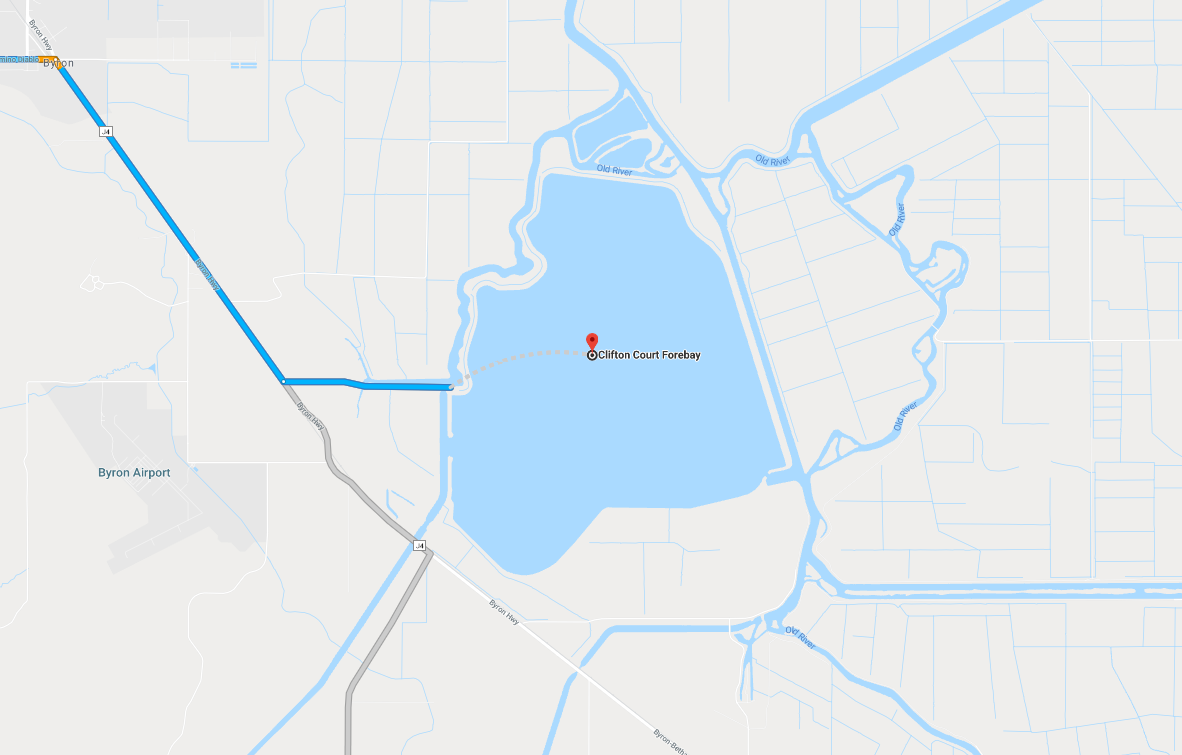

According to Google Maps, Clifton Court Forebay should be easy enough to get to. If you type in that name, as I did, you will be instructed to take the Byron highway down from Antioch, to turn off on Clifton Court Road—a paved, but markedly smaller side lane—and drive your gas-propelled vehicle past the Lazy M Marina until you reach an ad hoc parking lot. At this point, Google helpfully suggests that you take to the air for a dotted-line-leap to the center of your final destination, an artificial body of water at the center of the massive system of irrigation that makes California possible.

I would not suggest you make this leap; the water is gentle and cool and peaceful—enjoyed by the ducks and herons and the fish they are trying to catch—but I suspect there is nothing but water at the very center of this reservoir. There’s a lot to this water, though. It’s water that was blown off the Pacific Ocean, that fell as snow in the Sierras, that flowed down out of the mountains through the confluence of rivers that feeds into and forms the California Delta region, and then, from here—the calm center of the state’s water system—it will lazily find its way down to two intake points, the Harvey O. Banks Pumping Plant and the C. W. Bill Jones Pumping Plant; here, it will enter the great California aqueduct and be pumped hundreds of miles to the south.

On this bright and clear Sunday—while the internet debates Brett Kavanaugh’s teenage history as a would-be rapist—you will see about a dozen parked vehicles; most of their owners are within sight, mostly fishing, mostly alone. All hot rocks and dusty sun, a 16.2-mile trail appears to go all the way around the reservoir, though I haven’t yet tested the proposition. But it’s in good use. One man is on a bicycle, his fishing pole held high up in the air like the mast of a ship. Another man has a radio, playing distant music in Spanish; the sound bounces across the gently lapping water—its surface like a drum—making it difficult to tell where it’s coming from. The only woman I see—and the only other white person—is walking her dog. She greets me, the only other person who will.

