The first thing you might notice upon arriving at the Salt Lake International Airport is the constant, desperate welcome party. Clouds of people wait expectantly at the entrance to the terminal, cheering and holding homemade signs. “WELCOME HOME, SISTER!” the wobbly purple letters might announce, the sign dropping to the floor as a young woman in a long skirt is embraced by a weeping parent. Nearby, there might be balloons and cheering as an even younger-looking man in a three-piece smiles weakly. His grandparents awkwardly hand him flowers. Between one and ten of these interactions might be occurring at a time within the same twenty foot space. There might be airhorns. There might be forced laughter, or confetti, or stacks of cups held in anticipation of chain-link messages to come. At the same time, you and other regular travelers, on business or passing through or on the way to somewhere less monumental, slip in and around the dramatic scene silently, striding toward the exit or the solemn drivers with their smaller, more staid welcome signs of their own. Ahead of you lies the slowly swelling skyline of Salt Lake City and the immense mountains that hold it.

In many ways, this airport, as well as the city that it services, are a matching pair of contradictions. Here’s one: it’s hard to talk about this place without talking about The Mormon Church, the sprawling and proselytizing global sect of Christianity that ushered the vast and bleakly beautiful valley surrounding the Great Salt Lake into cityhood and away from native stewardship over 150 years ago. It’s certainly impossible to take a walk through the Salt Lake Airport without seeing the Church’s institutional influence; the ongoing welcome party in the terminal is buoyed up by kindly aspirational posters urging visitors to see the huge, castle-like temple owned by the LDS Church and its surrounding religious sites. But this airport has more to tell you about this place than just making “Utah” synonymous with “Mormons,” or even “Mormons” with “Utah.” Neither is correct. In many ways, this airport, and its arrivals and departures, have more to say about the misunderstandings underneath the surface, about the danger of hubris and the boundless exceptionalist optimism that drove white pioneers here in the 1800s — the same hubris that now pushes streams of snowboarders, coders and venture capitalists into the same place, all getting off planes in the same patch of emptiness.

The airport itself, ASLC, sits in the bleak desert plain about four miles west of Salt Lake City. The city is named for the Great Salt Lake, the largest saline lake in the Western Hemisphere. Its dead orange and blue glint to the west is best viewed, coincidentally, from a plane, perhaps flying Delta. The landscape surrounding ASLC bears much resemblance to most airport-adjacent scenery: buzzing and chaotic freeways, narrowing roads, eerie emptiness, shitty hotels. But to get to ASLC from one of Utah’s bigger cities (Salt Lake City, Provo, Orem) requires you to take a separate exit off of I-15, along the ever-present mountains from north to south. From there, you take a smaller highway west, away from the freeway and away from populated areas, toward the largely unknown zone constituting the saline lake that gave this airport its name. One has the sensation, driving toward ASLC, of moving into an abyss; the area extending behind the airport turns into the jagged peninsulas and tributaries surrounding the lake, simultaneously the core and void of where you’re trying to go.

