At Paga, Ghana’s northernmost border crossing with Burkina Faso, my friend Francis used to own a hot ramen stand. He served one item, Indomie, a type of instant ramen noodles that customers could customize with sautéed vegetables and fried eggs. Every night he would set up shop from 7pm onward along the highway into Burkina Faso; occasionally his wife would join him, assisting with food prep, chatting with customers. As the nights droned on, Francis would cook by flashlight until he was sure his nightly river of customers—immigration officers, tired truckers, and occasional travelers—had stopped flowing.

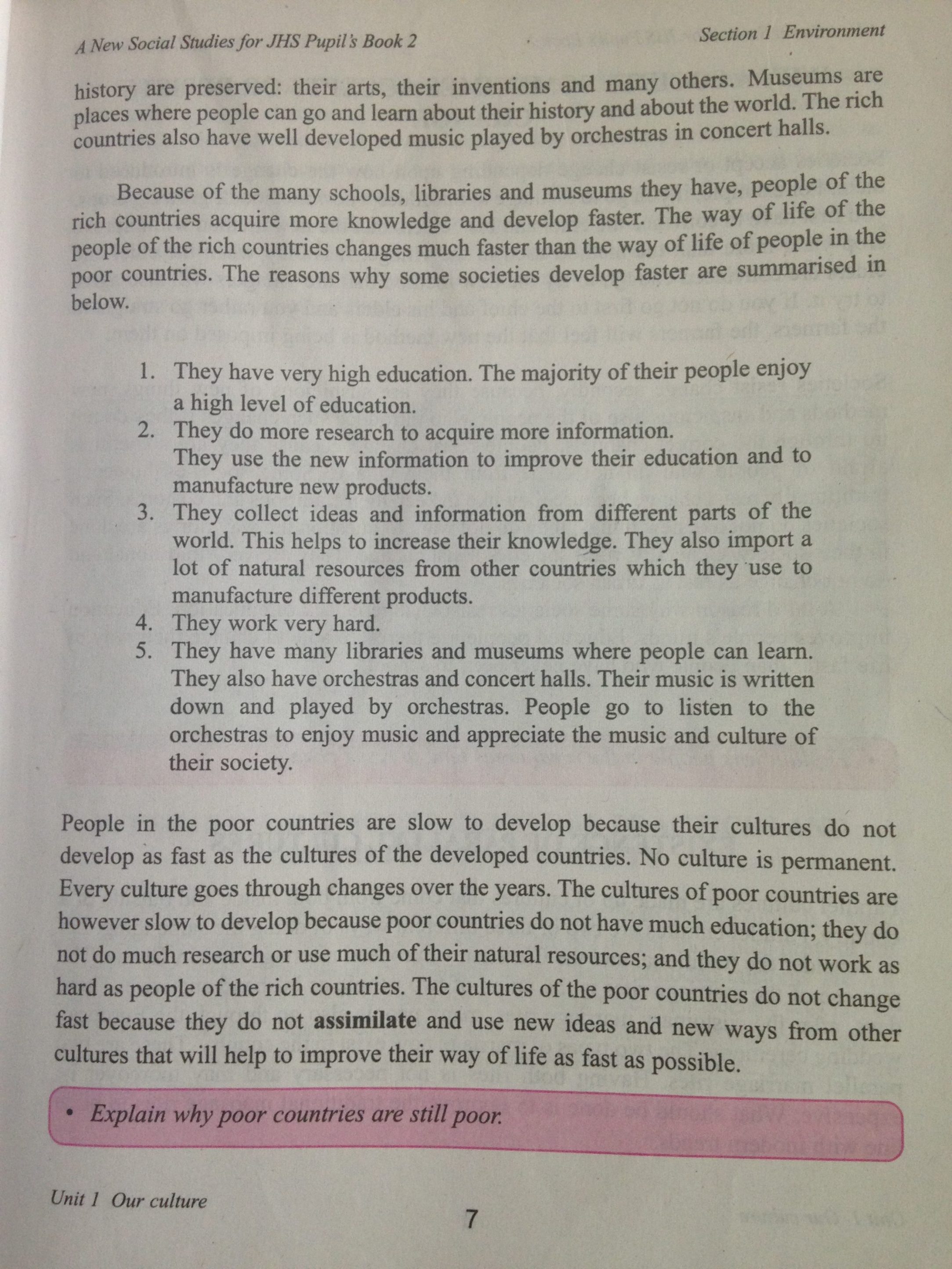

One night as we sat waiting for customers, he told me about textbooks. During the day, it turned out, Francis taught junior high at a nearby private school, Kambridge Academy, where one of the questions his pupils had to answer was to “explain why poor countries are still poor.” According to the social studies textbook Kambridge used, the answer was “culture.” Citizens of “rich” countries “work much harder than people of the poor countries.” Or so they were told by the textbook which Kambridge supplied, and which had been approved by the Ghana Education Service. That textbook taught that countries like Ghana are “poor” because they “do not assimilate and use new ideas and new ways from other cultures that will help to improve their way of life.”

