I’m late to court, but it doesn’t matter because court is also running late.

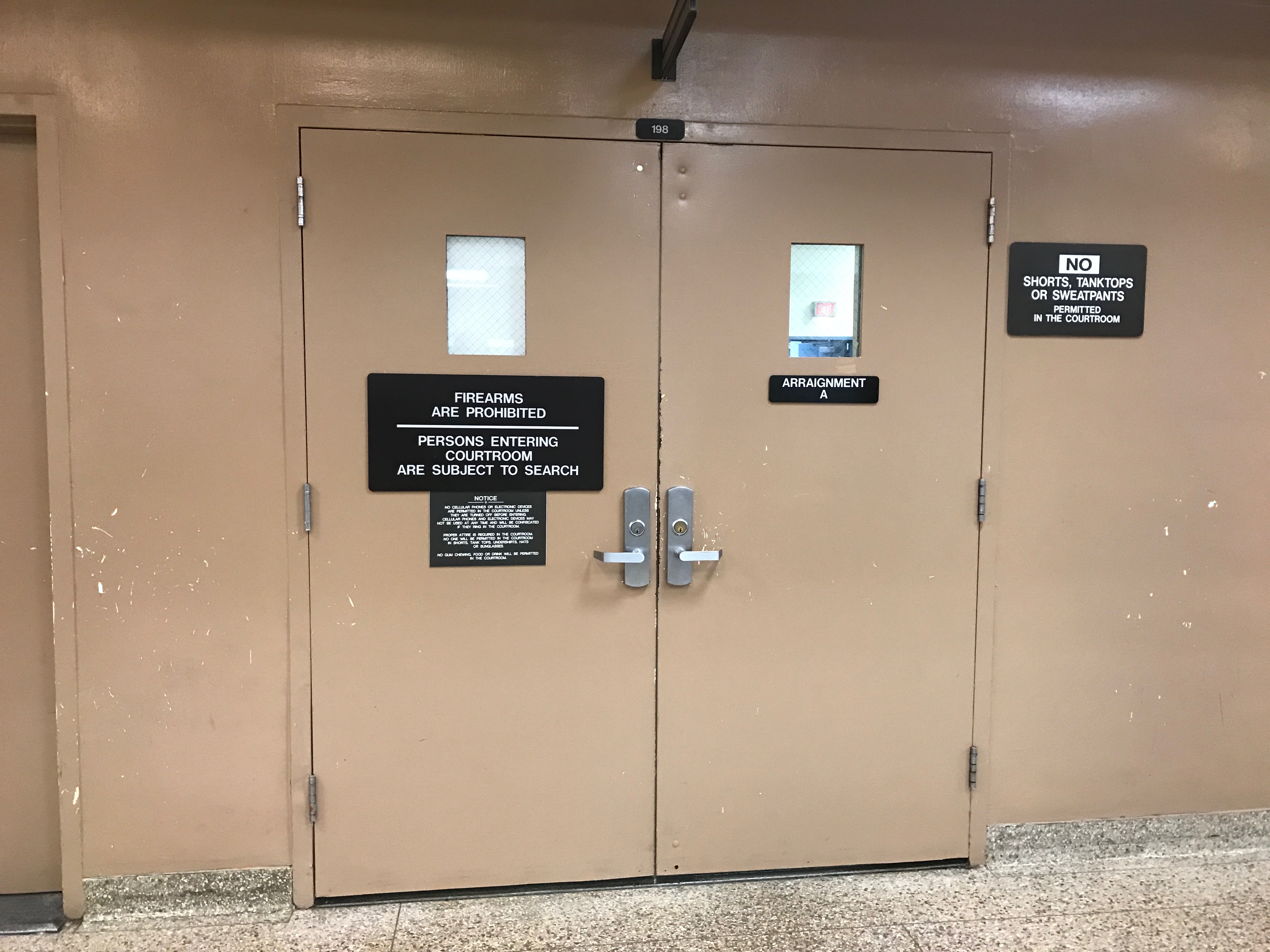

It’s not my fault I’m late; the train is delayed in the station in Brooklyn, and when I get off at West Hempstead, the bus doesn’t come. The bus doesn’t come and doesn’t come, so eventually I get into a cab, which costs $7 and drops me off at about 9:45 a.m., 15 minutes after arraignments are scheduled to start in Nassau County District Court.

This doesn’t seem important, but when I get to court, the benches are packed and there’s no judge in sight and a lot of people are talking about their commutes. There’s a private attorney sitting in the front bench, cracking jokes with a man who handles paperwork for the judge who’s reading the New York Post. That man says he’s transferring soon to another court, which will make his commute 10 minutes shorter on both ends. The attorney says he rarely gets over there; another attorney in his office likes to handle cases because it’s a short commute for him.

A few minutes later, the attorney trades war stories about the Long Island Expressway with another clerk. “Summer mornings are okay, but summer afternoons are just like winter afternoons,” the clerk says. There’s a joke I can’t quite hear about a kind of traffic violation meriting the death penalty.