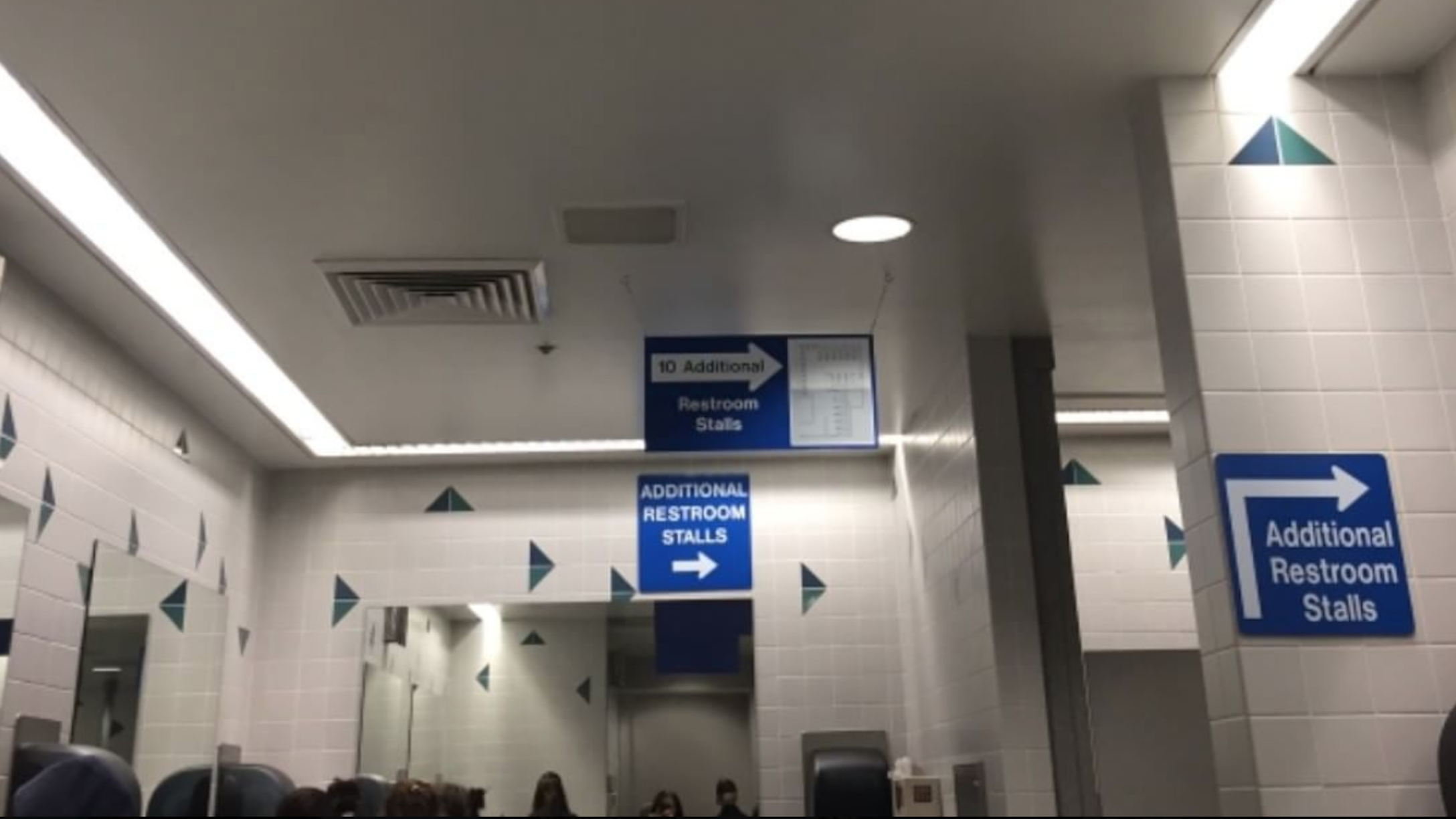

Like many other major yet midlevel U.S. flight hubs, ASLC has suffered a lack of renovation relative to demand, which the clunky, early-‘90s aesthetic carpeting, print and decoration indicate better than even the miles of construction outside. Letters are in chunky bold script reminiscent of driver’s ed films, carpeting and walls clash with the solid blues and bright orange and red overlay that bring to mind a ski lodge, a roller rink, something well-worn, seasonal, and not worth renovating. In tone and style, in fact, ASLC brings to mind the bizarre spaciness and uniquely western American awkwardness of the Denver International Airport, complete with the sense that the terminals might secretly double as nuclear bunkers, if the situation called for it. As if anticipating the crowds of well-wishers coming to greet returning missionaries, bathrooms at the outer terminal include multiple labels and sets of directions for how to access other stalls. ASLC is certainly outgrowing itself, and recent developments have suggested a growing resentment toward the use of the outer terminal and parking garages for families picking up their long-awaited missionaries in style. A massive remodel, to be completed in 2023 at a reported cost of 3.6 billion dollars, is large and jarring enough to suggest the appearance of a new population center. Utah is forced, yet again, to grapple with the question: who do we want to come here?

For better or for worse, this question is a ubiquitous part of flying and walking through ASLC, and of being in Utah in general. The young returnees in Terminal 1 are the proselytizing missionaries for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, which no longer wants you to call it the Mormon Church (but you will anyway). Young believing LDS men are expected to leave home, family, work and study at the age of eighteen or nineteen and work full time for two years without pay, somewhere in one of the 421 proselytizing areas throughout the world. Women are encouraged, though not obliged, to complete this service, and serve for only eighteen months. A majority of Mormon missionaries complete pre-service training in a massive training center in nearby Provo, and are dispatched to their “mission field” from this airport. Upon leaving for destinations that range from Denver to Copenhagen to Seoul to Toronto, most missionaries travel through ASLC. The sight of them is ubiquitous: earnest young guys in suits and ties and women in knee-length skirts, each wearing the signature black name tag advertising their role. Besides missionaries, ASLC is the main port of travel for the lay clergy of the LDS Church, which includes twelve men who are believed to be apostles — spiritual leaders for most believing Mormons.

The Church’s widely accepted narrative about its geographical association with this place is this: persecuted and chased from city to city, early Church settlers finally built their Zion in a place that was empty, barren, and dry, and through combined grit and heavenly intervention, caused it to “blossom like a rose.” Most of this isn’t true, of course, starting with the “empty” part — violent displacement of native inhabitants of the area was, as with other groups of settlers, common, accepted, and whitewashed from popular history. But the power of the narrative remains in place, the basis of the unregulated expansionist economy that continues to rule most of Utah, where all of nature is seen as God’s empty, indestructible frontier.

Salt Lake City, the state’s capital, has expanded to grow at a faster pace, now attracting workers and students from throughout the world in fields like finance, health, and technology. In certain ways, Salt Lake City is the urban haven to which one escapes in Utah after outgrowing the conservatism of suburbia, and the more religious universities to the south and north. Salt Lake is where you go to be in Utah, but not of Utah. As a result of this and other factors, the politics of the city itself have become more moderate than the vast majority of the rest of the state’s solid religious red, and are trending further and further left. The city’s election of the state’s first openly gay mayor was a visible symbol of amplified conversations about the Church’s steadfastly unaccepting stance toward LGBT people and women, especially as a younger generation of Mormon-raised people left the faith. Like many other growing, moderate capitals of dwindling red states, Salt Lake City is a good example of the type of urban-rural divide that will continue to increasingly define state politics in a permanently changing midwest.

Serving 24,198,697 passengers in 2017, a 4.5 percent increase from the previous year, air traffic to Salt Lake City is projected only to increase, as more new residents, interns, hikers and skiers make their way to the area to enjoy new jobs, spacious roads, and a relatively low cost of living. As it is, ASLC still feels crowded and sweaty, as terminals are closed to accommodate reconstruction and traffic ticks slowly up. In five years, a rebuild may coincide with growing changes in the state’s politics, orientation to outsiders, and ability to accommodate endless unregulated reception parties. And as the Great Salt Lake continues to dry up with each passing dry summer, clouds of saline-soaked dust and debris will add to the cloudy fog of poisonous air overhead, a fact of living in Utah, an unstoppable and largely unaddressed public health disaster. But you can’t see it once you get above 3,000 feet.