I end up walking out along the Western side, where the blue of the sun is so perfectly mirrored in the water that the horizon seems like an arbitrary line.

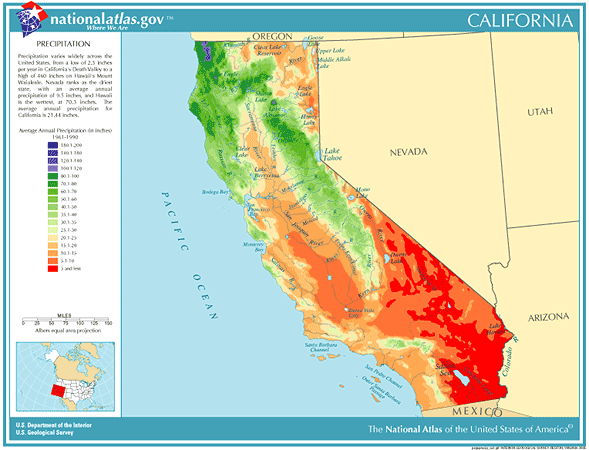

This blue is in the middle of a very dry state: California is essentially a desert. Most everything west of the Mississippi is, in fact; called “the great American desert” in the 19th century, you can see it on rainfall maps which show us in shades of gold how much less rain there is in the West than in the verdant green of the East. East of the Mississippi, there there’s abundant, consistent rain; west of it, broadly speaking, there isn’t.

California is a very golden state, in this regard. Or it would be: without large-scale irrigation—without the aggressive rerouting of water from the mountains into massive reservoirs and aqueducts, which branch off from there into hundreds and thousands of channels and arteries—California could not be green. Indeed, California, as we know it, would not be possible.

If you look at rainfall maps, you can see how green most of the state wouldn’t otherwise be, how the green of the long valley that gives the state its shape—a green you can see from space—is a function of irrigation.

This is why I went to Clifton Court Forebay. It might seem like a place to fish and hike and bike, and certainly it is these things, but that’s not why it’s here. It’s here because a system of dams, reservoirs, pumping stations, canals, pipes, and one of the world’s longest aqueducts were built in the 1960s to transport water from the mountains to the desert and make it into farmland. Stocking the reservoir with fish allows a fraction of the maintenance cost to be diverted to recreation, siphoning a small amount of money meant for “nature” into the cost of subsidizing agribusiness. Calling it a “recreation area” makes it seem like it’s something other than a giant water tank for Southern California located in Northern California.

Of course, Clifton Court Forebay does feel a lot like nature; I saw a heron, some ducks, and the fishermen are solid evidence for the presence of fish. But when there was some damage in one of the intake pumps last year (“just weeks after Oroville Dam crisis”), it was an occasion for the Sacramento Bee to note that “a third of Southern California’s drinking water” flows through here, as does the water for “750,000 acres of farmland in the Central Valley.” Clifton Court Forebay is not here because of fish. The fish are here because Clifton Court Forebay is here, and Clifton Court Forebay is here because of the California Aqueduct.

I drove to Clifton Court Forebay because I was curious what the center of California looked like, the point at which “natural” water becomes irrigated water as northern California’s mountainous abundance gets sent south to water the desert. The water in this reservoir made the first part of its journey powered by “nature,” by the combination of gravity and weather that do more or less what they did a century or a millennium ago. However precisely built and constructed and calibrated and maintained the entire delta water system may be—with its levees and channels all designed to maintain and regularize the otherwise “natural” flow of snowmelt into rivers—these waters have drifted passively, a gentle and easy semi-tidal gravitational movement.

What was newly built in the 1960s was the California Aqueduct’s two pumping plants, a pair of stations whose presence you can only intuit from the sharp, hard stop of the two grey ribbons winding south-ish from the reservoir.

At those hard stops, “nature” stops describing the way in which the water flows; at this point, the water’s flow must be described in terms of the electricity used to pump it upwards and down south. A fifth of the electricity generated in California goes to power the flow of water, so a lot of hydropower is generated here; the Delta is framed by windmills on every horizon and speckled with cows grazing under massive power lines.

From here, the water will follow four main branches: one pump sends water West, to San Jose, but the other sends water south—alongside the 580—into three main branches: the Coastal Branch feeds Kern county and the coastal cities of San Luis Obispo, Santa Maria, and Santa Barbara; the West Branch sends water to Los Angeles; and the East Branch distributes water to the Inland Empire.

This north-south artery is why the proposal to split California into six or three states is dead in the water; in a very concrete way, this is the water in which it was always going to die. The state of California has always been willing to divert its own water into other parts of itself, spending unthinkably vast sums of taxpayer money to send water from the north to support populations and agribusiness on the rainless lands to the south, but states have not historically been as generous with each other; when the California Aqueduct was built, in fact, California was busy fighting Arizona in the Supreme Court for the waters of the Colorado River.

