“When describing a person of colour, try not to use food words. No chocolate, nor caramel, no goddamn espresso,” as Ellah Wakatama Allfrey, the Zimbabwean editor and literary critic, once put it. “Your writing will be better.”

It’s an argument that’s been made many times, but something about how she drew the lesson out with options… the crisp goddamn stuck in my mind. There’s no compromise in the words try not to. She is saying About goddamn time this black-skin / food-colour palette was done with. Don’t you dare use diminutive contrasts of whole human beings with… butterscotch, burnt sugar, cinnamon, roasted almond, mocha, Green & Black’s velvet edition 70% cocoa. No matter how euphonious the transits of words between mouth and brain, brain and pen; no matter how high-minded the intention, how aesthetically pleasing the food, how stretched your astuteness in search of just the right literary adjective to capture Nyakin Gatwech’s shade of black.

I agree with her in principle. The comparisons are embarrassing square pegs in hexagonal holes. You can’t say them without feeling… well… contrived. You say the words and skip quickly away, escaping by the skin of your teeth, with sheepish pauses and overcompensating enthusiasm. Still, some people don’t worry at all. They jump in with two feet, with a whimsical swagger. I envy them; perhaps we must give them credit for getting it over and done with. Not overthinking things in a no-win situation.

Allfrey doesn’t live in Somerset West, in Western Cape, where the sun doesn’t rise, but rather luxuriates like a fat monarch rolling around in his bed, surrounded by a carousel of mountains and valleys. If she did, I wonder if she might concede that colour-like food platitudes are by thousands of kilometers the lesser evil.

Somerset West is a remarkable, old-fashioned toy rotating around a point of light, harnessing sunlight through cutouts in the walls of the city, through clouds and Helderberg Mountain, through unpredictable weather patterns and micro ecosystems placed where God wishes. Colour, stunning idiosyncratic expositions of colour, is the theme of every single day: Colour on spectacular parade: Colour the obstinate subject matter: The undercurrent: The problematic.

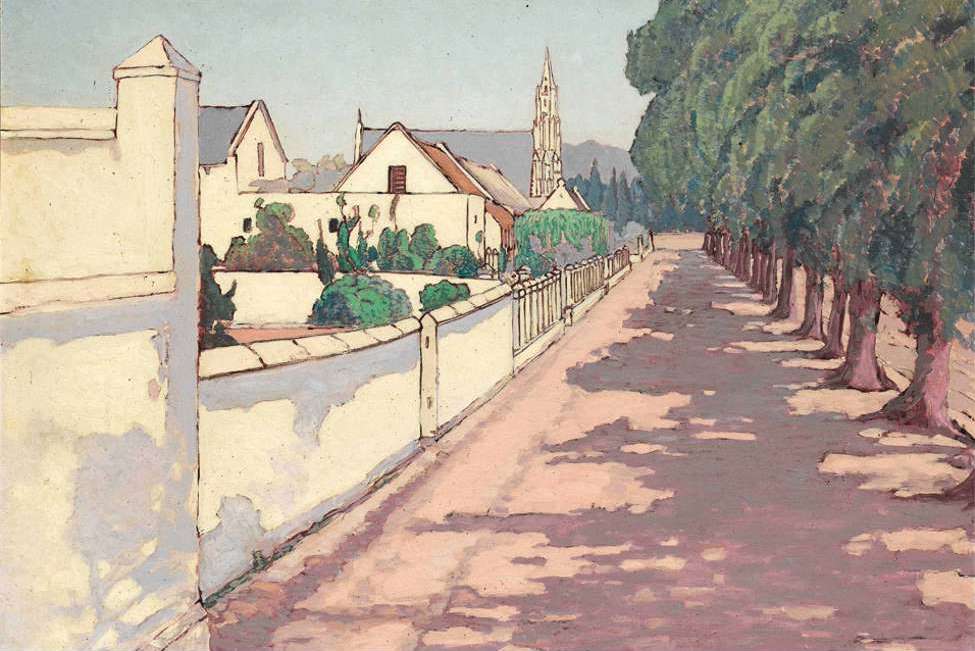

If we successfully turn our attention away from the gratuitously unscripted swathes everywhere, from the ceilings of lilac and chocolate peaks, spun-sugar clouds spilling out of sky container, pastel houses walking up mountains, from brandeis, electric, periwinkle, blue, sky tones sovereign over descriptive words, spring embankments of lime, purple, fuschia, newborn blooms rising out of valleys of drab streets… If we turn our backs on the moon that comes out at 2:00 pm in the midst of downy clouds, like an LED streetlight that forgot to switch itself off, if we disregard dusk cerise fires without appointment submerging the heavens above: The Jacaranda swaying and raining rugs of blossoms in street-niches for improvised love-making… If we shrug off the sulk of towering blue-gums keeping watch over the suburbs with the full-fat ominousness of mafia lords living in the arteries and mood of an occupied boulevard…

