It’s so easy to dismiss the way the internet fixates on dogs and cats that we do it almost reflexively; why, we demand, is a prime minister or a president posting cat pictures? The incongruity is so obvious that it’s barely worth spelling out (what has POLITICS to do with stupid animals, etc). And behind all the grand claims made in the name of the internet–building community, breaking down barriers, revolutionizing business, blah blah blah–we find the awe-inspiringly humble fact that one of the things people like doing best is posting pictures of their animals. (I know I certainly do.)

We shouldn’t dismiss that. It tells us something about that strange first-person plural we call by the names “we” and “us.”

Yet if “the internet” is fascinated with animals–the cat pictures! The dog videos!–then turning into a feature of the medium is another way we might find ourselves quietly contemptuous of this bit of crowd-sourced wisdom that we might otherwise pay the most grave respect; if we ran it through an algorithm and made it “data,” after all, it would become the something that most resembles truth in this internet of things. People like to say that we are “post-truth” but we are certainly not post-data. Truth is bullshit, but data is money. We respect the “we” formed out of the latter–a “we” constituted through commodification and profit–but the “we” formed out of the former tends to be a them.

I’m not sure if I’m saying that cat pictures and dog videos resist commodification, though I’m certainly asking the question because it feels plausible and because I want it to be true. But when we’re not marveling at the awful majesty of the crowd’s wisdom—oh, the algorithm!—and hooking literally every part of technologically modern life up to it, we’re tossing off dismissive comments about how the internet is only for posting cat photos, laced with contemptuous implications about the sort of person who would engage in such stupid frivolity.

These are probably all “we”s that we should be skeptical of, as skeptical as we should have been when Facebook informed world media that the masses only loved video and anything as banal as writing needed to be let go. Making claims on the “we” is powerful, and so power is exerting by making those claims. But just as power is the work of changing the thing the power is exercised upon, any claims made on that basis are flawed by nature, a reflection of the aspiration to change rather than describe. Facebook’s claims on the “we” were made in order to bring into being the world they wanted to see, an aspirational pivot to video that was to happen upon the claim that it already had. They told us what the we was, and we seemed to believe them.

As an editor at Popula Dot Com, I often find myself suggesting to people that they think about turning the “we” into a more specific sense of the “I”: tell me what *you* think, I sometimes say, and feel and do; when you make that I into a “we,” it not only loses definition, it becomes vague in a way that scales up and down too easily. Claims on the “we” can be a lazy way of making a tranche of society—yours—stand in for the whole, and we here at Popula Dot Com are more interested in the weirdness of the tranche than in the mirage of the whole. So a healthy distrust the “we”–along with respect for its power–seems like a good place to start in describing what the “popula” means in Popula.

That we do seem to like cats and dogs, however, is the sort of crucial algorithmic insight that only the internet could provide, however; if you peer into the soul of the crowd with me, you will see, as I have, that there’s a lot of that stuff online. I guess that’s the sort of thing we’re into, or at least I am. And, of course, I’ll admit that there is something peculiar to the medium, here; if I didn’t have twitter or Facebook, I probably wouldn’t take pictures of dogs that aren’t mine—or not nearly as many—and if I didn’t have twitter, my first impulse when I see Pepita or Pequod do something cute wouldn’t necessarily be to take a picture. It’s only because I know that, online, there is a community of people that will want to see these pictures—or will endure them in silence—that my brain has been trained to react in the particular ways it has.

The same is true of food: before the internet, people obviously never enjoyed food. But if the internet—or social media, I should say—only amplifies and then reiterates and incentivizes pre-existing behavior, then there probably is something to the underlying “we” that’s worth knowing. The digital soylent of the internet is made of people, is it not? You can learn something about who we are by taking cell-phone camera photos of this meal; by converting it into a they—not “us” but “the internet”—we can take a step back and see something that we couldn’t if we were regarding us.

We can see, for example, that people like animals, that they’re good dogs, Brent; without crowdsourced data, we’d never have known this pertinent insight.

This is good information to have. It’s good information to have because, we-the-human are destroying the world’s biomass in all sorts of ways, not least of which is that we eat a lot of animals (after killing them); it’s good information to have because when we are at our most dour about humanity, our most cynical and contemptuous and pessimistic, we’ll assume the worst of ourselves and say, more or less, we are awful. Andwho could argue? Our aggregate sucks. The soylent you can make out of humanity by transforming us into data—or electoral results—is anything but uplifting. But then again, it’s literally the point of soylent that food made out of people is a bad thing to make; maybe only Silicon Valley would forget that.

In recent weeks, it has warmed me to discover that the Chilean people—as a slice of human I’ve been observing for a still-anecdotal-but-not-insubstantial period of time—really like dogs, not only enduring them in their cities and loving them in their individual homes, but caring for them as a mass. Of course, there are some Chileans that don’t love dogs; I saw a woman yelling at one on the street (in the shadow of the glittering Costanera center, the grand mall that shows how Chile has turned the corner and become a first world nation and so on). But let’s move past that anecdote to the many that fit the story I want to tell about them, and after all, that’s not the “we,” that’s an individual; as interesting as the individual is—on a Sunday morning in the upscale downtown of Santiago—it’s an utterly replicable experience to wander around a Chilean city and see a lot of really healthy-looking feral dogs, sufficiently well-taken care of by individuals who blend into the mass without taking individual ownership.

