In a letter to her agent, Bessie Head acknowledged that her 1974 novel, A Question of Power, had been based on her own debilitating nervous breakdown. She had lived the experiences the book chronicled for almost three years, she explained, before typing them out in a six-month fury. Her protagonist is a South African writer in exile in rural Botswana, tormented by shadowy figures who progressively pry loose her grip on reality. It was out of step with the dominant themes of her time; eschewing post-colonial moralising to centre on a deeply interior and personal experience, Bessie Head retreated into herself to catalogue her battle against herself.

It’s a challenging book from a challenging writer: in her breakdown, she broke down what it means to write an “African” novel. “A lecturer in Nigeria said he found a coolness and detachment in my work that was un-African,” she remarked to an interviewer some years later; “a Zimbabwe student said to me ‘we read Ngugi, Achebe, Ayi Kwei Armah, and we find things there that we can identify with. But with you, we are disoriented.’” And with her, we are disoriented.

Daughter to a white mother and a black father she never knew, Bessie Amelia Head was born in a sanatorium in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa in 1937. While the racist state was consolidating the legal framework that would become apartheid, her mother’s family was placing her in foster care and cutting off contact completely. They never learned that she ended up in a Catholic orphanage so strict that it cured her of religion. Instead, she left the orphanage with only two things that she found valuable: a teacher training certificate and a love for the comfort and solace of the written word. “A career in writing began with a love of reading and a love of books,” she would tell an interviewer, “a feeling for all the magic and wonder that can be communicated through books.”

She couldn’t escape writing. She tried teaching, but despite the promise of financial security, she was unable to give it up. And along with her books, her urge to make sense of her life under apartheid, in exile, and in her own mind fuelled an incredible energy for letter writing. She was an insatiable correspondent, whether writing from her home in District Six in Cape Town, or in the two-roomed house in Serowe, Botswana she called “Rain Clouds.” Some of her correspondents loved to receive the six or more neatly-typed pages she’d send in response to a single page; some found it overwhelming and quickly demurred. You can get the broad contours of her life from books—particularly the 2007 biography by Norwegian writer Gillian Eilerson, Thunder Behind Her Ears—but it’s in her letters that one of Africa’s most captivating wordsmiths bleeds her vibrant heart over the page.

