In 2012, an incident involving a migrant from South Asia who worked in Dubai’s Al Aweer vegetable market was reported in the local media. As the story goes, he was an Indian porter who decided after finishing his shift to spend the night in the market. He was too exhausted to take the long trip “home” to a neighborhood called Hor Al-Anz. The journey from the market, which was moved from a more central location in 2003, to Hor al-Anz takes no more than 20 minutes by car—but by bus it would be much more than that, maybe a couple of hours. In all likelihood he shared a room with countless other workers in one of the shacks dotting the dilapidated neighborhood. It was probably not a comfortable place to live, so the decision to stay in the market might not have been a particularly difficult one. Since it was too cold to sleep outside, he chose to sleep in one of the shipping containers, which held numerous bags of onions. The doors closed, and he settled in for a night’s sleep. Unbeknownst to him, however, onions absorb oxygen, and they sucked all the air out of the confined space. The next morning, when other workers opened the container, they found him unresponsive. He was dead.

All that we know about the porter is that he was 55 years old, hailed from Tamil Nadu, and was identified by his initials, S. B., as is customary for anyone involved in criminal investigations in the UAE. The affair was soon forgotten, buried under the constant onslaught of stories about the city’s miraculous recovery from the financial crisis and the incessant construction of towers, hotels, malls, and theme parks that followed. Stories involving the trials and travails of workers may merit a shrug, or at best a brief interlude of compassion. But then our gaze turns away from the countless, faceless, and anonymous workers encountered throughout the city. But they are here—in construction sites and bus stops, or sitting under the shade of a tree during the few hours of rest given to them during the city’s hot summer months—and cannot be unseen. They are bussed to and from their accommodations, sitting in vehicles with no air conditioning, looking towards the distant skyline they have helped create but which is as remote and inaccessible to them as one can imagine. They are Dubai’s invisible residents, an underclass whose entire existence in the city is predicated on temporality and transience. Yet each and every one of them represents a story of aspiration and hope. What are these stories? What can we learn from getting a glimpse of their daily lives?

Soon after the “onion incident” was reported, I decided to visit this vegetable market and experience something of the environment in which the porter worked and ultimately found his demise. As I walked in the midst of the people there, my intention was to observe them without disturbance and to take photographs while they carried on with their tasks. In many ways I was trying to follow in the footsteps of photographic pioneers who captured the daily lives of ordinary citizens, those in the lower (as well as the upper) strata of society. They include Robert Frank’s magnificent ode to The Americans and Paul Strand’s haunting images of Depression-era America, and elsewhere in the world, that sought to celebrate people’s “everyday heroism.” And of course Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose portrayal of Mexican street workers, Indian children, and Parisians traversing their city was an ode to his subjects’ humanity, poise, and grace. These photographers’ choice of subject, composition, and framing were not based solely on aesthetic criteria; they were also a form of social commentary. In the images, those at the margins of society, the neglected and forgotten, were elevated to a higher status and in that way were accorded respect and dignity.

I had these precedents in mind as I began my journey capturing many images of those inhabiting this space at the far edge of the city. Al Aweer vegetable market is reached via a multilane highway leading to the next-door emirate of Sharjah. It is surrounded by a bland suburbia comprised of villas occupied by Emirati citizens, and a low-income district called International City anchored by Dragon Mart, the largest trading hub for Chinese products outside of mainland China. And, of course, an endless expanse of desert.

The market itself is comprised of three yards, specializing in produce from the local region, India, Pakistan, and Iran. Spread throughout are loads of watermelons, oranges, and garlic; heaps of limes, carrots, and pumpkins, and of course what seems like an endless supply of onions. There are also retail shops and storage units surrounding these yards, in addition to a couple of cafeterias. Feeling adventurous, I had a cup of karak tea, a spiced concoction common in South Asia that has become a mainstay for many residents in Dubai. (As things go, it has been commodified to the extent that it is being sold in gas stations through automated machines.)

