Translated from Hebrew by Josh Friedlander

A few years ago, at the beginning of a French course I was taking at Tel Aviv University, a new student entered the classroom. His face looked familiar. “It’s Dan Roman,” I murmured to myself. Roman was a footballer who played for Maccabi Tel Aviv, my beloved team. In 2008, he’d set up a heroic, last-minute winning goal against Hapoel in the Tel Aviv derby. I sat with the Maccabi Ultras that game, a devoted and fanatic supporters’ organization composed of a couple hundred half-naked teenagers. The memory of the obscene gestures I’d made toward the Hapoel fans at the final whistle was still wonderfully fresh.

Roman crossed the classroom, considered his options, and finally went for the empty seat next to me. I nodded politely and decided to control myself. A second later, I heard myself saying, “You’re Dan Roman,” while pointing at him from a distance of mere centimeters. “I sometimes sing your song during games,” I added. “Dan Roman Dan Roman Dan Roman Oooooh, La La La Dan Roman.” I smiled. He shifted uncomfortably in his chair.

One of the fascinating things I discovered in the long conversations I forced on him in breaks between lectures that year was the enormous gap between the emotional way that supporters see and think about football, and the language and concepts with which the players and coaches themselves understand the game. Every match that we spoke about suddenly split into two totally different games. While I talked about willpower, battle, and abstract psychological motives, he spoke about territory, movement, and concrete tactical challenges. It became clear that, despite having seen thousands of hours of football, I understood almost nothing about the game. As a supporter, my concepts remained very basic and unsophisticated when compared to those used by the people playing. This wasn’t so different, I came to realize, from the gap between readers and writers/scholars in literature. So many people have been entranced by the plot in Balzac’s novels, yet how many of them have thought about the text the way Roland Barthes does in S/Z?

I showed Dan the book Atlas of the European Novel, by the Italian literary theorist Franco Moretti (who has recently been accused of sexual assault, abuse, and rape by a number of former students). In one chapter, Moretti creates maps tracking the movement of the characters in the Paris novels from Balzac’s Human Comedy. By mapping, he claims, we can uncover various narrative and thematic patterns invisible to someone reading the book “normally”—such as where in the city Balzac’s protagonists tend to start the plot, where they pause to daydream, and where they are when the story ends.