After Francis had completed his primary through tertiary education, he earned his degree from the premier University of Ghana, but he still could barely make ends meet. “Cambridge with a K” (as he called it) charges tuition, but Francis could not earn enough money teaching to cover the costs of rent, transportation, food, and soon, his first child.

And so, after Francis had been teaching all day, he would cook late into the night, sometimes closing shop close to midnight.

***

A nation defines itself for its younger generations in the pages of textbooks like these; social studies is where students learn about their culture and the modern nation-state, where citizens are educated into being. Since Ghana is still a relatively young country, its self-definition is all the more vital, and all the more complicated by its very recent and traumatic history. After centuries of what these textbooks tend to sanitize as human “trade,” followed by colonial rule, Ghana was the first nation to declare its independence from Britain in 1957; Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president, was a staunch pan-Africanist who believed that a strong state and patriotic citizens could lead the country and continent into a new era. And so, as Bayo Holsey has observed, a desire to tell the Ghanaian story as a nationalist triumph can lead to “abjections on the ground” being downplayed and left out of the national narrative (as she notes, “in the context of the story of colonialism and independence, the history of the slave trade cannot find footing.”)

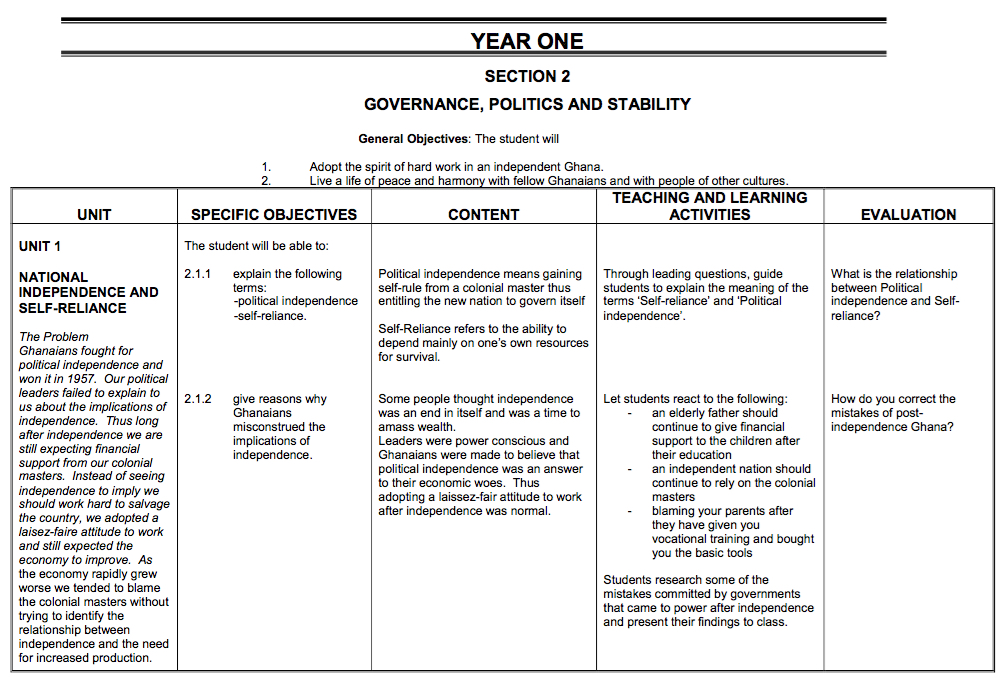

And yet Nkrumah’s vision of state-centered development was short-lived. A series of military coups, beginning in the 1960’s, left behind both political instability and leaders that embraced international development financing and neoliberal reforms. The World Banks structural adjustment programs and the economic “liberalization” demanded by agencies like the Millennium Development Corporation and USAID had the effect of leaving the state a mere partner, rather than a driver, of its own development. Although these policies produced stagnant growth, “development” has remained the focus of both government discourse and social studies curricula. Textbooks like the one Francis used at Kambridge are produced by private publishers but they follow official curricula published by the Ghana Education Service. This state curricula, called a “teaching syllabus,” outlines general objectives, gives suggestions for how to teach and assess student performance, and includes sample classroom activities.