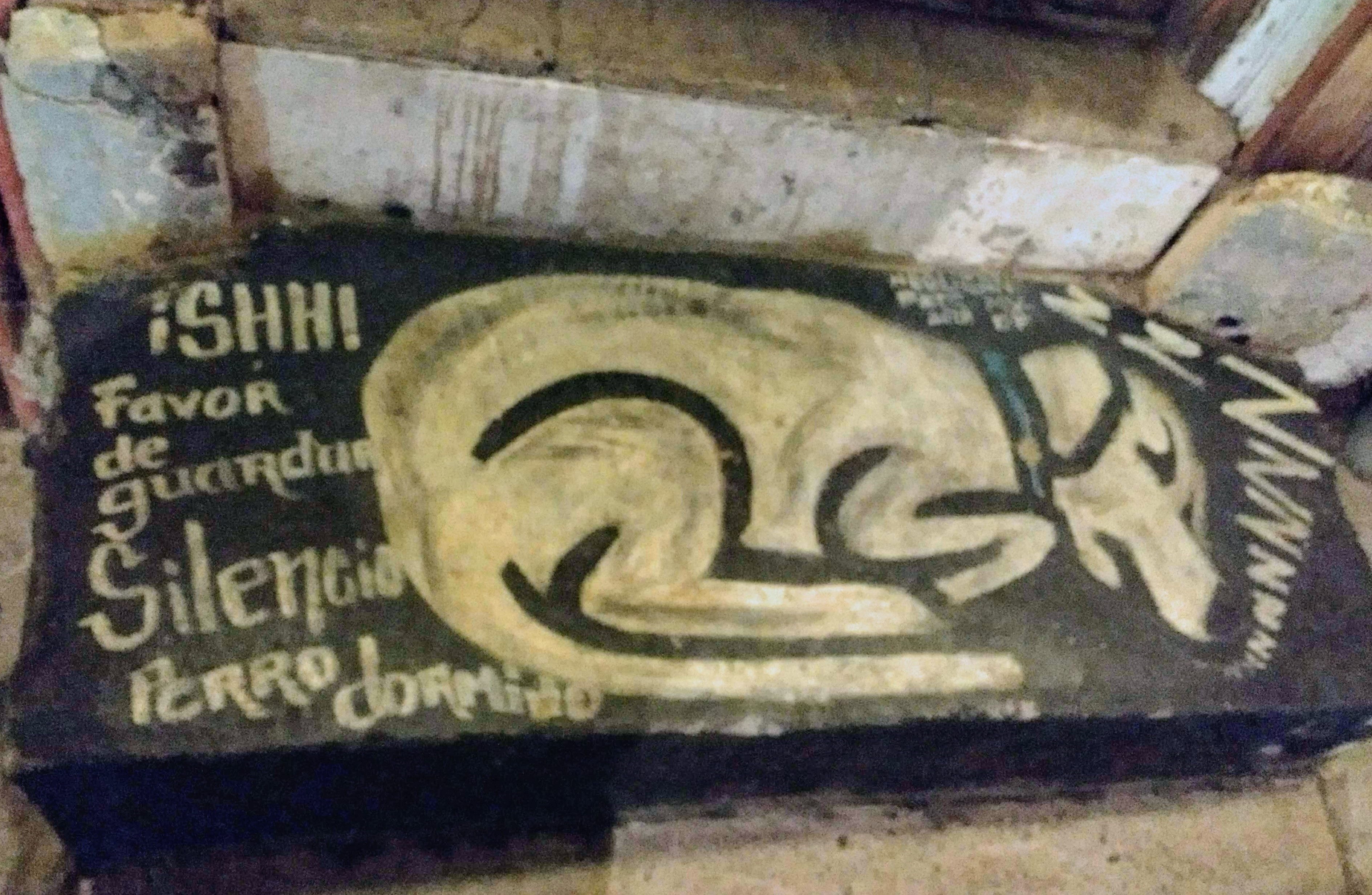

You’ll see dogs with coats, knitted for them by random strangers. You’ll see them sitting without fear in the middle of crowded bus stations or doorways, and everyone walks around them; you’ll be in a café and a dog will come in and roll around on its back until someone gives it ham, which happens, and then it leaves peacefully and happy. You’ll see messages on doorsteps instructing you not to beware of a dog that will shriek at strangers on the border, but, instead, please, try to be quiet and not to wake it from its slumbers. You’ll see dogs who like strangers, and want attention, but who don’t seem to want anything more than that; they accept the friendship offered on the free marketplace of affection and then they wander off.

It’s good to notice this sort of thing, because you might otherwise talk yourself into thinking the worst of us; you might let yourself hear only the Hobbesian jungle story about people, where we’re all animals and animals naturally attack and eat each other, and you can’t trust any we larger than your nuclear family. Economics is always based on these very particular stories about nature–a war of all against all, instead of ecosystems defined by co-existence and gentle mutuality–but while Chicago Boys will be boys (and Margaret Thatcher is so good at telling you that society is what there isn’t). And look, maybe the real attraction of animals online is that they are sufficiently apolitical that we can all agree on their goodness; in an age of resurgent neo-fascism, we can distract ourselves from the war of all against all in human society by loving animals together (and not thinking about how the sausage gets made).

Even so: it’s good to look at a place like this and think about what kinds of media made taking care of stray dogs something that everyone knew to do, and wanted to. It’s good to look at this anecdotal observation, not-quite-data, and observe that while my country does not like stray dogs, in the mass, this country certainly seems to. And in a way, I can do that because it’s a place that’s not my place, where close acquaintance hasn’t blocked my sight; in a place like that, I’m not tempted by the “we” to let familiarity breed contempt. Here, I can almost think that maybe the mass of humanity was never the problem, but, rather, what was done to it, by the machines that grind us up into feed and feeds.

Aaron Bady