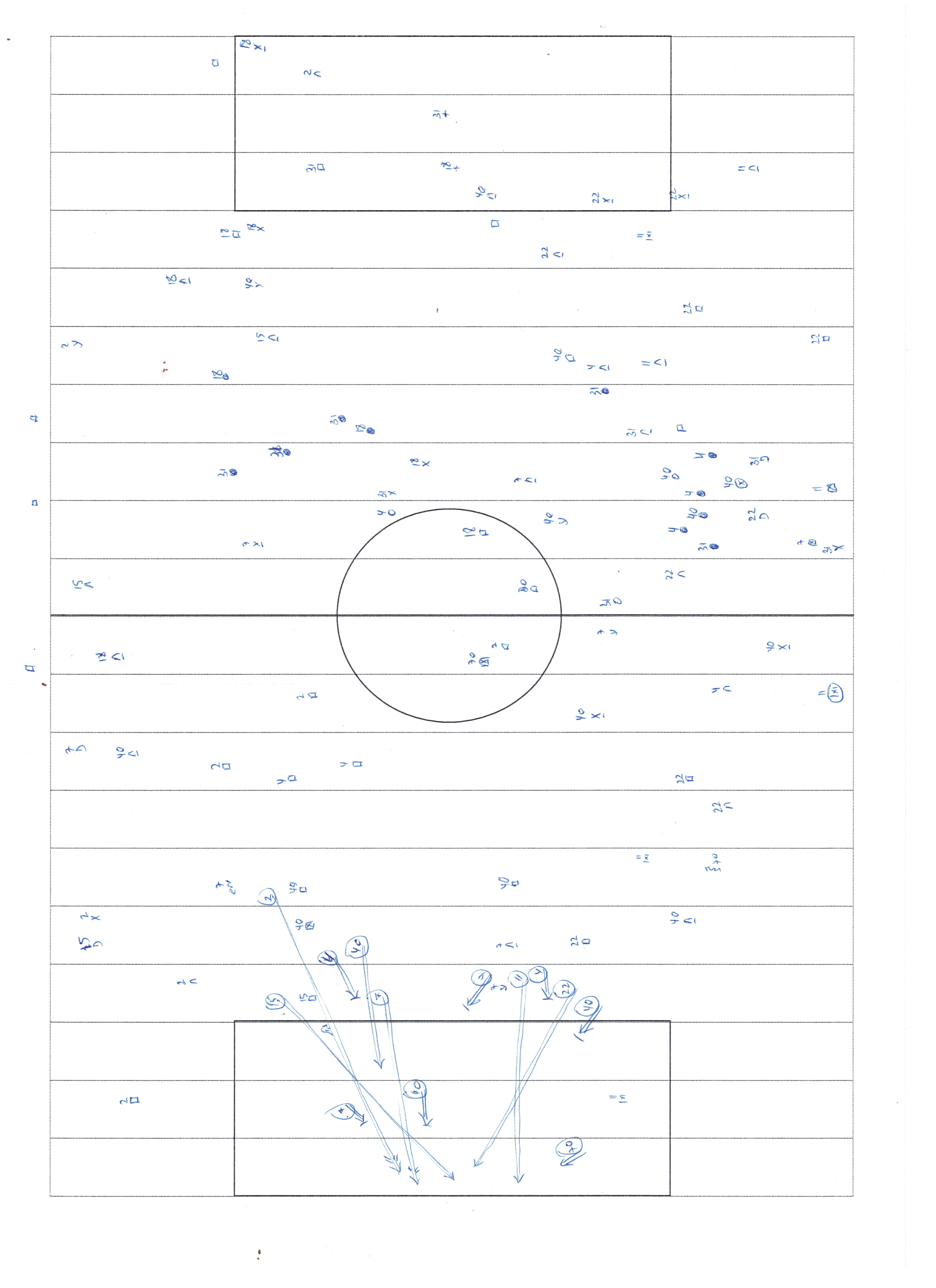

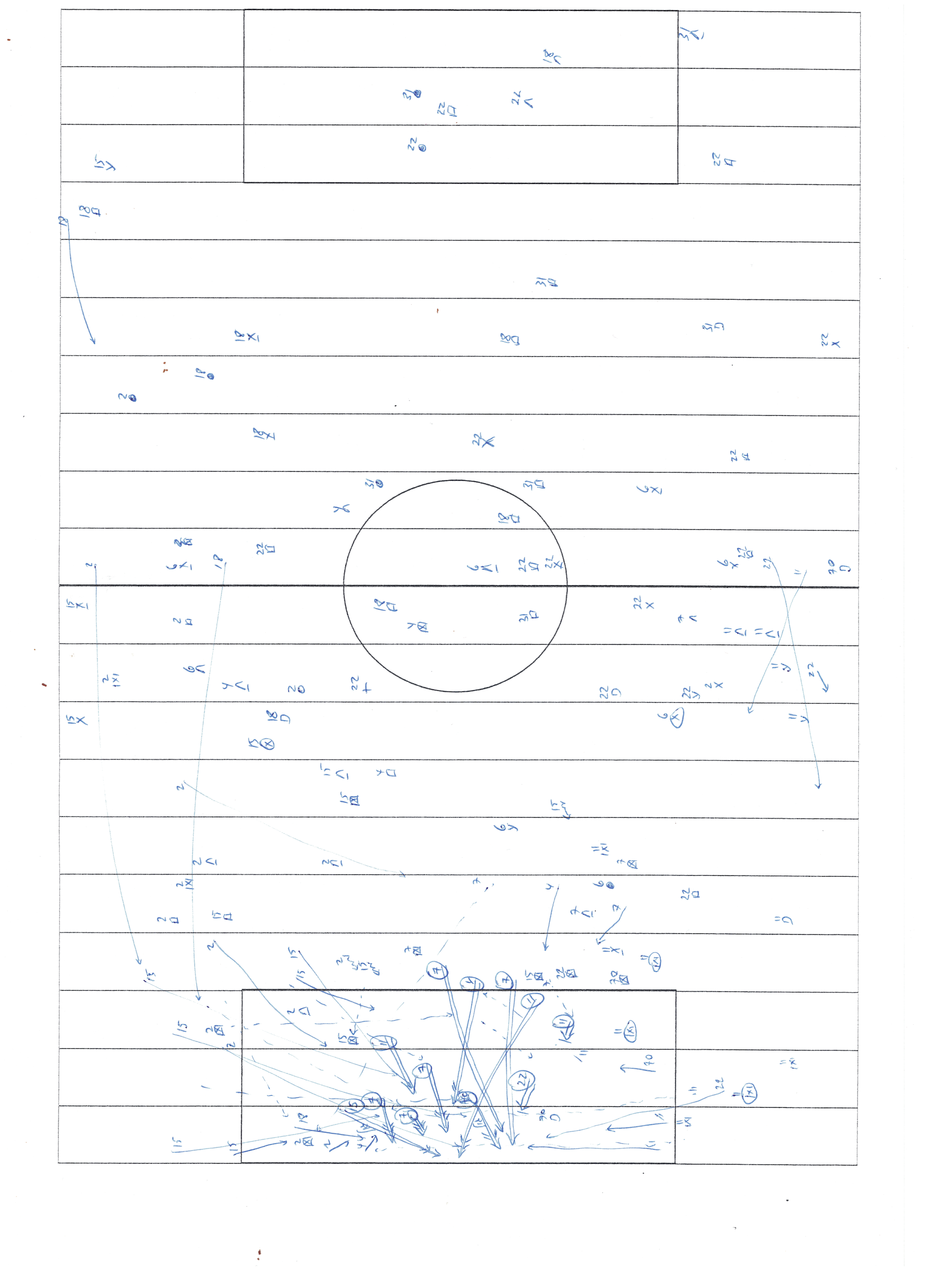

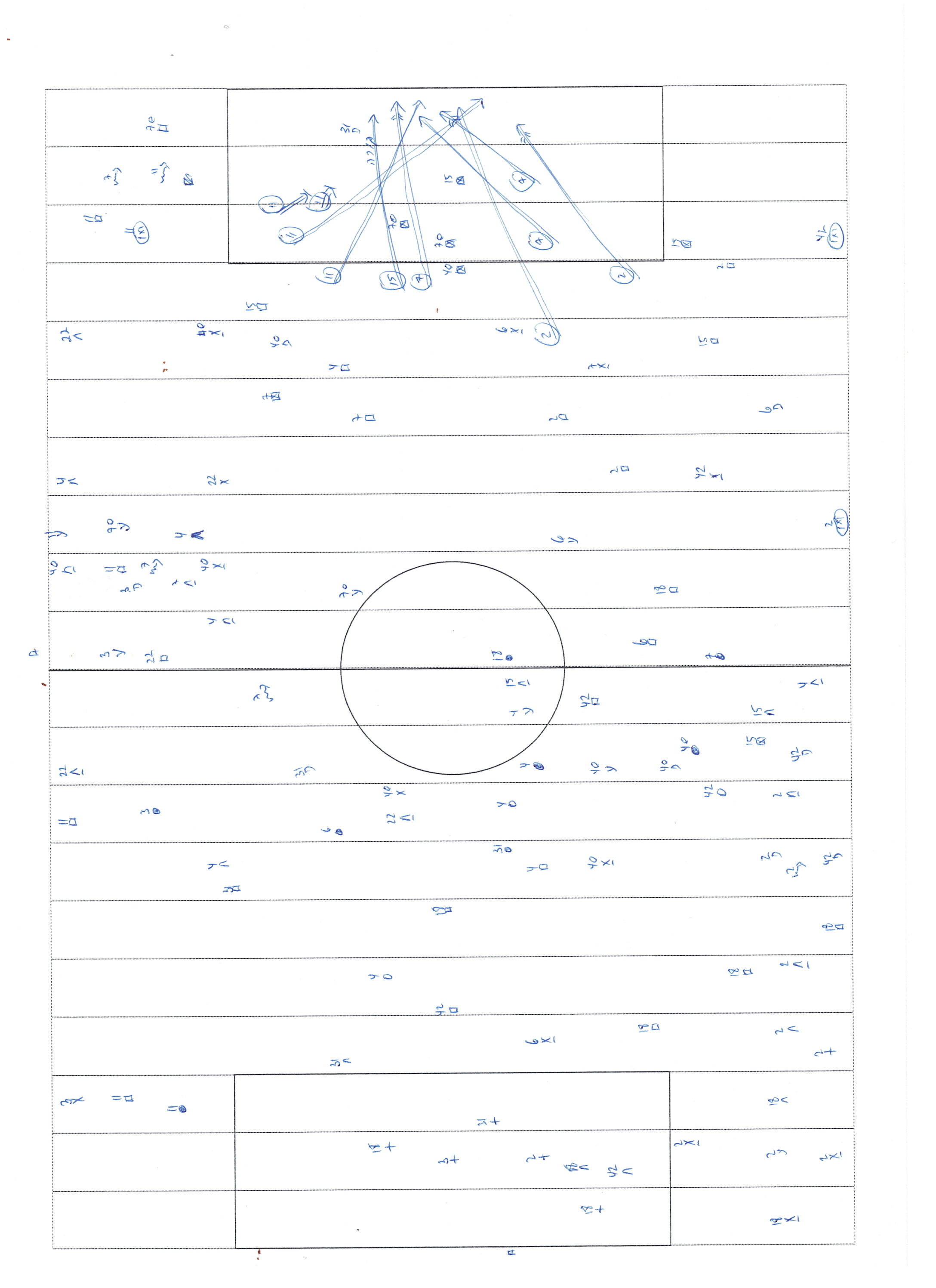

Similar maps, I thought, could be drawn about the movements of the players in football matches, revealing various patterns, like from where your team tends to create its chances, or where they tend to lose the ball over and over again. Aided by the maps, Israeli football supporters like myself, who until then had only local tabloid-style sport coverage, would be able to ask themselves concrete tactical questions and better understand what was really happening on the field. Doing so, I figured, might even help prevent a few arsons and bus-stoning incidents every season. A few weeks later I found myself at Dan’s house, watching a match between Maccabi Tel Aviv and Maccabi Haifa, armed with miniature field maps and a four-colored pen.

One of the first things I learned from these football maps (which over time became a semi-successful blog analyzing Israeli football, run by Dan, myself, and later also Aya, a criminal lawyer who is passionate about collecting Israeli football statistics in her spare time) was that in contrast to the inclination of every red-blooded football fan, I actually love and enjoy watching defensive teams. Studying the first maps Dan and I made, I was surprised at the beauty and cleanness of maps created by an effective defensive team in a winning match—a few long lines (quick counterattacks), and then a dense and narrow assemblage of dots (tackles and headers), the whole resembling a minimalist abstract painting, so different from the Pollock-like scattered mess of short lines and dots made by a high-pressing, attacking team.

