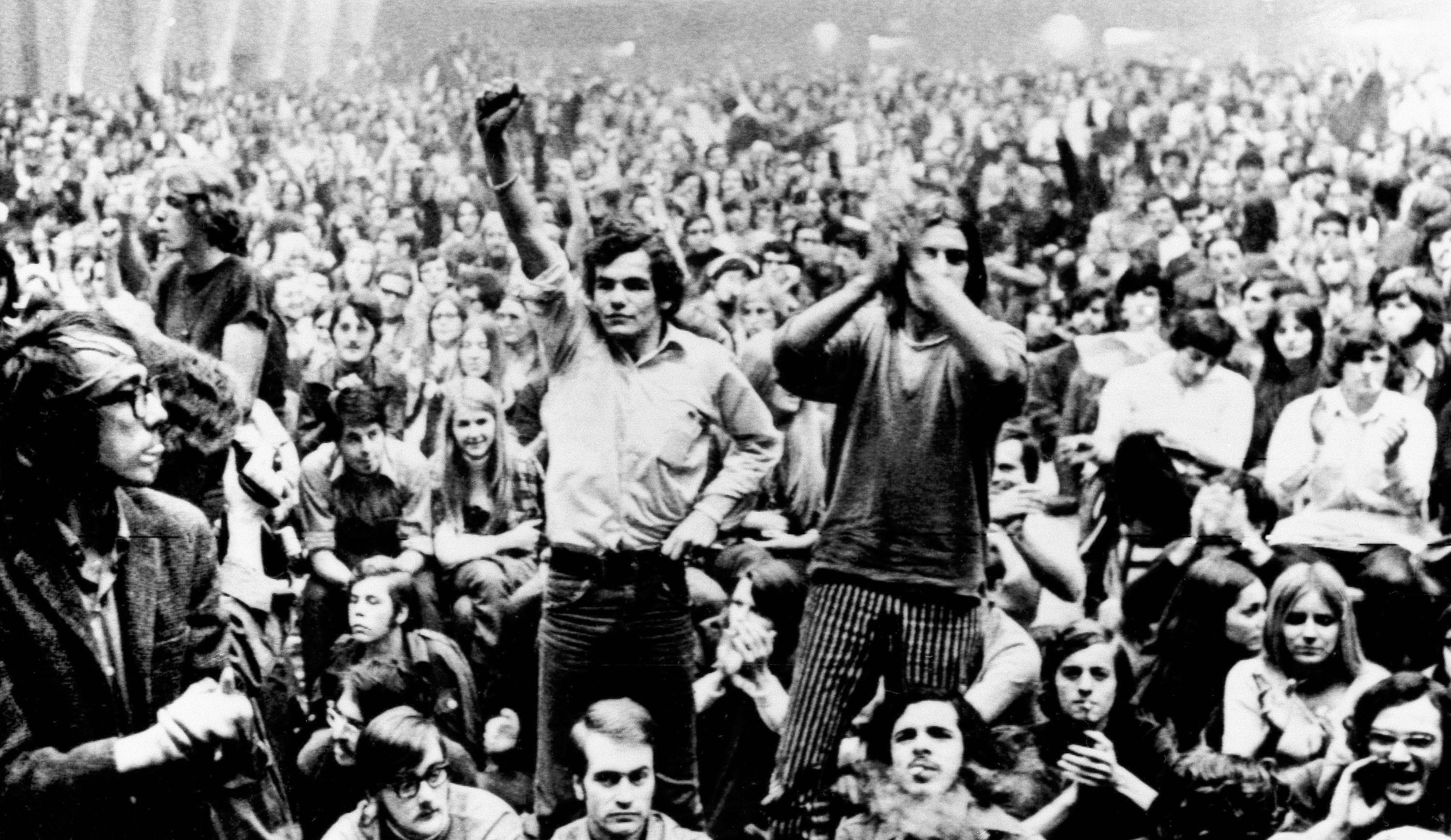

In the 1960s, the separatist group, Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) formed. These French Canadians attempted to connect their cause to that of groups like the PLO and the Black Panthers. During a trip to New York City, FLQ member Pierre Vallières was arrested for associating with the Black Panthers and subsequently jailed at the Manhattan House of Detention for Men.