We can’t avoid the temper of colour on people, in people. On terra-firma, in moving cars, when talking about flesh and hot blood, things are complicated. Painful. Chocolate, coffee, and butterscotch are evocative safety nets when depicting Black, White, Coloured. And so, rather be ridiculous than racist is what I cautiously propose. The solid serious words are the problematic parameters. They offer no cushion, no coy compromise in addressing black skin. Any skin. Because it is never just skin. There is no safety from the invested bigotries in black and white. I don’t know; maybe Allfrey’s annoyance may have to be contextual, and not in the context of here. Because colour is every goddamn place here and the goddamn exasperation is not goddamn caramel or espresso or chocolate.

One day I wandered the aisles of Woolies looking for laundry soap. I beg your pardon: In other parts of the world that I have lived in, I have been well within my shortcomings, my splitting head, my sensory sensitivities, my inability to deal with too many visual details at one time to be confused by all the brands and formulae and unique functionalities of washing detergents. It isn’t the first time that I have had to step up and ask a man/woman in uniform in a shop:

I need laundry soap for coloureds.

Where is the detergent for whites please?

I shouldn’t have expected that this man would conclude that I was talking about coloured people. In other parts of the world he would be sure I meant clothes, and that my intention was nothing more than the necessary finickiness required in determining the best separate care for all the categories of clothing in my house. He would be sure I wasn’t attempting to be stupid nor rude nor racist. Yet I said the words in Somerset West one afternoon in the supermarket: I asked for detergents for coloureds standing opposite a man with unsuccessfully veiled incredulousness in his face. I said the words and then only after noticed he was a mix of white and black—Coloured.

People use the word coloured in Western Cape, without missing a beat, to mean mixed race. They mean that black plus white gives colour, I suppose; but we can’t say coloured almost anywhere else in the English-speaking world without being looked over with horror. Cafe au lait immediately feels more prudent to describe this man, doesn’t it? But I’m not talking about political correctness here. I’m talking about context and grace, and the ability to touch another human being without having them recoil. (Thank God for food and its comforting moisturising quality in relationships.) Because nothing could have been worse than what I said that day. Not coffee plus half-fat cream with butter and cinnamon. Not chocolate clothes, a pair of trousers mocha like my skin . . .

Would the man not have just thought me eccentric, silly, high, “special,” heavy handed in my expressions? Heavy as dark double espresso.

I wouldn’t have said coloureds, then begun to hyperventilate with embarrassment and stress. What I mean is … But it was too late.

So if we cannot discuss human beings in comparatively innocuous chocolate and black vanilla, in blackberries and milky tea, cafe au lait, pink as roast beef, ruddy as strawberries… if one cannot walk into a shop in the Western Cape and ask for soap without risking a racial gaffe when using the words black, white, coloured, then for goodness sake what are we to do with ourselves? Black and white are old deep wells of meaning with lurking bad things in unexpected crevices… mined tracts, as was brought home by stepping into the shoes of my Afrikaner friend, C, or, shall we say, riding in her car one morning.

One autumn morning on Reunion Drive, when gentian-violet clouds scurried along glossy grey pavements, the spattering of cold rain following quickly, C and I sat in the car, inhaling beauty, exhaling lukewarm words. The car moved slower than the people trekking through the street. We watched the heavy motion of shoulders tucked in against rain and grey darkness, laboriously ascending one hill, then another, and then another. I was mesmerised by the bodies of walking women, the smooth-talking gyration that fatigues the eye because of the effort suggested in every step, because of all the parts moving at the same time—bodies that would have done well to adapt to climbing and descending innumerable elevations by being leaner. Why carry so many strenuously revolving spheres? What does it do to the heart? C cut through my thoughts, through the compressed air in the car, with a notion that she assured me was scientific.

