“Every time you turn around somebody’s calling somebody else a red,” laments Henry Fonda’s character, Tom Joad, in The Grapes of Wrath. “What is these reds anyway?”

Seven years after the release of John Ford’s film adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Dust Bowl epic, the House Un-American Activities Committee began asking more or less the same thing about the film industry. At the time of Fonda’s question, though, a more pertinent question for Hollywood might have been, “Where are these reds anyway?” They certainly weren’t appearing at the local Bijou.

It’s not as though radicals were invisible. By 1940, the Communist Party was an ubiquitous intellectual presence on the cultural landscape of New Deal America. More important, through its influence in the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the CP was helping to guide a vast and growing labor movement. And the activities of those enamored with the collectivist dream weren’t confined to mere politics.

“There were a lot of fraternal, literary and sports organizations,” Harry Kelber, a longtime labor activist, once told me of that fervent time, adding that that kind of total immersion and overlapping of politics and culture has vanished today.

Yet images of agitators of any stripe were kept out of movie palaces far more easily than the real things were barred from America’s factories and fields. Even if a film bore a social-justice theme, its radicals were routinely prevented from trespassing onto the screen.

In The Grapes of Wrath, the reds who were so mysterious to Tom Joad were dispatched with a single line written by producer Darryl F. Zanuck.

“I ain’t talking about that, one way or another,” is how Fonda’s boss brushes off the potentially controversial subject raised by Joad.

In Steinbeck’s novel, capital’s reply is less evasive: “A red,” Tom is told, “is any son-of-a-bitch that wants thirty cents an hour when we’re payin twenty-five!”

Although more comment is usually spent on Zanuck’s crafting of Ma Joad’s “We’re the People” monologue that optimistically replaces the book’s grim ending, his airbrushing out of the Left from the Depression is a no less breathtaking feat.

As an art form dense with dialogue-driven narrative, film does not easily transmit political messages. And, because film is the most commercial art form in this country, American movies are rightfully hailed as among the least politically conscious in the world. Outside of some independent features, such as King Vidor’s Our Daily Bread, or a relative handful of leftist documentaries, American moviegoers during the 1930s had no reason to suspect they were living in the midst of the Red Decade.

Later would come unflattering Cold War films made about American Communists and even a few wartime movies sympathetic to the USSR, but during the Great Depression – the high-water mark of domestic radicalism — hardly any movies touched upon the home-grown radical experience. This fact, freely admitted and lamented by CP screenwriters, would one day make life hell for Congressional investigators seeking evidence of a vast conspiracy to insert party propaganda into Hollywood’s dream machine.

Offhand I can only recall two mainstream films that came close to answering Tom Joad’s question. William Wyler’s screen version of Elmer Rice’s play, Counsellor at Law, has an electrifying political speech angrily addressed to the main character. The tirade is delivered by Harry Becker, a young radical thrown in jail for speaking in Union Square. He is the son of an immigrant woman who is a friend of the titular lawyer, George Simon.

“You mean Harry’s been going around making Communist speeches?” asks John Barrymore, portraying the high-flying Jewish attorney who rose from the streets of New York. Harry eventually appears in Simon’s lavish art deco office, but not to thank him for fixing his case with the D.A.’s office.

“How did you get where you are?” shouts Harry. “I’ll tell you – by betraying your own class, that’s how! By climbing on the backs of the working class, that’s how. Getting in right with bourgeois politicians and crooked corporations that feed on the blood and the sweat of the workers!”

It’s a spellbinding moment in Depression-era filmmaking – a venomous class harangue that goes mostly unanswered by Barrymore’s character. Harry, his face bruised from a police beating, was played by Vincent Sherman who, even if he hadn’t been later blacklisted for his alleged Communist associations, surely earned it for this heated performance.

As far as a story filled with wall-to-wall reds is concerned, one has to fall back on the politically bowdlerized adaptation of For Whom the Bell Tolls – which is, after all, a World War II-period film that doesn’t take place in America. The movie, which offered a jaundiced view of the forces fighting for Republican Spain, starred Gary Cooper and was directed by Sam Wood – two deeply conservative men who in 1947 would eagerly testify against their Hollywood colleagues for HUAC.

Except for these two examples, audiences had to get their taste of radicals wherever they could find them. “Reds,” of course, were hardly the only group absent in Hollywood’s presentation of the American experience, and they certainly weren’t the most noticeably absent. Still, picking out coded radical references in old films, or occasionally finding acknowledgments of the labor turmoil engulfing America during the Depression, is always a fun pastime today – sort of like spotting submerged gay allusions or sexual double entendres in Hays Code works.

Some of the works were made by sympathetic auteurs like Orson Welles, while others, like the screwball comedies of the staunch conservative Howard Hawks, were written by decidedly non-communists like Billy Wilder.

Welles’ Citizen Kane has several conversations referring to the working man who’s “turned into something called ‘organized labor.’” The first occurs in the “March of Time” newsreel spoof, where a Union Square rally is recreated at which a party hack declares the film’s subject, Charles Foster Kane, to be “what he always has been, and always will be – a fascist!” Another scene comes up when the newspaper tycoon Kane, played by Welles, warns his lifelong antagonist, Walter Thatcher, that if it weren’t for empathetic people with “money and property” like Kane looking out for the poor, the latter might turn to “somebody without any money or property – and that would be too bad.”

But this is all overt stuff compared to the rest of Hollywood fare. Beyond Kane’s ominous prediction it’s necessary to break out the drift net and trawl for the don’t-blink throwaway lines of snappy comedy, the little gags that tip us off to the big picture then unfolding off-screen. Take Barbara Stanwyck’s description, in Hawks’ Ball of Fire, of her inflamed throat being “red as the Daily Worker and just as sore.” It’s a line that coolly acknowledges the presence of a radical newspaper; the fact that there’s no comment or explanation suggests audiences were well aware of the Daily Worker and what it stood for.

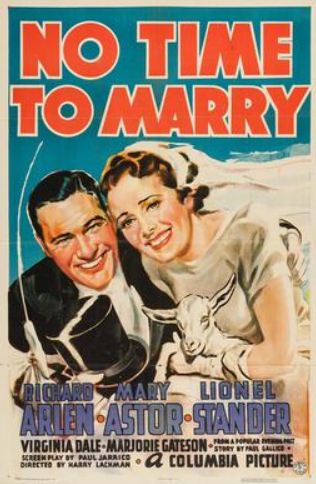

Then there’s Lionel Stander’s famous improvised whistling of a few bars from “The Internationale” as he awaits an elevator during No Time to Marry. Stander, a longtime radical (and blacklist hall of famer), was proud of his stunt which, however, did little to endear him to his Congressional inquisitors years later. Here was a very rare case of a nod to working class solidarity being made not by a writer or director, but by an actor.

Stander’s gesture amounted to a middle finger — flipped not so much in the face of the capitalist system as the studio system and the tyranny embodied by front-office suits. For more of this kind of Oedipal defiance, we return to the scene in Citizen Kane, where Kane’s former guardian, the vinegary financier Walter Thatcher, asks the now middle-aged and broke Kane what he really would have wanted to be in life, had he not been raised in luxury.

“Everything you hate,” growls Kane, dropping the light banter that’s led to this moment, his face dark with contempt for the old man, played by George Coulouris. Thatcher, it is clear, is not simply a substitute father whom Kane despises, but a way of life he deplores.

It’s an answer that Harry might well have given George Simon, had the counselor asked the young radical what he wished for the future – or one given by Tom Joad to his boss, had that question about “these reds” been asked the other way around.