Popula Editor’s note: Mada Masr is an Egyptian publication that is close in spirit to ours, covering news and culture in a raw and honest way. They also run gorgeous comics! Mada Masr co-founder Maha ElNabawi writes, “We’re still operating and publishing, but the site is again blocked in Egypt. We’ve also been under a lot of pressure with the upcoming cyber law that is meant to pass soon, as yet another measure to obliterate press freedoms.”

We’ll be publishing pieces from Mada Masr in the coming weeks, beginning with this series of letters from 22-year-old Abdelrahman al-Gendy.

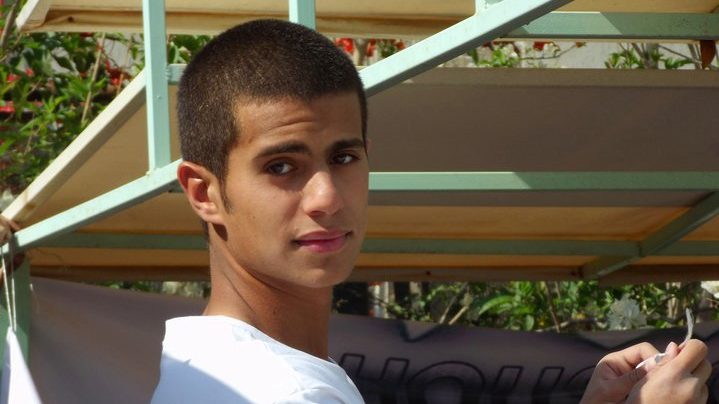

Mada Masr Editor’s note: 22-year-old student Abdelrahman al-Gendy was arrested from a car in Ramsis Square, Cairo, with his father in October 2013, several months after the ouster of former President Mohamed Morsi. They were charged, along with over 60 others, of murder, attempted murder, vandalism, possession of weapons and disturbing the public peace, and were sentenced to 15 years in prison, five years probation and a LE20,000 fine by the Cairo Criminal Court on Sept 30, 2014. In March 2016, their final appeal was rejected by the Court of Cassation. Gendy had won a scholarship to study engineering at the German University in Cairo and was not yet 18 years old when he was arrested. He lost his place at the university as a result of his imprisonment, and is currently enrolled at Ain Shams University and studying from Tora Prison.

The following letter was translated by Katharine Halls and Nahla Awad and edited by Laura Bird at Mada Masr.

Tora, May 9, 2018

When I saw him for the first time I was standing by the window on the floor where my cell is, watching the sky from behind bars during exercise hour. I turned to find him sitting in the squat position that prisoners learn, his back against the wall; he was thin to the point of frailty, short, with a thicket of frizzy hair. At first glance something about his face seemed different, and looking closer, I could see he had Down’s Syndrome. Any normal person would be surprised to find someone like him in prison, and not at a special needs facility — even more so to hear that his case was political. But I wasn’t surprised. I’m not surprised at anything any more. He was holding a cigarette and dragging on it as if his life, rather than his death, depended on it.

I approached him, watching his thin, pale, childlike face, then sat down beside him and asked him his name. He looked at me in astonishment and disdain; perhaps he’d been expecting the stream of mockery and bullying that he’d no doubt grown used to in this place where sympathy and humanity — on the part of both prison guards and prisoners — simply withered away with time. When I asked him again he looked away and ignored me. I asked a third time. He glared at me for daring to interrupt his moment of contemplation, and spat: “Ammad!”

Not understanding what he’d said, I repeated my question and he repeated his answer: “Ammad!” Someone walking past laughed and told me his name was Mohamed, but due to a speech defect, he could only only say it that way. Later, I was to learn that the whole prison called him “Ammad.” I took a small piece of candy from my pocket and offered it to him. He looked suspiciously at my hand, and then my face, then very slowly reached forward, anticipating whatever nasty trick would soon have us all laughing at him. His hesitation was perhaps to be expected from someone who had seen nothing but cruelty and would trust no-one, no matter how kind.

He took the sweet at last and devoured it straight away. I watched in amusement, then held out my hand. “Abdelrahman,” I said. He stared back, at a loss, until I realized that the name was too long for him to say. I tried again: “Gendy.” I said it a few times, till suddenly his face lit up with a great smile and he pronounced the word that officially announced our friendship: “Shengy!”

I began to say hello to him every few days. No one visited him and he owned nothing. He took to dropping by my cell for a little tea or sugar, or a cigarette; as far as I could tell, that was all he lived on.

One day, passing in front of his open cell during exercise hour, I saw him coming out of the bathroom after showering, dressed only in a long white undershirt that came down to his knees. One of his cell-mates started to tease him and tried to lift it up. Ammad roared with laughter and ran away. Instantly it became a game, with everyone in the cell chasing Ammad and trying to pull up his shirt while he bounded and circled around them, his loud guffaw echoing down the wing.

A few days later I awoke to a hand shaking me and a voice saying “Shengy! Shengy!” I opened my eyes with effort and asked, “What d’you want, Ammad?”

“Ummaya,” he said.

I asked if he wanted water, which was what it sounded like.

He shook his head, frustrated at my stupidity, looked around, found a cup and grabbed it: “Ummaya!”

“Ah, kubbaya?” He nodded happily. He’d lost his cup. I handed him a spare plastic cup I had. He took it in delight and showered me with a torrent of words I couldn’t understand, but which emanated a gratitude that filled me with a strange sorrow. How easy he was to please! All it took was a plastic cup that wasn’t important to anyone. I longed for those days when my happiness, too, lay within such close reach.

The last time I saw him he was coughing violently and yelling to be taken to the clinic. Everyone ignored him as usual; he was an “imbecile,” after all, so why shouldn’t we expect him to rave? I watched him go up the stairs to his cell still shouting in fury, repeating a phrase that only those privy to his personal lexicon could understand. “I swear to God we’ll die here!”

Two days ago I found out he’d fainted after a bad fit of coughing, that he’d been taken to hospital, and that he had tuberculosis. I don’t know if Ammad will die. I don’t know if I’ll ever hear that familiar call — “Shengy!” — again.

I’ve decided to write about him now before news of his death reaches me and I no longer care to hold a pen. I won’t feel like writing when the little patch of innocence and light that has attached itself to my soul withdraws, leaving me in the darkness again.

I feel revulsion at a universe in which I don’t know whether I ought to pray for him to live or die. I think I’ll pray for him as I pray for myself: that we should have peace.

Abdelrahman al-Gendy

Tora Maximum Security 2

May 9, 2018

Tora, June 26, 2018

Ammad died on the first day of Eid [June 15].