While rewatching play-by-plays with Dan—a hardworking defensive midfielder himself, who spent most of his career in bottom-league defensive teams—I realized we were both actually more interested in the “dead” moments of play, in which a defending team doesn’t hold the ball and is only reacting to the movements of the attacking team. The most fascinating moments to me involved teams defending over an extended period as a tight group: an exact choreography veering left and right as one organism, according to where the opposition held the ball. I found these moments—where individual talent bowed its head before the needs of the team, and the game ceased to relate to the spectators and their need for spectacle—magical. Defending footballers are totally absorbed in the moment, in coordinated movement, in the desire to achieve the result—to concede no goal—at any cost.

This discovery totally altered my viewing habits, even when I wasn’t watching for reasons of amateur cartography. Now high-level games in which the same team scored more than two goals ceased to interest me and were impatiently banished from the screen. To my astonishment, by the end of our first season of mapping, it dawned on me that my favorite manager was Haim Silvas of lowly Hapoel Ra’anana. The stubborn club had an average of just 360 spectators per game and had surprisingly clawed its way to sixth place thanks to a highly organized and disciplined counterattacking system, scoring only half the goals Maccabi did in the regular season.

During the recent football off-season I was happy to discover that a new book by Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgård deals directly with the love of defensive football and its connection with literature. The book, Home and Away: Writing the Beautiful Game, is comprised of a long, fascinating exchange of letters between Knausgård and the Swedish author Fredrik Ekelund that took place during the last World Cup in Brazil.

While Ekelund, who attended the 2014 World Cup in Rio, supports Brazil and thinks that the point of the game is “to score goals and do beautiful things with the ball, exhibit control with feet as though they were hands,” Knausgård, watching the games from his home in rural Sweden, is a sworn supporter of both Argentina and Italy, two of the most cynically defensive teams in world football. He loves them because they “played on their opponents’ weaknesses rather than their own strengths. . . . [T]hey possess extreme qualities, but there is something about their never using them in an excessive manner, about never doing anything beautiful for the sake of beauty, only if there is some outcome. And the fact that they can do so, but hold back . . . appeals to something deep inside me.”

The something that draws Knausgård to love defensive football is, he claims, his Protestant upbringing. “I am a Protestant deep into my bones,” he writes of his distaste for the Brazilian team, pioneers of open, happy, juggling football. “I am the kind to deny myself things, to tell myself no.” Brazil, he adds, recoiling somewhat, symbolizes to him vibrant life, life experienced in full. Argentina and its football, on the other hand, are the polar opposite. In one of the letters in the book, he mentions that the original title of My Struggle, his epic series of autobiographical novels, was Argentina.