She said people like me—melanated people, people of colour, Xhosa, Zulu, Venda, Ndebele, etc.—don’t have peripheral vision.

She must have been able to read on my face the questioning, the confusion. Peripheral vision? Black people don’t have peripheral vision? What do you mean?

Her words and mine, our breaths had clouded the windscreen and windows until we could barely see out of them. She wiped a circle of vision with a closed palm. In the pause, I filled in the gap… Amasi-drinkers. That is what she meant. “That”… the cushion to protect this lady, the skin intuitively moving back over my claws and fangs. “Amasi drinkers,” I said, otherwise I risked menacing her. I could have chosen other words. She would have imagined me angry when I was not. I might just have been slightly irritated, unnerved, vaguely repulsed? I cannot now put my hand on the feeling as I could not on that day. I realise that the reason is that feelings cannot be trusted. And she would never have aired another stupid notion if I responded with what I felt. What is friendship without stupid notions, crazy ones? Without the overlooked gaffe between two people, the dirty nose and stinky breath? I wanted her to air the fluff so that we could wipe it away like she wiped the windscreen with her closed palm. And I wanted to be safe to be idiotic and be forgiven, and be corrected. Stand corrected, not grovel-corrected.

“Can’t see out of the sides of their eyes”, she clarified. It is proven, and some Afrikaner scientist wrote a paper on it… and this explains why they/we/us/me are always walking in the middle of the road and getting in the way of moving cars. I wanted to say that perhaps we were always getting in the way of moving cars because we were walking and not in cars. That the average black person/Amasi drinker in Somerset West is a pedestrian and has no car. A pedestrian who must walk every day understands certain necessities the woman behind the wheel does not: That she must enforce her weight, her rev and step and sentience over that of a motored engine. Her pre-eminent right to occupy space over that of an inanimate object, regardless of mapped roads and highways and laws giving these entities precedence over people. The best drivers get overpowered by their cars—find themselves being driven rather than driving, bullying walking people and honking them aggressively out of the way. The pedestrian in defiance rolls in the middle of the road to enforce the higher law. I suppose that is why adaptation of these women’s bodies never took place, will never take place—because people cannot be trusted with remembering that other people are the most sacred items in the world. We must be constantly, laboriously… in indelible rolling cogs of flesh… retold. I was introduced to many generalisations when in Somerset West; introduced to the sour milk called Amasi that black people—“only black people”—like to drink. The introduction was accompanied by a facial expression that said more than the words. Not every generalisation can be thrown out of a moving car. Some are a way of saying: Look, this is what is cultural here. This is what happens, full-stop. Black people like their Amasi. White people don’t like Amasi. Or… rarely will you find the white person who likes Amasi. In Venda Limpopo, a woman must lie on one side to greet her husband in the morning and cannot get up until he says so, until he grants her permission to rise. These are cultural facts. These are accurate generalisations.

I rolled my passenger seat window down one inch. An inch and a half. I looked at C for a long time, laughed wearily and looked away. If I had worked harder at teenage recklessness, I could have easily given birth to this lady and she could be my daughter. I couldn’t berate her. I advised her not to mention the notion, the science nor the scientist, to anyone else melanated, Amasi-drinking, Xhosa-speaking, walking-in-the-middle-of-the-road- like-revolving-spheres person that looks like me. We moved on. We had progressed without fisticuffs. Traffic moved. We successfully drove past the obscenity, claws retracted silently, past the bright-coloured fatuous Afrikaner theory, an incendiary device thrown in a small car on a cold morning about black people and white people with fish eyes. We were both intact, C and me. I knew her well enough to appreciate the closeness she felt towards me that made her bring up something so ridiculous, so unspeakable. If Amasi-drinker is what it took to keep the darkening clouds from filling the space of the car and drowning us, then I agreed to drink Amasi. I will never forget that I stood opposite a man at Woolworths supermarket asking for detergents for coloureds… needing grace. Feeling lower than foolish.