For instance, in the first year social studies unit for senior high students, students are to be presented with the “problem” of “national independence and self-reliance,” and they are to be taught that because “our political leaders failed to explain to us about the implications of independence,” Ghanaians failed to “identify the relationship between independence and the need for increased production” and “adopting a laissez-faire attitude to work after independence was normal.” As a result of these layers of personal and political failures, Ghana was neither “self-reliant” nor “politically independent.”

To teach this lesson, the syllabus suggests a “teaching and learning” activity in which students respond to a series of statements:

- an elderly father should continue to give financial support to the children after their education

- an independent nation should continue to rely on the colonial masters

- blaming your parents after they have given you vocational training and bought you the basic tools

As with Francis’ textbook, the state-sanctioned syllabus suggests that Ghanaians are at fault for their lack of independence, self-reliance, and low production because of their tendency to “rely on the colonial masters” to fulfill their needs. In a particularly jarring characterization, the syllabus likens the “colonial master” with an “elderly father,” calling upon the audience to pity this fictional old man whose dead-beat kids continue to ask him for cash.

In short, the syllabus echoes well-worn apologias for colonial rule by consistently likening colonialism to “education,” “vocational training” and the provision of “basic tools.” To say the least, this is an unsettlingly cheerful depiction of centuries of terror, purposeful under-development, and the active destruction of livelihoods and communities.