It’s not surprising that the author of such an ultrarealist series—in which a central theme is the attempt to save everyday life from the clutches of tedium, routine, and death—would be a sworn football fan. After all, it’s the most realistic sport there is. Unlike, say, basketball and tennis, which offer their spoiled clientele an artificial peak every few moments (a basket, a point), football has no breaks. The fan must contemplate a game that goes on and on while most of the time nothing happens. Just like real life.

But Knausgård, again, also has a positive, aesthetic argument in favor of defensive football. The cynicism of the Italian game, he claims, contains a different kind of beauty and elegance. A defensive victory is more nonchalant because it is achieved with fewer attacking players and so is necessarily both more efficient and less tiring. When I read his letters on this topic, I was reminded of a match between Roma and Atalanta, which I saw from the stands on a trip to Italy a few years ago. The game unfolded in a very Italian way, with each team sallying a slow, organized offensive in turn, at the end of which the players would go back to their own half, nobly vacating the space for the opposition’s attempted attack, as in a fencing duel between two honorable, aging aristocrats. Not being Protestant myself, I actually find something Zen-like in the style of defensive football: contemplating and not acting. It’s a style in which you try to appropriate for your own benefit, at the right moment and by the most effective means, the force wielded upon you by an aggressive, cocky opponent, some Barcelona or Bayern Munich, that is occupying your half of the pitch, refusing to leave.

Fascinating as Knausgård and Ekelund’s book certainly is, its conversation focuses only on the World Cup and international football, thus completely omitting one important, urgent element in the life of every football fan: club football. In internationals, maybe because of the low turnover of managers or because of “national characteristics,” teams’ styles hardly change over the course of years, and a fan can choose or gently adjust to a team whose playing style fits the way he lives his life. Utterly different is the world of club football, in which managers and styles change almost every year, and a defensive football lover like me can be caught in a dilemma if the team he’s loved since childhood suddenly begins to play a style completely contrary to his character and way of life. Sadly, this is what happened to me this year, when Jordi Cruyff, son of the legendary Dutch player and coach Johan Cruyff, was appointed manager of Maccabi.

Cruyff Sr.’s autobiography, My Turn: A Life of Total Football, was published in 2016, several months after his death from lung cancer. Cruyff is considered the inventor of “total football,” a highly exciting, attacking form of the game in which the team spends most of the game deep in the opponent’s half. He applied this style first at Ajax Amsterdam as a player, and later at Barcelona as a coach. His son, Jordi, grew up in the youth academies of these two clubs. Both specialize, to this day, in an attacking, no-holds-barred game.

Out of respect for the new manager, and to avoid condemning him prematurely, I recently purchased the elder Cruyff’s autobiography and started reading it. Unfortunately, I abandoned the book after a long paragraph on page 89 in which Cruyff explains why, in his opinion, the most important thing in football is not victory, but entertaining the crowd.

When the first reports of Cruyff’s son’s expected appointment as the team’s coach emerged, I remembered all the wonderful defensive performances I’d enjoyed from Maccabi in the last few years: a squeaky victory over title rivals Hapoel Be’er Sheva, orchestrated by the gruff Serbian coach Slaviša Jokanović; a heroic victory with ten men defending in the derby, led by coach Paulo Sousa. And, of course, the pièce de résistance: an unforgettable away draw at FC Basel, in which Maccabi left its own half only twice the entire game and scored two goals, clinching an unlikely spot at the greatest stage of world club football, the European Champions League.

Concerned, I got on the phone with Dan. Since our first meeting in that French class, he’s retired from active play and now lives in Germany, working as an analyst for Dynamo Dresden.

Dan tried to calm me down. “Do you still hold your father’s opinions about literature?” he asked. My father, Menahem Portugali, published three ridiculous Mossad thrillers in his day. “I’m by no means sure that Jordi Cruyff adopted his father’s footballing philosophy to the letter,” he added.

“But in any case, it’ll be fine, don’t worry,” he said. “Just remember that when a team attacks with a lot of players, at the end of the day, it’s only to keep its opponent away from the goal.”

Editor’s note: Cruyff was replaced after his first season as coach at Maccabi Tel Aviv. The club’s new coach, Vladimir Ivic, used to work under Portugal’s Fernando Santos, who led his team to win the 2016 Euro championship after ending every group-stage match with a draw.