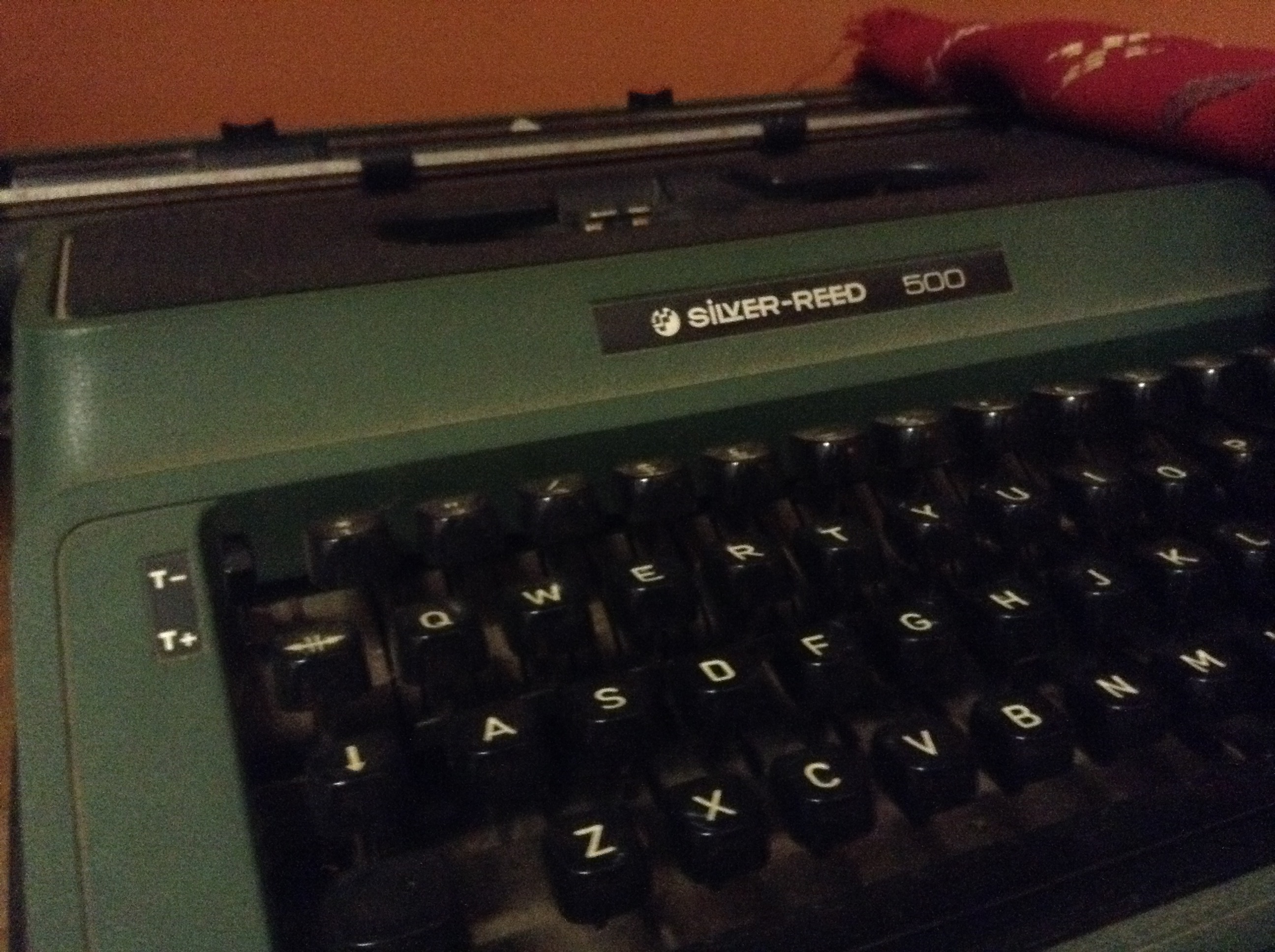

Most of her letters live at the Khama III Museum in Serowe, a small unassuming building, in the illustrious company of the papers of Botswana’s best-known political family. Archivist Kana Tlhaodi told me that most researchers come for the Khama papers, which document Botswana’s political history from pre-independence to the modern era. But one or two researchers a year come for Bessie. They are usually keen to read her alongside Nadine Gordimer and Doris Lessing, she said, as examples of women’s writing during the apartheid era; most of the interest is in Head in the context of race and gender. But Head’s letters show so much more than the times in which she lived. She shows you herself: she was her own greatest champion in a world that repeatedly knocked her down, and found immense relief in pouring her soul into her little green typewriter.

Amongst Head’s earliest correspondents was the African American poet Langston Hughes. At the age of 23, Head had been living in Cape Town, writing full time and dabbling in anti-apartheid politics, and so she wrote to him hoping for advice and support for a book she was developing about her experiences with the apartheid state. He responded but not helpfully, telling her he was too busy (and too poor) to do more than return her admiration. After ignoring two more of her letters, Hughes asked his agent to deflect Head with the excuse that he had a book coming out and simply could not respond.

She never wrote that book. After joining Robert Sobukwe’s radical Pan African Congress (PAC), her home was violently searched and she was arrested with a friend for sharing “seditious material.” Though she responded with stubborn defiance (“I refuse to live in terror,” she wrote to Hughes in 1960, “and if there is a second search, the security police should really have something to read!”) she was shaken by the experience. She remained active through the Sharpeville Massacre in March of 1960, and Sobukwe’s subsequent detention, but she realized that she didn’t have a taste for direct confrontation. “I knew some time ago that I am a useless kind of person in any liberation movement or revolution,” she would write later. But as she had told Hughes that year, her writing “was nurtured by such a feeling of desperation, absolute frustration and a deep sense of isolation, of not belonging.”