I arrived in Somerset West in the first quarter of the year when adult colouring books were becoming a global phenomenon. They were avant-garde medication for adult anxiety. Mindfully filling in flowers, mandalas, and paisleys with crayons lowered blood pressure and calmed the mind; simple pleasures for adults. I had moved all my things from Nigeria where we have a very small pack of crayons, to the New South Africa. The New South Africa that had successfully dealt with Apartheid, and was on its third Amasi-drinking president, and had sent Amasi drinkers (alongside Brai-ers, South African lovers of the Brai, the lovingly barbecued meat; the Afrikaner) to us in Nigeria to man South African enterprises like Multichoice, MTN, Standard Bank, and yes, Shoprite. That same Shoprite in Lekki Peninsula phase 1 where I had stood one evening, before my move, watching a Nigerian threaten to beat-the-hell out of an Afrikaner who had cheeked him. The shock of the threat had made the Brai-er remain in the crowded supermarket, his doused eyes darting nervously, unsure now about going outside the doors where the Nigerian would surely be awaiting him. This Brai-er should have asked about Nigerians. Those people who never beat you without making the experience unforgettable—beating something out of you, whether it is hell, glory, or nonsense. The threat of a Nigerian-beating must always include details of which ingredient will come forth with the application of violence to person.

It was almost certain that he was a new arrival in Nigeria from a not-so-new South Africa. He and his behaviour were the truth, and all the other bullshit propaganda about the end of Apartheid and Brai-ers regarding Amasi drinkers as equals had not become integrated with his new Nigerian residency and public personality. Dangerously uninitiated, he had cheeked the wrong kind, the Nigerian wearing gang colours waiting for a stray spark: “No foreigner comes into my country and gives me shit unless I let him… Unless I let him do you understand me?”

The man he had offended was a big strapping bald-headed Nigerian. His head glistened in the supermarket lights all the way down from the high ceilings of the checkout points. How was this man in any way or form mistakable for the shrinking South African Amasi-drinker. Every pore on him exuded impatience. His car was parked outside the supermarket. His bonnet was still steaming from driving in the heat of the day. He was dressed for work alongside his donning of the time-honored birthright of confidence gained without interference of white men. He had probably met less than thirty white men in his whole life. Most of them were European and urbane, with dog-eared Bradt Travel Guides on Nigeria under their pillows chooking their heads as they slept. Most of us in the supermarket that day shrugged and looked away from the soft spoken fracas that graduated into the openly delivered threat. If I could read minds, I would say we wished the man hadn’t wisened up so quickly, had instead sauntered outside the supermarket into the cooling evening where the Nigerian would have delivered on his promise and beaten-the-hell, heaven, and glory out-of-him. There the bruising and bursting of sun-cooked Bria-er that did not take strong cognisance of the nature of the people among whom it was living would clear the air like a blood sacrifice made for guilt. The man would never look at another Amasi-drinker the same way again. In our Nigerian box of crayons there were two colors: foreigner (oyinbo) and Nigerian, crayons that have nothing to do with shades and hues and everything to do with knowing your place among strong-willed people. The foreigner had better know his place in the Nigerian box of crayons. He’d better understand that a man does not earn automatic deference by virtue of being white.

I had taken everything that meant anything to me and moved from Lagos with its flat landscapes to Somerset West with its mountains and valleys, where Amasi-drinkers—people who look like me—stand with their backs to the wall of a Somerset gas station in winter, waiting for their cylinders to be refilled. There was a scarcity of gas that year. I walked in and wondered why people had their backs pressed against the windows of the front wall, bodies slouched, eyes lowered to the floor. A large woman with long beetroot hair stood behind a tattered counter with one enormous jar of marshmallows covered with pink sprinkles. She smiled often, good-naturedly. Another elderly woman was answering a phone call in the background, her tone of voice suggested she was in charge of the station. I entered the narrow passage between the counter and the wall of bodies curtaining the weak sunlight coming in through the windows. Me, the Nigerian woman with two pencil colours in her box of crayons stepped forward and raised her voice. It was said all the time in the Western Cape that Nigerians were pushy, arrogant, annoying, loud, in your face. We grated on the nerves of South Africans, but it got us respect didn’t it? It got us the same quality of customer service that the Brai-er believed was his entitlement. Or in the wrong place at the wrong time, it got you cut up with a machete. In Mitchell’s Plain or Philippi. Shot in the face in Bishop Lavis. Set on fire in Kayelitcha. You were like a mirror image that enraged the looker. Uppity arrogant Nigerian who thinks himself too good to drink Amasi. Take that! An Amasi drinker that looked like you tore into you, and the shock killed you before the contact of brutality. We are the same aren’t we? Aren’t we. The hatred was confusing, but in the context it made sense. In the gas station it made sense. In a moving car on a black-and-gentian-violet morning, it made a lot of sense. The Brai-er put the phone down and served me, called someone from the back to get my cylinder. It was clear from my voice that I was a foreigner, so her attitude was wiped clean for the foreigner with a nice car. The kind you don’t see Amasi drinkers driving.

