfather died just days after our odyssey ended with our two tiny cars parked snugly in the driveway of the childhood home that would never be that home again. We had not returned in time. My guilt, and grief, were enormous. My hometown became alien and uncomfortable in my bereavement. The reunion that I had long hoped for had become a goodbye to the person who always made me know that I belonged. I had no place to put such sadness, and so—when the “same time next year” arrived, because we are people of our word—I took it with me to Point Pleasant.

The Mothman stands on a pedestal in downtown Point Pleasant above the small empire of his creation. The statue’s physique is notorious. Mothman’s sculptor, Bob Roach, exaggerated his human elements more than his supernatural ones. We are a people who want badly to be unbreakable, and this sometimes translates into uneven representations of strength. The rumor has it that Bob designed the statue to have glowing eyes but the town couldn’t carry the expense of electrifying it. (The Mothman, like all of us, is burnt out.)

We paid our visit in September, when vendors filled at least three blocks for the annual festival. There was a noticeable absence, however: Carolin Harris, owner of the Mothman Diner and unofficial town grandmother, had passed away. We bought scratchy T-shirts printed in Carolin’s memory and bowed our heads at the artifacts from her restaurant placed conspicuously in other store windows for display. Around us, face-painted children roamed the streets in search of costumed heroes. Life goes on, because it must.

The line to visit the Mothman wrapped around the block, and by the time I made it to the front I was sunburnt and self-conscious. I didn’t know what I had come there to do, but I knew that a crowd of people anxious for their own audience was not the place to do it. We left and returned the next day early in the morning, when fog from the Ohio River still settled into every nook of the town. We were alone and unnoticed by the vendors breaking down their tables and food trucks.

My heart was full. And not with the sort of hyperactive, indulgent qualities I’m prone to bestow on legends, but with the memories of better days. The time I took a road trip in my early twenties with my best friends, when I climbed the statue and kissed its cheek. The time not long after I met my partner, when I asked to borrow a shirt and received a much-loved Mothman shirt almost identical to one I owned, and just knew that much-loved would be a thing for us. The time I left one of my favorite Mothman souvenirs in a friend’s car and she taunted me with mock-threatening letters about its safety, complete with cut-up letters from a magazine.

The time I stuck red candies on an ice cream bar and announced that we were going home, and we did.

On the outskirts of Point Pleasant, there is a memorial to those who died in the Silver Bridge collapse, and to walk the entire length of the town is to start with an imposing creature of fantasy and end in the fellowship of real people, like Alma Duff and James and Timothy Meadows.

When we left again, I said, “Goodbye.” I also said, “See you next year.”

Elizabeth Catte