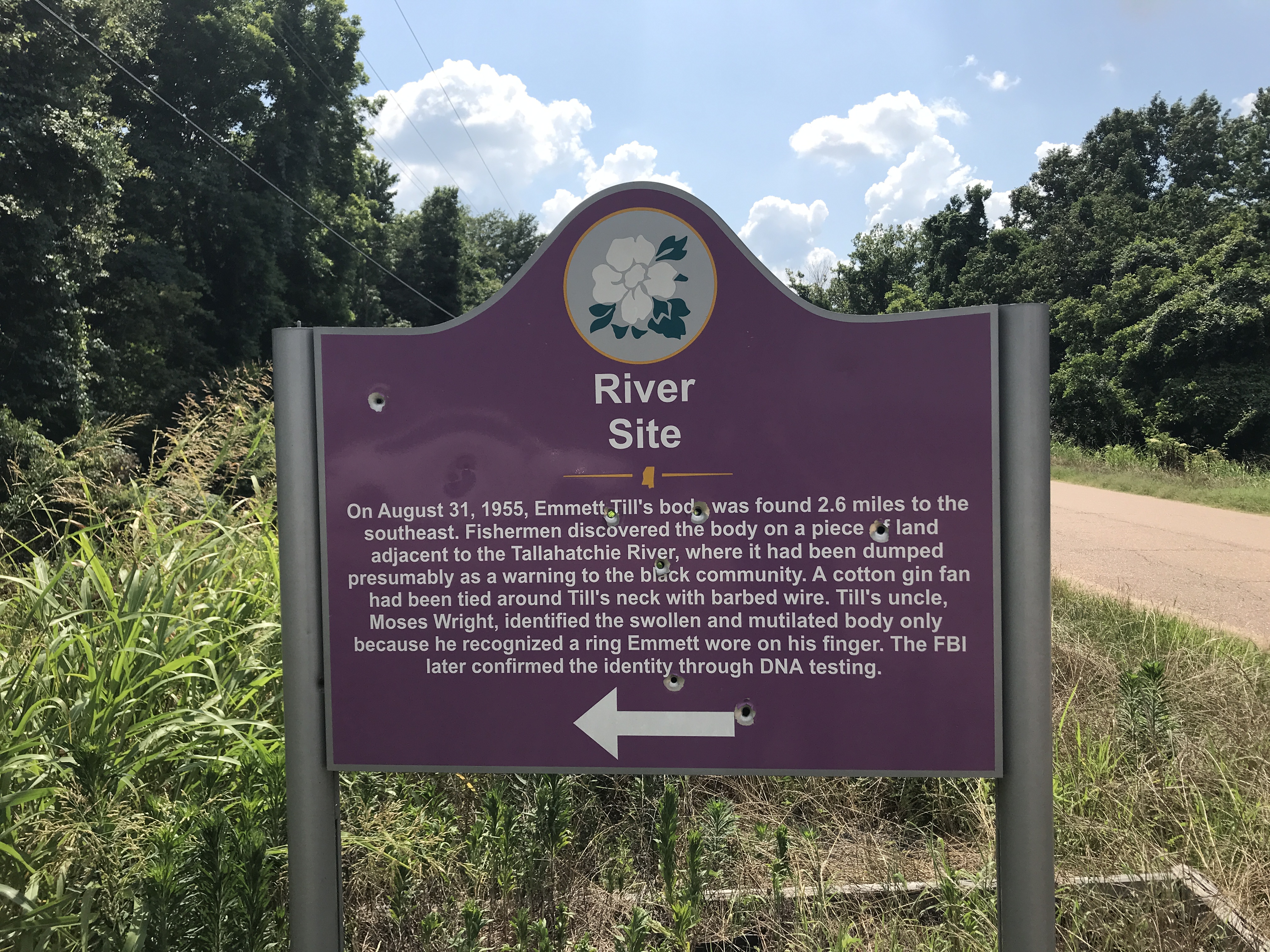

The first sign, pointing us off the asphalt and down the dirt road, is riddled with bullet holes. We knew to expect this, but it’s still shocking. A spray of perforations, haphazard and angry. One took out the last letter in body. One hit just above the a in black. One pierced right between the first and last names, severing Emmett from Till.

This is where it ended, somewhere near here on unincorporated land in Tallahatchie County, a few miles north of the village of Glendora, Mississippi. Where they swaddled the corpse in barbed wire; where they weighed it with a cotton-gin fan and tossed it in the muddy Tallahatchie River; and where it somehow failed to sink, instead emerging riverside where a fisherman noticed it before it got far downstream. The signage—white text on bright purple, placed by a small non-profit—calls this location, gently, the River Site.