I made my way through the market, carrying an assortment of photographic gear. This seems to have captured the attention of a young fellow, apparently from Kerala, who asked me to take his picture, which I gladly did. The whole affair took less than a minute, and we parted ways.

I am not sure about his motivation; why was he so keen on having his picture taken by a stranger? When I inspected the image during processing, I noticed the inscription on his T-shirt, superimposed on a couple of palm trees, which read: “Dubai, We the Kings.” This regalness was unmistakable in his demeanor as he posed in front of a stranger’s camera. Despite the derision South Asians face in the UAE, Dubai is a city of dreams for many of them, a place that one aspires to. The expressions Dubai Chalo (“Let us go to Dubai,” in Urdu) and Visa Dubai da (“visa for Dubai,” in Punjabi) are common in Pakistan, and are akin to a kind of “westward ho”; in that sense, Dubai is a modern-day El Dorado or Shangri-la—a place of riches. I also saw a form of connection to the city. Wearing this T-shirt, putting it on in the morning before heading to the market, seems like a small gesture that nevertheless proclaimed his belonging in a country that inherently rejects migrants like him as citizens. In standing defiantly, proudly, he undermines this notion. He is not some degenerate “bachelor,” as migrant workers are referred to by officials; he is a person who contributes to the city’s development. It is almost an act of subversion against the all-encompassing, overwhelming, hegemonic city. In his mind, he is the King of Dubai.

In the seemingly soulless and anonymous cities of the Arabian Peninsula, South Asian men seek each other’s companionship as a way to mitigate the harshness of their daily lives. As I was moving in the market, amidst all the hustle and bustle of porters, merchants, and customers, I frequently encountered groups of people sitting together, chatting and watching the scene around them. What was so remarkable to me is that in coming together they were forming—albeit briefly—a community of sorts in a city that seeks to separate and isolate. In such instances the city recedes into the background, and perhaps for a brief amount of time they can forget about their transitory status. The smiling and amicable faces suggest an acceptance of sorts—but they also betray a darker side, which comes through when one encounters some solitary figures who are present as well.