Goddamn! I thought.

Brai-ers often commented on how exotic the words coming out of my mouth were. Oh you are that beautiful Nigerian woman. Any accolade they would afford me, as long as I was not a coffee bean rolling down into the grinder on my back—not a South African Amasi-drinker. The rage made full-fat sense.

Why is a coffee-plus-cream safer than black, white in describing people? Because this place, Western Cape is a Konkoksie. Slegte Konkoksie that nobody can hold down. Beautiful country, Slegte Konkoksie. My daughter, who speaks Afrikaans, says the word I need is Erg before Konkoksie. What does it matter?

The plain truth was in the face of every stunning Jacobus Hendrik Pierneef landscape that had no blemish of human being in it. If you saw one person, two, three on a Pierneef canvas, you instinctively began to worry about colour. You hovered and worried and forgot the allure of the landscape. Best to leave bodies out of the paintings altogether. There was no word sufficient to describe the itch of the fabric of the South African colour wahala. We will never belong here. I’m resolved to get my children out of this place with its simmering hatred and discolourations.

Canadians, Germans, the British, South Asians, Ukrainians, Poles… Afrikaans, English, Ndebele, Northern Sotho, Sotho, Swazi, Tsonga, Tswana, Venda, Xhosa, Zulu, Motswanas, Somalians, Zimbabweans, Malawians, etc., etc., etc. are all jumbled together—obstinate peas, too much water, oil floating on the top of everything. The oil, the oomas and oopas drifting serenely past in the latest BMWs, Audis, and Jaguars, past the shadows of settlements and locations where Amasi drinkers live. The ungovernable water overflowing the cooking—the South Africans coming over the border from neighbouring African countries. The Namibian shark-farming Brai-er with a Moroccan wife living on 2 acres in Gordon’s bay; hard working determined Zimbabweans, Malawians ready to do the work the Xhosa take for granted and the Zulu feel is beneath them; the Europeans who keep homes in manicured estates in Somerset West, coming and going for the favourable weather and the bragging rights across the fence to the neighbours in Wimbledon, called Swallows for coming and going in tune with good weather… the black-eyed beans… well…

In Somerset West, a black woman driving a black car attracts stares both good and evil. The Strand on a beautiful day is fastidiously colour-coded; the sand on the beach may be as soft as desiccated coconut, as inviting as churned butter, but forget that and watch the people—they are the real mood of the waterfront. Unlike a Pierneef painting, it is the people you need to see because you have to be careful where you go and how you go. Opposite the water there is a line of quaint shops, Bikini Beach books, a gift store where you can buy a doll for pins. The name written on the doll is mother-in-law. There is an outside sitting area with Brai-ers drinking Rooibos, eating ice-cream. There is an Ocean Basket restaurant with tall glass windows and air-conditioning. A curved line of immaculately polished Mini Coopers parked just before the Strand turns to tall apartment buildings and shops. There is a club that meets on the Strand for Mini Cooper owners—all Bria-ers. Every ingredient, every Brai-er, Amasi-drinker, Cafe au lait take up their places before blue-turquoise waves, keeping to their boundaries in the beige sands. Cafe au lait children on a field trip from school play by the man-made rock pools. Their teachers are coffee and cream, to go with coffee-and-cream children. The teachers pretend they don’t speak Xhosa or understand it, only Afrikaans. The children will learn the expediency of this soon enough.

The same way many of the Brai-ers pretend they are not Afrikaans but British, English, German. Something else from someplace else. The children sparkle in the sun like jade droplets, but we are not allowed to say that. Amasi-drinkers swim the loose currents in their clothes and underwear. Nearby, teams of gangly boys play soccer, their voices cutting through the wind. Coolers are visible from the road, as are giant bottles of orange soda. At the Brai-ers end, things are quiet. Bodies walk, sit, smoke cigarettes, pretending it is Muizenberg. Big-boned women with shrouds of hair, so beautiful, the blue of their eyes lighten or deepen with the shade of mountains, sit and meditate. One elderly Brai-er stands out in his mustard socks pulled past his shins and cap-toe shoes. In his British army officer’s shorts, with a comb for his moustache sticking out of the top of his right sock. His teeth are yellow slabs. The blue of his shirt mirrors the sky. No one, not one, dares wander past their boundaries.

