This is what I know happened.

It was June 5, 2004, and there were just seven minutes left in game six of the Stanley Cup Finals. The score was tied, 2-2. The Calgary Flames were playing the Tampa Bay Lightning, and they were leading the series. If they won the game, they would win the Stanley Cup.

I was ten years old, and I wanted the Flames to win the Stanley Cup. I liked their jerseys. But for the last fourteen years, I have been mad about what happened next. Or what didn’t happen next. Or, rather, what I will never know about what happened next? I have been mad that I don’t even know how to explain why I’m mad about what happened next.

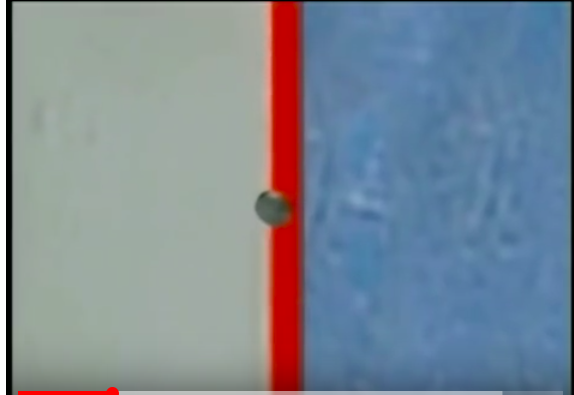

This is what happened next: Flames forward Oleg Saprykin carried the puck up the right side into the offensive zone and cut left towards the net; his teammate, Martin Gelinas, charged down the center, looking for a pass or a rebound. Saprykin didn’t pass and didn’t really shoot, however; the puck slid off his stick and into goaltender Nikolai Khabibulin’s left leg pad, bounced into Gelinas’s skate, and then into the air and back toward the net. At this point, Khabibulin’s right leg kicked forward, made contact with the puck and sent it back outward.

Nothing happened next. The referees had a better angle than the television camera and didn’t call it a goal on the ice. Play continued.

It would seem that nothing had happened.

Then again, it was hard to tell what had happened, or what didn’t. At full speed, ice shavings are flying and there’s a lot of movement. The replay makes it look like the entire puck crossed the entire goal line; the replay make it look like it should have been a goal, like the Flames should have gotten a 3-2 lead, and should have been seven minutes from winning the Stanley Cup.

But it wasn’t called a goal. Nothing happened after that, either; nobody scored for the rest of regulation and when the game went to sudden death overtime, nobody scored through the first overtime period. Then, thirty-three seconds into the second, Lightning forward Martin St. Louis caught a rebound off Flame’s goaltender Miikka Kipprusoff’s pads and snuck it between him and the post. The Lightning won game six 3-2, and then the Lightning won game seven and won the Stanley Cup.

There is no disputing any of this. It is certain. What I still don’t know—what nobody knows—is whether, in game six, the entire puck crossed the entire goal line with seven minutes left.

This is what made me mad, for 14 years. Not that the Flames didn’t win the Stanley Cup. Not that because the Flames didn’t win the 2004 Stanley Cup, Jarome Iginla, a favorite player of mine, would eventually retire without his name etched into hockey’s championship trophy.

I’m mad we don’t know. How can we not know?

They tried to figure it out. Long after it could be fixed, they tried to figure it out. ABC put up a three-dimensional rendering of the play, during the game seven broadcast, a terrible 2004-era CGI animation made by a Canadian computer-generated imagery company. It looks bad. The animation shows that the puck did not cross the line. It was not scientific, admitted color commentator Bill Clement. They made certain assumptions, he acknowledged.

There are people who take this graphic as proof, but I am not one of them. The height of the puck is a problem. It looks like a goal on the video replay because there is a lot of white in between the puck and the goal line, which would be true if it was in the air or had crossed the goal line, or both. But if you don’t know how high the puck is—if you must make “assumptions”—then you don’t really know how much white should be between the puck and the goal line, do you? You don’t know if it should have been a goal. You don’t know if it shouldn’t have.

Sports are supposed to provide closure. The games end. The seasons end. It all turns into trivia, numbers, states, lists of champions and standings and final, stone-graven results. You’re supposed to know. That’s the point.

I come from a family of sports numbers people. My parents are accountants; my little brother has degrees in Engineering and Statistics. We are a sports family; we are a Jewish family. When you tie it all together, you get a family that argues about the facts of sports a lot, and the facts matter to us. We are proficient at taking what happened and turning it into an argument about why or how, and these conversations get derailed when nobody knows what happened or didn’t.

Sports don’t matter, but they matter to people, which is almost the same thing.

And yet, one of the most agonizing things about sports is how often you don’t know, how often the result diverges from what you’re certain you saw. And how this matters.

In some sports, after all, the rules are metaphysical. I remember in 2015, when a Dallas Cowboys receiver made a spectacular catch and the catch was overturned on review. “Although the receiver is possessing the football, he must maintain possession of the football throughout the entire process of the catch,” the referee, Gene Steratore, explained after the game; “In our judgment, he maintained possession but continued to fall and never had another act common to the game.”

“Another act common to the game” is a phrase from Rule 8.1.3 of the official NFL rule book; for a catch to be A Catch, the player must maintain control of the ball long enough to enable him to perform “any act common to the game,” which the rule book helpfully glosses as “maintaining control long enough to pitch it, pass it, advance with it, or avoid or ward off an opponent.” He does not have to actually do these things. He must simply have control of the ball long enough that he hypothetically could.

In the NFL, in other words, catches are epistemological questions. Everyone saw him catch it. But did he Catch It? Sometimes it looks like one thing happened, when it really didn’t; this is the nature of the NFL. To know What Really Happened, we must rely on the official word of the referee, who can explain that what happened happened not because what else could have happened didn’t happen, but because there wouldn’t have been enough time for it to happen anyway.

Football fans have to make this compromise: something that looks and smells and walks like a catch might not be a Catch. Why? The Rules. In football, that’s the difference. The Rules outweigh the Reality. And when it comes to football, I have made that compromise.

But I cannot make the same compromise for hockey. I will not. Did the entire puck, a physical object clearly defined, cross the entire goal line, a physical marking clearly defined? If yes, it’s a goal. If no, it’s not. This isn’t a dispute about the rules; it’s a dispute about what happened.

A quirk of “these times” is that despite all our attention, it feels like we never really know what’s going on. If this was true in the past, it feels truer now. Decisions impacting our everyday lives are made behind closed doors, and we never learn why: grocery stores stock this and not that, the stock market rises or falls, studios greenlight one show and not the other; the President calls for a drone strike in Iraq and not Pakistan, a job is lost or gained, a health care claim is covered or not.

In theory, there’s a logic to it; in practice, we don’t get to know, not really. We guess.

Sports should be different. Played in front of millions of people, in front of multiple cameras, we all see it all. And in the championship round of a professional sports league, when everyone sees everything, that’s when we get to really see it. All the big and important stuff, we watch every bit of it happen. Us watching it is why it happens; they play it so that we know.

To get to that point, for the puck to bounce off a skate, and for us not to know whether the whole puck crossed the whole goal line?

I don’t know how we don’t know. I’m mad that we don’t know and I’m mad that people think they know. They don’t know, neither do we, and we never will.

***

Still Mad is a regular Popula column, in which we explore the things that still make you much madder than they have any right to make you, somehow. Goddammit.