The specific place is down the dirt road a couple of miles, flat brown fields to the left, a band of vegetation to the right that follows as the river meanders. There is no one around, except the driver of a big white truck without its trailer that has pulled onto the dirt road behind us and is moving at considerable speed, ominously lurching into the rear-view as we clatter ahead. It’s afternoon, mid-June, clear sky, very hot. We round a bend, the truck disappears, then it’s behind us again, insistent. Tension. Bad things have happened here. We spot the second sign, pull onto the gravel. The truck passes, churning dust.

***

The story is well known. Roy Bryant and his half-brother J. W. Milam killed Emmett Till on August 28, 1955, a few weeks past his fourteenth birthday. Their trial the next month for abduction and murder, before a jury of white men in Tallahatchie County court, saw them swiftly acquitted. Then they sold their story to Look magazine, brazenly owning up to the murder, which they had never hidden. Till’s open-casket funeral in Chicago, meanwhile, gave fuel to the righteous anger of the Civil Rights Movement. Milam died in 1980, Bryant in 1994.

This history is established, but that does not make it settled.

This month, news broke that the U.S. Department of Justice recently reopened its investigation of the Till case, on the strength of “new information.” An official confirmed to the Associated Press that this had to do with The Blood of Emmett Till, a book by Duke University historian Timothy Tyson that appeared in 2017. Tyson’s book made news for its revelation that Carolyn Bryant—Bryant’s twenty-one-year-old wife in 1955, who later divorced and remarried and is now Carolyn Bryant Donham, living in North Carolina—had finally, in her interview with the author, recanted her testimony. Till had never said “How about a date, baby?” as she worked the register in Bryant’s Grocery in Money, Mississippi. He never put his hands on her. “That part’s not true,” she told Tyson, the only researcher to have interviewed her, in 2007. She added, “Nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him.”

Carolyn Bryant gave false testimony twice—at the trial, and in 2004, when the Justice Department reopened the case a first time. (That is when Till’s body was exhumed and autopsied, and his original casket set aside; it is now in the National Museum of African American History and Culture.) The federal statute of limitations on perjury is five years, however, so she is likely in the clear. Still, there are plenty of threads for investigators to pursue, based on her or other people’s information. Other men than Bryant and Milam are known to have been involved in their crimes. Some were Black, present under duress. Where the Justice Department under Jeff Sessions takes its investigation—a fresh stab at justice, a race-relations sideshow, something weirder—is, for now, speculation.

***

The River Site holds its own truth. It’s a short walk to the water, a hundred yards or so, the path traversing some low bramble on the way to the tree-shaded riverbank. Sunlight filters through and mottles the dark alluvial soil. The river is only a shade less brown. The Tallahatchie is wider here than at some other points; the current is slow. There is a little notch in the dirt that offers an easy step down to the water. You feel drawn to stand right there. Aside from the bugs, there is quiet. This must be the place.

None of this is over. Not Emmett Till; not anyone else. Driving in, at the edge of Glendora, we had passed a marker in remembrance of Clinton Melton, an “outspoken black man” killed in late 1955 by Elmer Kimball, a friend of J.W. Milam, “allegedly over a dispute about filling up a gas tank.” The signs honors Melton, but the text tells of still more tragedy. It reads: “On the day before Kimball’s trial in Sumner, Melton’s widow, Beulah, was apparently forced off the road near Glendora and drowned in Black Bayou, leaving five children orphaned. Kimball was aquitted [sic] of Clinton Melton’s murder.”

Established, not settled. History is restless. Afterlives are busy. Every record is incomplete. Many records are absent. Most records. The archive is mostly omission.

The riverbank is quietly magnetic. It aches to step away, but we follow the path back to the roadside. The purple-and-white sign here, with its sober text noting the significance of the spot, is pristine. No bullet holes. The vandals were too lazy to come down the dirt road, we joke, but that isn’t true: This sign is brand new, a crowd-funded replacement for one even more violently desecrated.

I notice a small camera keeping watch, mounted on a tree.

There is a rumble. The white truck is back from wherever it went, now hauling a trailer. I stand by the dirt road, setting up for eye contact. The driver is a Black man. I wave in greeting; he gives me a big wave back, and carries on.

Before long, we follow. Our rental car has Mississippi plates, which indicate the county of registration; ours comes from Forrest County, which bears the name—it suddenly dawns on me—of Nathan Bedford Forrest, the Confederate general and early Ku Klux Klan leader. For now, I shove away this unpleasant realization. Sufficient unto the day.

***

Postscript: One week after this article’s publication, the sign at the River Site was again shot up.