And so her writing endured, survived, was even shaped by her rejection of (and by) movement politics. “I met too many horrible types of voracious people in that political party and disliked them,” she wrote in a letter to Sobukwe. She survived a sexual assault by an artist in the movement, an event that seemed to permanently sour her on men, especially her husband, “a useless sort of man” as she described him in one of the many sharp and disparaging letters she wrote both to and about him. (“I can tell you from experience that the male species is sharply divided into monsters and fairly decent men,” she wrote to Alice Walker in 1976, “I know the monsters thoroughly and backwards and everything and I also know that you make no decent arrangements with a monster.”)

When the tightening vise of South African racism made it impossible for Head to remain in South Africa—and when her marriage finally collapsed—she fled with her son to Botswana in 1964, securing a teaching position in the rural village of Serowe. There was no place for her in South Africa; two years after she left, her home in District Six would be demolished under the Group Areas Act, which rezoned non-white neighborhoods for occupation by whites; South Africa would not issue her a passport but she was gladly given an exit permit, a system allowing non-white citizens to permanently give up their citizenship in exchange for escape. But though Botswana proudly claims her today, it would take fifteen years of applications before Botswana would give her citizenship. “I have lived in Botswana for about nine years,” she wrote to the Refugee Officer in 1973, by then, in despair; “I do not need a travel document for myself. Dead bodies don’t need travel documents. They just have to be buried.”

Her most productive period was the twenty-two years she spent in Botswana, in exile. Having lived entirely in cities, the transition to rural and isolated Serowe was difficult. Though she was neither, villagers thought she was wealthy and white; she struggled with the culture of small-town gossip and quickly quit teaching. Only a lifelong friendship with Bosile, a local woman she met as part of the Boteiko Agricultural Project—and with Patrick van Rensburg, who ran the agricultural and self-help project that taught modern farming skills to the rural community—began to alter her experience of the place. It suddenly became a place of fascination; she was captivated by the spirit of collaboration and the simple joys her colleagues found in a good harvest or a successful build. Despite the overwhelming challenges of statelessness, in 1974 she would turn down the opportunity to migrate to Norway, electing, instead, to remain in Serowe and write.

This was the period when she published When Rain Clouds Gather (1968), Maru (1971), A Question of Power (1974), The Collector of Treasures (1977), and Serowe: Village of Rain-Wind (1981). These books were reasonably well-received by critics and they did moderately well commercially. But she knew she was brilliant. “I am a permanent asset to Heinemann,” she wrote to her agent; “my beautiful books are going to live beyond my lifetime.” But the knowledge of her own powers was not enough; she demanded recognition and dared the literary establishment to ignore her.

In a letter to Sobukwe himself, she reflected on her time in the PAC: “I found in many ways that I was not basically a politician, though circumstances in South Africa make one some kind of political thinker…my first book was really to free myself of a sort of prison and to look more deeply at Africa’s destiny which I hope will also be the destiny of mankind—a wealth of humanity and a richness of culture, without the dark taints of class arrogance and power-mongering.” And from her unremarkable corner of Botswana—alongside her novels and short stories—she wrote assiduously to more commercially successful writers around the world, asking for help and support—and, when things were bad—for money. Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Nadine Gordimer, Nikki Giovanni, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Langston Hughes, Ngugi wa Thiong’o and others all received letters from Head. “Well, here I am walking in,” she wrote to Morrison in 1976, “if only perhaps to let my hair down and have a good cry. This letter is going to go on and on, so complicated have my affairs been.” Letters allowed Head to escape and make sense of her frustrations.