If you don’t learn the roads by colour, you are living dangerously. No matter what the car navigator tells you, never go through Victoria Road right towards the Somerset Mall, through that area called Gardens where the Cafe au lait gangsters live. They will walk in front of your car, pull you down from it, and set you and it on fire. KFCs, Hungry Lions, and Nandos are mainly for Amasi-drinkers because they like their fried chicken. Black arums—“black stars”—grow wild on the banks of the N2 highway where Brai-er police officers have recently been ambushed and murdered by Amasi drinkers. Whatever happens never stop your car and get out of it on the N2. No matter what shade or hue you are. It is hot and beautiful and serene on the ground; up on the mountains fires spread and burn treacherously, chasing down and swallowing homes and vineyards. Brai-ers live on the mountains. When they and their possessions burn, Amasi drinkers think of the slow justice of God and its brisk merciless descent.

I would say in answer to the rule about skin-color and food: let us eschew the metaphors. Coconut, sugarcane, curry, pawpaw… most especially rounded fruits. The “like” between person and food is obligatory humility. Never move it. Never discard it.

But I feel inadequate to make rules. I want to talk about Julita who I met in the kitchen shop in the Vergelegen Mall. I don’t believe she would mind if I said she had peaches-and-cream complexion. She did. And she had an accent. It might have been Polish or Russian. I’m not sure. The same way I’m not sure how we started to discuss Egyptian ducks and their audacity in the Western Cape, and how Christmas was approaching and why couldn’t one just jump on one of these ducks and roast it whole and stuffed. She had just moved to Somerset West with her Afrikaner husband. They were desperate to buy a house. From ducks, we started to talk about what Nigerians would do, would eat. We laughed a lot. She said where she came from it was the same:

Guinea fowls wouldn’t come and wake you up in the morning because you would make them disappear, and all kinds of lovely aromas would afterwards come from their frying in the kitchen. I mentioned Amasi. She said she loved Amasi, or a type of it. Back home they made it into cheese and spread it with apricot jam. She had a recipe would I like it?

Get a jar of Amasi milk and pour it into a pan. Heat it up slow and gentle until it ends up like scramble eggs or curds. Let it cool, then scoop it into a muslin cloth. Tie the ends of the cloth up and hang it on the neck of the sink overnight to drain the water from the cheese. In the morning, scoop your Amasi cheese into a boiled, glass jar and store in the refrigerator. Spread on sourdough bread with good quality apricot jam.

The problem with conclusions are that they inevitably take flight, like those Egyptian ducks I swore I would show my Nigerian side one day with a knife, Cameroonian pepper, and a large roasting tray. They shift skillfully as you hover, preparing to pounce. I had again packed my bags—everything I had brought to Somerset West was ready to move continents this time. The professional movers were coming to put them on a ship. South Africa had taught me some things in three years I had never experienced in four decades. I had never seen drought in 42 years, then I lived through three years of it. The night Zuma stepped down as president, it rained so wholeheartedly, you knew without doubt the worth of liquid gold pouring down from the sky. I had woken up to views of the most beautiful mornings over the most magnificent landscapes the world will ever own—no clichés, no generalisations. I had learnt to say boerewers like a native. Learnt that kissing teeth might be punctuation in Togo, insignificant in Nigeria, but it is anathema to South Africans.

That Zuma is not black; he is in fact orange.

I had to definitively discard the word “coloured”, not dare let it sneak on the plane with me. Oh, and I learnt that Mitchells Plain—the café au lait suburb named the most violent, crime ridden, feared part of the whole of South Africa, thirty minutes on the N2 from Somerset West—had that Autumn run into Jesus. There were revival services going on. Words of prophecies and unbelievable healings were taking place in a church there, pouring out of doors into the streets. The rumours were that people you wouldn’t walk past with an easy mind on the corner of George were keeping watch over your possessions for you, guarding your cars, helping old ladies cross the street, picking up your money where you dropped it and handing it to you. Those café au laits reprobates with knives up the backs of their jeans, who will cut you without remorse, they were manifesting the kingdom of God. Removing their clothes and unveiling angels. You know how it reads: In that very place where it was said of them ‘You are not my people,’ the café au laits—“them”— are being called the sons of God.