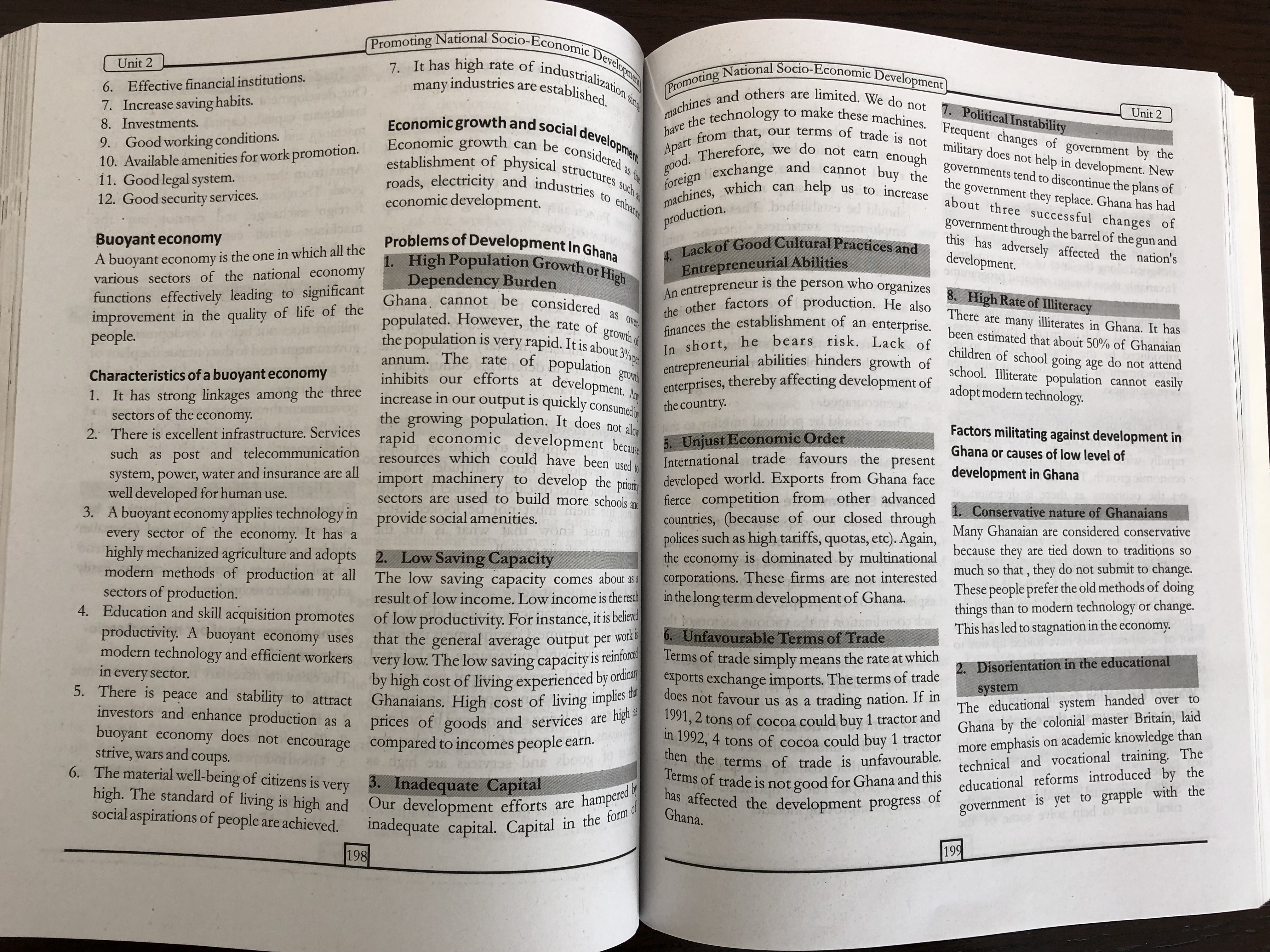

Then again, isn’t this the world that Ghana finds itself in? Africans are constantly under pressure not to use colonialism as an “[excuse] for not going forward,” as Barack Obama told hundreds of young Africans at a leadership fellowship in Washington, in 2014. It’s a charge which has been echoed by Ghana’s current president, Nana Akufo Addo; instead of re-establishing a state-driven development model, his Ghana Beyond Aid campaign seeks to encourage private industry to step in where African leaders have “failed.” He made international headlines when, in a press conference with French President Emmanuel Macron in December of last year, he implored his fellow Ghanaians “to get away from this mindset of dependence.” Ghanaian social studies textbooks teach the same lesson, that development has been stymied by a “dependency mentality,” “laissez-faire attitudes,” and irresponsible parents who don’t send their kids to school.

If Francis’s students learn lessons about individual responsibility, industriousness, and capital-driven development, their textbooks also register some of obstacles that stand in their way; they also explain that poverty can force parents to make tough decisions between sending children to school and having them help in the farm or at home. The books describe how Ghana exists within an “unjust [world] economic order,” with “unfavorable terms of trade,” in which world trade and economic organizations dictate the country’s path. And despite espousing the “benefits” of colonization, the books do note that “Europeans regarded African culture as barbaric and inhuman and African people as inferior human beings,” and that this resulted in a “distortion of culture.”

So what are we to make of these texts that depict Africans as lazy, poor, and underdeveloped, but also reflect the aspirations of a young country yearning for true independence?

These textbooks show the reality of a nation grappling with centuries of trauma and with the pressures of a world system to “modernize,” and thus liberalize the economy; these pressures result in the slave trade being described as a loss of “Human Resources” and farmers being described as “[unwilling] to accept new technologies due to illiteracy and ignorance.” It results in striking contradictions; while wars fought for independence from the British are blamed for the “disintegration of the Ashanti Empire” they are also praised for the “establishment of British authority [who] colonized the Asante.” But if colonization is depicted positively—credited for unifying Ghanaians into a single state, with a national language (English) and identity (Ghanaian)—regarding the collapse of one of the largest African empires as negative reveals a tension that is found throughout these social studies books. The colonizer is celebrated; the colonized are mourned.

Beyond the contradictions, however, one thing is consistent: citizenship is production. From units describing slavery as the theft of “human resources” to the “slow development” blamed on the “indiscipline” of the youth, these social studies textbooks reduce Ghanaians to their productive capacities, valued only for what they can produce for the nation (and, of course, for the private capital that drives the nation).

What lessons might be lost when students are taught that humans are labor units rather than describing the political, economic and racial histories behind such designations? What lessons might be lost when colonialism is described as the kind of cultural transformation that an independent government should emulate, rather than explored through its economic logic and terrifying violence?

What lessons could Francis teach with such a textbook?

***

Francis no longer teaches. With the birth of his first son, his low wages and long hours meant too much time away from his young family with little to show for it. Today, he manages an organic farm outside of Accra.

When he reflects on his time in the classroom, Francis explained how the tension between seeing students as economic units of productivity and seeing them as learning human beings would play out. “I had a disagreement with the owner of the school once because I brought the kids out one night so I could actually show them how the moon orbited the earth,” Francis remembered; “He was furious! He was like I had to have them inside the classroom telling them about possible exam questions.” Francis continued, “I was not teaching kids to pass some damn exam. I was teaching kids who would run a country one day. I taught them to be serious leaders, not processed goods off some production line!”