Only Walker responded to Head with warmth that matched her own. In 1976, when sharing the details of an upcoming spread in Ms. Magazine where she was an editor, Walker wrote, “I think of you, your beautiful soul and spirit, your beautiful and holy work/life. It sends me into a rage…”

“I am just tired of all the efforts I made on my own,” Head wrote to Walker in 1974, “the uncertainty and the doubt of working in solitude, the drain of offering a certain kind of love that never seems to be returned and the relief at finding someone else with that kind of love too.” Walker sometimes found Head’s intensity intimidating. “I want to be right, for you,” Walker wrote in 1976; “to be perfect. But I’m not perfect. I am terribly confused and untogether…” But Head responded warmly to the recognition that her friendship was demanding; she confessed her own frailties and the depths of her breakdown to Walker in a way that she didn’t with anyone else. “It is a great joy therefore,” she wrote in a three-page letter praising the essays that Walker had shared with her, “to simply offer homage to another living human being, like the homage I offer you.”

Head didn’t write these letters as a fawning, adoring fan. She genuinely wanted intellectual companionship from her correspondents. She was generally tolerant of their intense schedules and lackluster response, but when she didn’t like the direction of the correspondence, she let them know. After a brief, unsatisfactory correspondence in which an African American writer turns out to be remarkably self-absorbed, Head writes “I prefer people to stars and shit like that. I warned you that this is not my world, so I tell you we call it a day from now on. If you send me your fucking claws, I’ll send you your fucking claws back.”

In Head’s detailed letters to agents and publishers, she shows herself to be a tremendous champion of her own work, anxious for commercial success but unwilling to compromise in achieving it. “I am anxious to know if I have a best-seller at last,” she wrote in 1982 of Serowe. She was also very conscious of avoiding exploitation. When she felt a publisher was underselling her work, she “was dismayed indeed at the meanness of the offer for my autobiography,” she explained to her agent; “I cannot live on £2500 for a year. Please accept NOTHING less than £6,000 and press for more if possible.”

She initially welcomed contact with universities but she cut them off when she felt she was being exploited. Apartheid universities in South Africa were more fascinated by her otherness than by the quality of her work; she became resentful at being exploited without remuneration. “I was abused by some lecturers of the University of the Witwatersrand,” she told her agent, in 1985, while declining an interview; “I had one of my private papers stolen and one of my friends tampered with in an unpleasant way.”

Commercial success eluded her, and poverty took a toll on her health. Her books were selling, but Head was grossly mismanaged early in her career, and she never fully recovered from the financial mess her early agent put her in. The agent had lost some of the rights to her better-selling works but she was sitting on Serowe and Botswana Village Tales – two Africa-centric manuscripts that she struggled to sell in London and New York’s inward looking markets. Only an unshakable belief in her own worth kept her going, and after she got rid of the dodgy agent, Head briefly and vehemently represented herself. “Now I want from Heinemann £6,000 commission for my autobiography,” she wrote to James Currey, her publisher in 1984, “I also want from Heinemann a gift of £6,000 to renovate my house and start a seedling nursery. Find it all, James. Find it. Heinemann will be damned if you don’t.”

By 1985, Head had found a new agent but was still struggling to make writing pay. “The roof in my house leaks so badly that when it rains, the rain pours into the house” she wrote to her new agent that year, “Last year the pipe burst with age and heat. … I draw water with great difficulty to my house. I have a weak back and cannot carry heavy weights. I have been in hospital twice for severe back pain.” Her slipped disc forced Head to seek an overdraft while she waited for various cheques to clear and to sell the rights to her non-fiction book on Serowe. “I broke one of the discs of my back lifting a heavy drum of water,” she would explain to a bank manager, “unable to draw water for my home and need an immediate water connection. Could I have an O.D. [overdraft] of P200?”

Her mental health was fragile. “I just want to try and get out of here before I die,” she wrote to Nikki Giovanni about the stress of statelessness in 1974. “Once that problem is solved, then I might even attempt suicide, my life is of so little value to me.” Life kept coming; her son’s father reached out even though she had explicitly asked him not to, and her mother-in-law attempted to communicate with her young son without her permission. “Your role as father of the child is entirely in your own imagination,” Head responded; “If she still comes here I shall certainly stab her to death or try to kill her with my bare hands…So bring your gun. God I hate you. I hate your mother, bitterly and deeply.”