The couple next to me, whose son spent the night in jail, are getting anxious, because by now it’s 10:30 and the judge is nowhere to be seen. Maybe commuting also, or maybe we’re waiting for the people on the bus from Nassau County Correctional Center to the courthouse.

One of the things people don’t think about enough is the organization and striation of the nation into states first, counties second, and cities and towns third. Counties get forgotten about, at least in urban America. Most city dwellers contemplate their counties only during election season, when they light up red or blue on CNN’s maps. But counties are often the centers of enormous power. Counties have sheriffs, courts, sometimes their own legislative bodies. They provide all kinds of municipal services to broad swaths of the country. Counties are bundles of disparate cities, towns, highways, and land, organized underneath a structure of power. Like this one, they can often feel opaque and procedural but are actually quite important.

Nassau County is squarish on a map, a chunk of Long Island that’s an easy commute to New York City. The county has a population of more than 1.3 million people, and it’s one of the highest-income counties in the country. “Nassau County high school students, as do students from nearby Westchester County, often feature prominently as winners of the Intel International Science and Engineering Research Fair and similar STEM-based academic endeavors,” the Wikipedia page about Nassau County tells us.

The judge enters and we all rise. She bangs her gavel, and court is in session.

The first case is a domestic violence felony case, and the defendant has a private attorney. The attorney argues that it should be an aggravated harassment case instead, and his client denies the charges. The judge sets bail for various charges: $2,000 bond or $1,000 cash, and $500 bond or $250 cash. The accused man is youngish, perhaps in his 30s, and his mother stands at the railing that divides the benches and the court, watching.

It is a morning of many domestic violence cases—15 of the 27 arraignments before lunch are for assault of some kind. Only one of these defendants is a woman; most of the victims are, though sometimes the names of victims are withheld, so it’s hard to be sure. As the cases are sent forward, and next court dates are set, the clerk often refers to the cases as “DV,” which is shorthand that cops and courts use for domestic violence. I am averse to this kind of abbreviation, which flattens real lives into acronyms and strings of numbers, though on a morning like this it’s easy to see why things get compressed: DV DV DV DV DV.

The judge issues a no-contact order in each one of these cases for the alleged victim. She is very firm with the defendants—sharp, perhaps, though that term is unfairly gendered. She tells them that they cannot contact the person by any means, including Instagram and Snapchat and Facebook. They cannot attempt to contact the person through another person. Sometimes the defense attorneys object to the no-contact order, often when it will render the person homeless because they live with the victim. But the judge never wavers on the no-contact orders. She also orders that they surrender their firearms, if they have any.

The defense, mostly handled by the same two public defenders, often feels like the reading of a strange kind of resume. “He has lived in Nassau County his entire life,” one defense attorney says repeatedly about her clients, as though staying put is a corrective of sorts to the crimes they’re accused of. He attended Hempstead High School. His parents are in court with him today, she says, gesturing back at two people who are standing at the railing behind one of the men accused. The parents appear guilty too, in this posture, somehow implicated by association.

The judge doesn’t want details. She gets frustrated at one of the assistant district attorneys, who tries to restate the facts of a domestic violence case for effect. “I have the complaint. You think I didn’t read the complaint?” the judge asks. When the prosecutor meekly objects, she snaps: “I run my courtroom the way I want to run my courtroom!”

I am straining for details. I admit that when they do emerge, over the judge’s objections, I find it hard to sympathize with the accused. A woman has been nearly pushed out of a moving car and strangled, the prosecutors say (and the defense denies the allegations). Another woman has been thrown to the ground. Another woman has been threatened repeatedly and attacked. Believe women, I believe. Innocent until proven guilty and often even after that and actually innocence is somewhat irrelevant a lot of the time, I also believe. But this muddled belief turns out to be less visceral than the image of a woman being shoved from a moving car, which has been thrown like a gauntlet into the courtroom.

It is possible to hold all these things in one’s head at the same time, I know, because I usually can: to believe that the criminal justice system is corrupt while also believing that protections for victims of domestic violence are enormously insufficient. Holding these both in mind is less easy in the public theater of the courtroom.

The no-contact orders are comforting, a useful function of a court, though in practice they seem difficult when lives are so deeply intertwined. The judge issues one in favor of a woman whom she calls “Beth Ann.” The man speaks up and corrects her. “That’s Betty Ann,” he says. Another man breaks down weeping when a no-contact order is issued between him and another man. “But he’s my best friend,” he says.

A pregnant woman has come to see her boyfriend in court. “Anger issues,” she told someone who asked why he was arrested. When he’s called, she stands behind the railing and cradles her stomach. The defender gestures to her and talks about how the man has been saving money for his child. The prosecution says he had multiple loaded guns and assaulted a 78-year-old man. His bail is set to $100,000 bond or $50,000 cash, and his girlfriend walks out of the courtroom crying.