You’ll find this image of an elephant being pruned by the Oakland Athletics in Temescal, in the middle of a series of five street paintings that adorn the façade of an otherwise apparently-vacant building, lodged between the East Bay Church of Religious Science and Kelly-Moore Paints.

The former is one of the Centers for Spiritual Living, practitioners of “Science of Mind” which–as I googled to learn–“affirms the Absolute Reality of God, the unity and sacredness of all life, the divinity of the individual being, the inherit wholeness and worth of each person, and the right of each of us to the good of life.”

The latter is a paint store. “Quality Paints in Unlimited Colors.”

It’s actually an odd, ominous painting; who are these faceless spectators in the foreground, in dark silhouette? The building in the background is the Temescal branch of the Oakland Public Library, for some reason. But what is happening in it? Perhaps we seeing a figural representation of a baseball game, with the players allegorically tending their pastoral object? Or perhaps the team has become a rich man’s plaything—a decoration for his garden—with the players left to serve as mere grounds-keeping labor, and the fans shadowy and obscured, forgotten in the foreground.

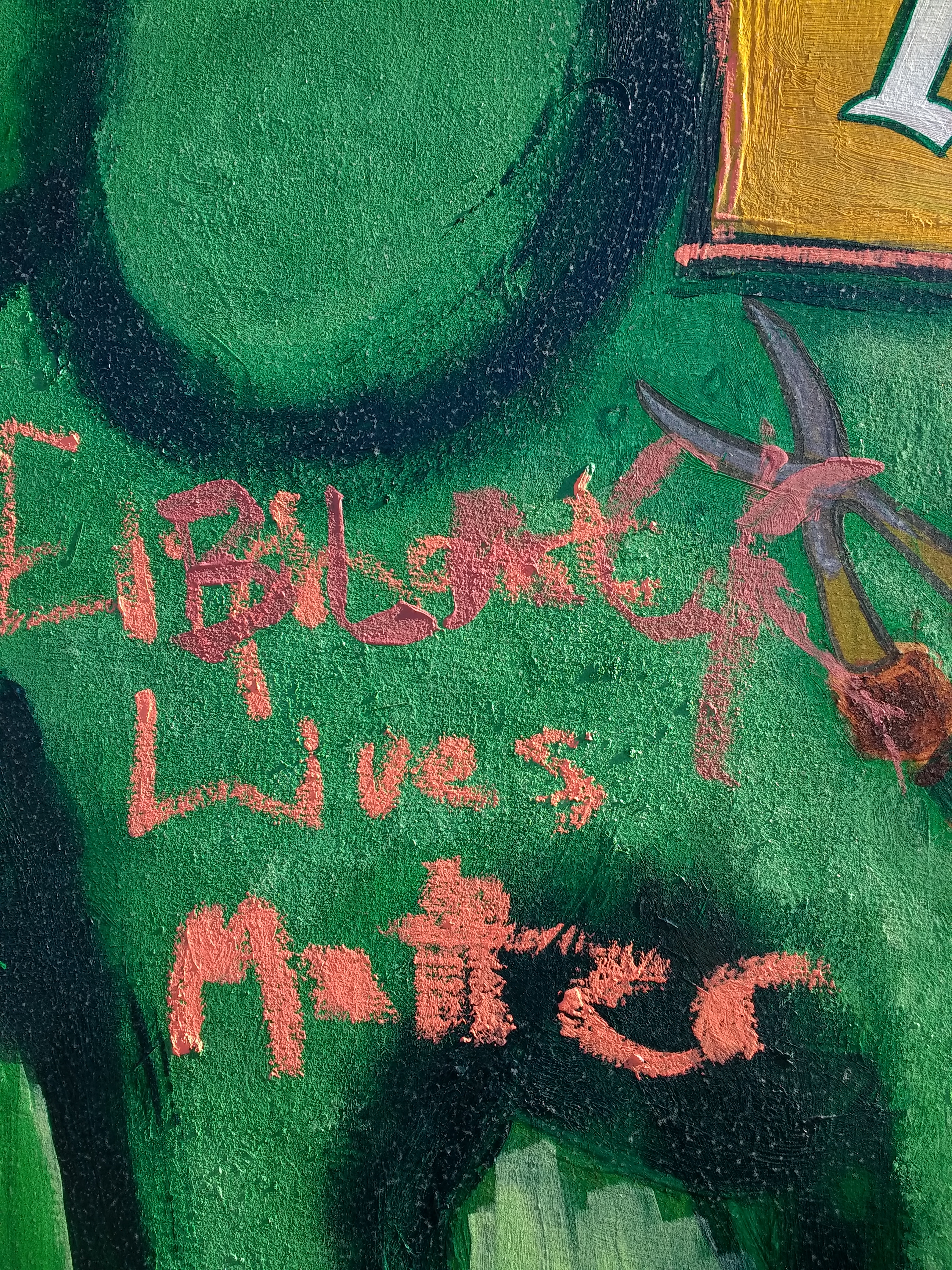

(Who painted “Elephant Lives Matter” on the elephant topiary? Who painted “BLACK” over it?)

I was a little intimidated by the East Bay Church of Religious Science, so I went in to ask the people at Kelly-Moore Paints if the paintings were theirs. “Because of… paint,” I found myself saying, and I began to feel awkward about it. After a pause to indicate that my question was extremely stupid, they speculated that perhaps the city put them there to discourage, in their words, “the less nice kinds of painting.”

This is a good speculation, I think, for a neighborhood with a lot of speculators. Temescal is one of the most aggressively gentrified parts of the city and maybe the most heavily painted, the part of the city that’s changed the most since whenever the last time you saw it was. And while you can definitely find “the less nice kinds of painting” if you look for them, in the shells of abandoned buildings, or on some of the less well-regarded walls—if much of Temescal is still “gritty,” still “weird,” still not quite like what a neighborhood like Rockridge has become, a decade or two earlier—you will find, as you walk along Telegraph Avenue marveling at the mutability of cities, that most of the painting is of the obviously official nature, like these, or the “Temescal Flows” mural adorning a nearby overpass.