By 1984, Bessie Head was on the cusp. The Botswana government finally gave her citizenship and she was looking forward to teaching in the US, where she could work with Alice Walker and Maya Angelou amongst others; she changed agents and in 1986, she recovered the rights to her catalogue. Heinemann gave her £7,500 for her autobiography, far above the £6,000 that she had demanded. Head was excited about the project. “There is no sex or love for these 46 years of my life,” she wrote in 1984, “but rather a rich spiritual discipline which I feel is now finally coming into its own.”

But on 17 April 1986, two days after she was found ailing by a close friend, Bessie Head died of hepatitis. With no letters to illuminate it, her death remains as obscure as her birth. She was often seen with a beer bottle in hand, but Scobie Likuthule, curator at the Khama III Museum and a close friend of Head’s son Howard, does not believe that she had a drinking problem. More likely, she picked up the infection at her farm and failed to seek treatment for it until it was too late. Her son Howard was in Canada with his father and Head suffered alone for some time before a close friend found her, already too far gone for treatment. Howard never married or had children, and so when he died in 2010, her legacy passed into a trust established in her name.

Today, writers and readers stand to learn a great deal from Head’s work. No one writes about rural Africa with as much heart and complexity – at least not in English. “Like all his clan, the Tswana doctors,” she writes in ‘Witchcraft’ a short story in the anthology ‘The Collector of Treasures’ “Lekena had considerable dash and courage. They were like gymnastic performers of a very imaginative kind and for centuries, in their tradition, they had explained the world of phenomena to themselves and the people.” Africa religion and traditional practice are so often otherized that it’s hard to imagine someone else describing traditional mystical practices in such an effusive way. But this is Bessie Head. If her characters face some of the same situations as Achebe’s Okwonkwo or Ngugi’s Waiyaki, they do not collide with “colonialism” and “modernity”; they are not stick-figures on a grand historical tableau but fully formed humans grappling with the unexpected with remarkable depth. Head gives her characters the depth and gravitas often denied to rural life in Africa, the kindness she so rarely felt. Perhaps because she sensed she would never feel it, she gave it to her characters. “I know where I stand with ruthless, terrible cruelty,” she wrote to Walker, “I don’t like the knowing I have because it isn’t a world that is favourable to survival of any kind but it has its value and one day I might be able to set it into proper perspective.”

Today, as when Head wrote, too much African fiction is constricted by a sense of what is “African” enough. But Head was uninterested in writing for anyone other than herself; “The best and most enduring love,” she once wrote, “is that of rejection.” As Helen Oyeyemi observes in the foreword she wrote for an edition of Maru and When Rain Clouds Gather, Head struggled with the “desperate guess work” of trying to write as an African, until she threw off the burden. And so, for writers like Oyeyemi—who reject the burden of anthropological writing—Head offers a north star. “I believe in the contents of the human heart,” Head once wrote, “a silent and secret conspiracy against all the insanity and hatred in mankind.”

“An isolated goddamn outsider trying to be an African of Africa,” Head once labelled herself, a city girl stuck in a village, a South African forced to build a life in Botswana, a woman outside traditional norms of womanhood, an intellectual living in a village with limited basic education at the time, and a human being who struggled with mental ill health almost all her life. Yet while her mental health is often described as “fragile,” she was a sensitive artist who managed to retain a depth of feeling for humanity in the face of some of the ugliest chapters of human history. She lived a life apart, deprived, often along (“You know perhaps nothing about a little village,” she once wrote, “in an African village it’s goddam deep and dangerous.”) She had no amusements other than writing; there were no jazz bars, no dance parties, no speaking engagements, and no libraries or salons to kill time. And so, letter writing was Head’s primary connection, a lifeline and a means of surviving the lack of what other artists could take for granted. She survived. She found a way to love. And she sent us her letters.