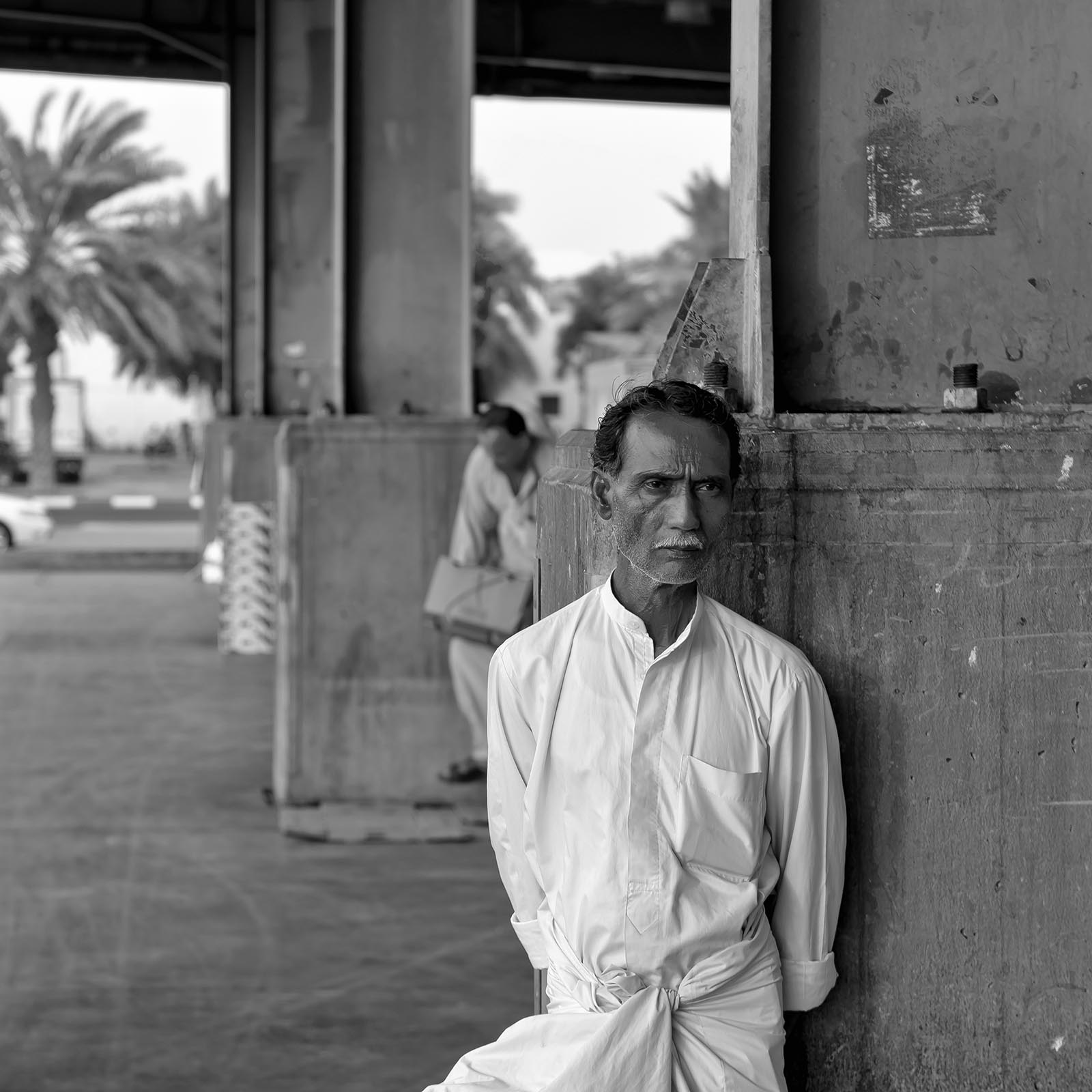

Indeed, one of the most haunting images I captured on that day was of a porter leaning against a column. The photograph shows an elderly South Asian man wearing his traditional garb while in a moment of rest, deeply reflective—unaware of my presence. There is sadness, a sense of helplessness in his face, which I have also seen in the faces of other men as they go about their relentless, Sisyphean tasks, day in and day out. And it was perhaps upon viewing the photograph that I began to better understand the ambiguity that characterizes the lives of such migrants—a sense of camaraderie and solace is found in each other’s presence, but the longing for home is intensified by their tenuous residency and transient status.

In a city that views migrant workers as disposable commodities, their very presence and defiance counteracts this premise. In a city whose entire raison d’être and ethos are predicated on temporality and transience, wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the word Dubai, gathering in a group, or leaning against a column is a small act of defiance. But there is a downside: resistance does not always work, and there are those who fall by the wayside, asphyxiated in a container full of onions or perishing from heat exhaustion in a construction site. Some even decide to take their own lives in an act of desperation. Indeed, since 2014 more than 450 Indian migrants have been shipped home in body bags. Ultimately, a city where coming together in some remote locale is the only recourse for the marginalized and forgotten to find some solace is unjust and fragile. In explaining the title of his novel Cities of Salt, the Saudi novelist Abdelrahman Munif said, “When the waters come in, the first waves will dissolve the salt and reduce these great glass cities to dust. In antiquity, as you know, many cities simply disappeared. It is possible to foresee the downfall of cities that are inhuman [. . .] they won’t survive.”

I do not know whether cities in the Gulf will eventually disappear; I certainly hope not. But for these cities to have any shred of legitimacy and credibility they must acknowledge the army of invisible residents who traverse their streets and spaces. Their stories need to be told and their humanity accepted, and not just through a few token gestures and gimmicks, but by making them an integral part of the societies they have helped build.