Such painting is the hallmark of gentrification—if not its driver, then drawn along in its wake—and while that overpass was the historical line that separated the yellow parts of the map from the red, the fact that it’s been absorbed into the “nice paint” zone tells you something about the direction things are going. Or have already long gone.

Some more googling turns up that the paintings were painted by “students in classes taught by Ray Patlan at California College of the Arts.” But actually, maybe that wasn’t the question I was asking.

But let’s get closer.

So here is the thing: some nameless person painted “Elephant Lives Matter” on the elephant, and then—as I reconstruct this drama—someone else painted the word “BLACK” over top of it.

The first is a joke, a dumb sort of riff on the oddness of the Athletics’ elephant fetish. The story is this, more or less: someone once told the owner of the team, a century ago, that he had purchased a “white elephant”; across many moves, as the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City and then to Oakland—because Westward the Course of Empire!—they are still called the Athletics, and they still have an elephant on their uniform.

“Elephant Lives Matter,” if it’s more than a joke, could conceivably be a reference to the Trump decision to repeal laws against importing elephant hunting trophies, announced and then taken back. Conceivably. it might be asking too much of that joke to note that there certainly is a long history of white conservationism’s being very particularly focused on certain kinds of animal life—in Africa and elsewhere—while leaving other kinds of (human) life unmentioned, and unchampioned. Is it relevant that Temescal is where, historically, there has been one of the largest populations of Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrants in the city?

Sure, why not. But if it’s hard to read into that first joke—because jokes can be hard to pin down—the slipperiness of it is something, in its own right: you may not be certain what it means, but you can be certain that you aren’t certain.

By contrast, the addition of “BLACK”—in ALL CAPS on top of a more casually caps-and-lowercase script—is firm and impossible to mistake.

It isn’t a joke. It isn’t a riff. It’s not playful, not light. It’s simple, a repudiation of the joke and an insistence that a phrase isn’t infinitely mutable. No, it says, that’s not what that’s for; the phrase is not for joking, not for playing, not for multiple interpretations. “Black lives matter” is how the phrase goes, and that’s how it will stay.