It was there that he wrote one of Quebec’s most infamous books, White Niggers of America. Part memoir, part revolutionary screed, part Marxist analysis, it found Vallières comparing the Québécois’ social and economic conditions to those of African-Americans in the United States.

It may, then, come as little surprise to many (including former Canadian poet-laureate George Elliot Clarke) that playwright Robert Lepage would create plays like “Slav” and “Kanata,” a distinct echo of the White Niggers moment.

When “Slav” opened at Montreal’s International Jazz Festival on June 26th, 2018, someone should have known what was coming. Robert Lepage, the Canadian playwright, producer, and director, wrote, directed, and produced the show, described on the promotional posters as a “theatrical odyssey based on slave songs.” Though the show uses slave songs and slavery imagery, only two out of seven actors were people of color. The co-creator of the show, Betty Bonifassi, explains the reasoning for this casting: “We don’t talk about black and white in the show. We talk about human pain, experienced together. All cultures and ethnicities suffer the same.”

The ensuing backlash led to the remaining shows being canceled, prompting accusations of censorship and denial of artistic freedom. Lepage was planning another show, “Kanata,” about white/Indigenous relations in Canada. In this case, he hadn’t cast any Indigenous actors, and was depending on video footage of Indigenous people’s testimony. That show has also been canceled. No less than the leader of the Parti Québécois came out to deride the decision: “This step back for artistic liberty is intolerable. The pressures of censors and the moral weakness of co-producers cannot have the last word when it comes to artistic freedom. Debate, yes. Support for more diversity in the arts, absolutely. Rolling back freedoms, never!”

How could Lepage not predict this kind of reception? How could anyone think white Canadians playing the roles of slaves was a good idea?

The entire fiasco becomes less surprising if you consider the ambivalence that many Québécois feel about their history. Quebec has been both a settler colony and a postcolonial population, but these are facts that the Québécois rarely confront. Quebec was conquered and colonized by the British, but it has long denied its role in the colonization of the Indigenous people who were there before them. The Jesuit Relations—mission chronicles written in the 17th century, in New France—helped frame an entire continent’s understanding of the people who were living in Canada before Cabot set foot in New France. These were the opening chapters of Canada’s story of colonization, funded by the Catholic Church, and were written in what would become Quebec. But when Quebec banished the Catholic Church during the 1960s, many felt that Quebec had also absolved itself of other histories: residential schools, forced conversion, oppression, and genocide.

Enter White Niggers of America.

Up until the 1960s and 1970s, the Québécois were poorer and less literate than their Anglophone counterparts, who owned and ran much of the industry and finances in Quebec, despite being a minority of the population. The Québécois, though, were never slaves. There were slaves in New France and Lower Canada, as well as a thriving trade of Native slaves for African Slaves with Louisiana and the French Caribbean. But the Nègres blancs d’Amérique were not the slaves in question; they were the enslavers. As Haitian-Canadian author Dany Laferrière put it in the first version of his novel Chronique de la dérive douce, when the narrator spotted a guy on the metro reading Vallière’s book: “C’est bien, mais faut pas qu’on/oublie qu’il y a aussi des/Nègres noirs en Amérique.” [That’s fine, but we can’t forget that there are also black Negros in America.]

The Quebecois have a habit of erasing this part of their history in the name of claiming solidarity with others, a move which crosses over into cultural insensitivity and outright appropriation. That Vallières’s book is still held up as a classic of Québécois literature—with glowing reviews and reflections appearing every 10 years on its publishing anniversary—helps clarify how people like Lepage and those who defend him can seek the cover of artistic freedom and ignore the accusations of cultural appropriation. Many in Quebec don’t see works like “Slav” as cultural appropriation, but instead as part of a shared heritage of oppression.

Vallières and his book tapped the spirit of the Sixties, articulating a frustration that resonated with many Québécois. The Slav and Kanata incidents demonstrate that the zeitgeist has changed. Vive le Québec libre! can no longer come at the expense of marginalized populations.