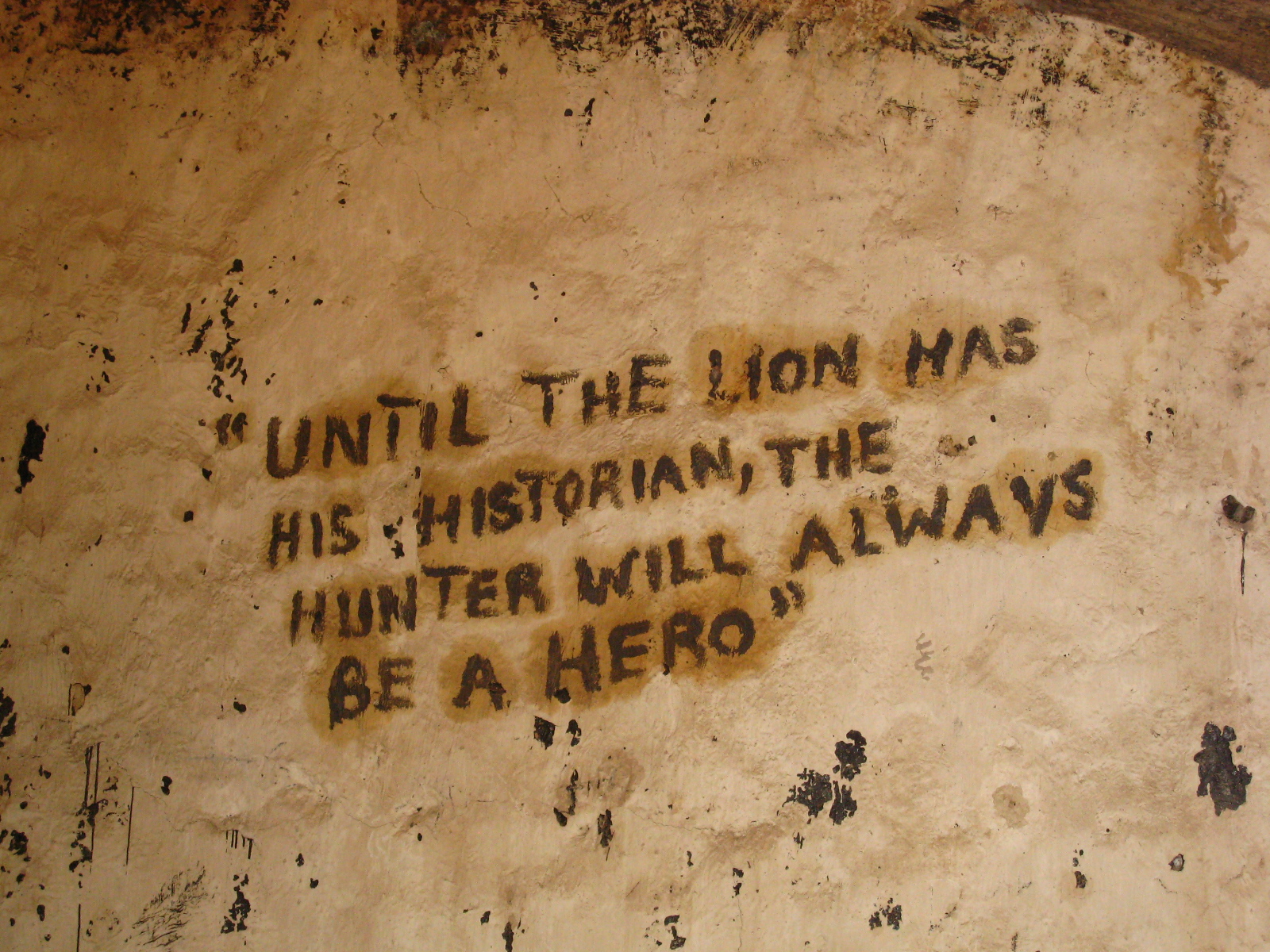

When I asked him what he would teach if he had full freedom, Francis instantly named the First Anglo-Ashanti War (1823-1831), a drawn-out conflict in which the Ashanti empire not only held its own, but which resulted in the death of Charles MacCarthy, the British Governor at the time. “I believe our main issue today as a country is not poverty or disease or any other thing like that,” he said; “Our biggest problem is our inability to figure out our identity. We are stuck between what colonization left us with – a serious inferiority complex – and what modern day reality has taught us.” Teaching the wars between the Ashanti Empire and the British forces, Francis believes, would show students that “the people of old were not ‘enslaved’ to the English, as we are today. That they did not fear them and were ready to fight for what they thought was right. That regardless of their big guns, our people were brave and stood boot to boot with the English.”

“My aim would be to have them understand that they can also do same,” he said, finally. “That we once fought and won against the imperialist!”