These pumps and the Aqueduct are where “Nature” stops in another sense: fish will not be allowed to swim south. Just upstream from the pumping stations, Chinook salmon and Delta smelt have to be carefully dissuaded by an elaborate system of louvers, pipes, screens, tanks, and trucks that really has to be seen to be appreciated. The Department of Water Resources tells us that 15 million fish are re-routed in this way each year, but a statistic cannot capture what actually happens: fish that flow into the channel get pushed away from the intake into bypass pipes which separate them into a screening channel where they are pumped into circulating oxygenated holding tanks; twice a day, the fish are counted and measured and loaded into an oxygenated tanker truck which drives them back to upstream locations.

I was also re-routed, albeit more gently. If you try to drive to these pumping stations, you’ll get a “This route has restricted usage or private roads” warning on Google Maps, which will turn out to be true; every access point dead-ends in a gate or a fence. You won’t need to be screened and then pumped into an oxygenated water tank and then driven elsewhere on the delta; eventually, you will simply turn your car around and try another way, and keep trying, and keep trying, until you give up.

I drove around and around, attempting main access roads, and then other roads, and then some of the smaller farm-access roads—even when they turned into dirt roads—but all to no avail. The pumping stations also mark the point at which the water has stopped being public recreation, been transformed from nature into a natural resource, and a strategic infrastructure at that. It makes perfect sense that I was able to see neither the Harvey O. Banks Pumping Plant nor the C. W. Bill Jones Pumping Plant; can you imagine the damage a terrorist could do to the American Way of Life if they could shut down those two pumps? Homeland Security certainly can.

When global warming destroys California, this is how it will happen: instead of getting caught as snow and ice—and gradually melting to be time-released into rivers across the long dry months—the rain that blasts down in the winter will flow off the mountains, much too fast and much too strong, all at once. Rain-on-snow floods will prove too much for aging structures like the Oroville Dam, while the levees and the Delta pumps will fail or get washed away, especially if they happen to get hit by an inopportune earthquake. The entire system is built to manage the gentle flow of gradual snowmelt, having been built a half-century ago to contend with historic patterns; in the 21st century, climate change will mean that weather patterns will be historically volatile. The system will only be older and less well-maintained as the years go on, and as the seas rise and the weather’s cycles become increasingly sharp.

It will probably break. This could happen in a variety of ways; if it happens quickly, it will probably be because of a big earthquake. If it happens slowly, the death will be by a thousand cuts, and by the steady rise of the ocean. Most of the Delta is well below sea level and its “islands,” called that because they are surrounded by levee-reinforced rivers, are better described as bowls, waiting to be filled; if and when those levees are breached—say, by an earthquake—the Delta will become a salt-water marsh.

Though the volatility will come from the mountains—the rains and floods that will get stronger and less predictable—the real threat comes from the rising oceans. Right now, the ocean water pushing in from the San Francisco bay into the delta is met by a steady counter-flow, the fresh water flowing into the delta down from the mountains. There is a point at which they meet in the middle, and at the moment, this point is safely to the north and west of the pumping stations.

All the fresh water pushing against the ocean water keeps the delta “blue,” and because that brackish water is kept safely west of the choke point in the middle, freshwater in the delta is able to flow south towards Clifton Court Forebay and its pumping stations. If too much freshwater is diverted, the seawater will push its way in. And so, when the levees fail as the oceans rise, the delta will inevitably fill up with water: engineers call it the “Big Gulp,” as the Delta sucks salt water from the ocean until its low-lying thirst is slaked. When this happens, the delta will go back to being what Spanish explorers thought they were seeing when they looked down from Mt. Diablo, in the 1700s: a vast inland sea.

When this happens, Clifton Court Forebay will no longer be filled with fresh water. It will be filled with ocean water, and rather than pump that salt water south, its two pumping stations will shut down; a third of Southern California’s drinking water will disappear, as will the water for 750,000 acres of farmland in the Central Valley.

At this point, it will suddenly make a lot more sense to divide California into different states; if California’s highways are iconic, water is what makes this state something other than a desert. Without fresh water flowing steadily and manageably from the mountains, there is no Los Angeles; without fresh water flowing steadily and manageably from the mountains, there is no Central Valley; without fresh water flowing steadily and manageably from the mountains, there is no Bay Area. There was a California before Clifton Court Forebay, but I’m not sure there is one after it; without fresh water flowing steadily and manageably from the mountains, California is Nevada with a coastline.

As I drove around and around, I thought about how my vehicle’s internal combustion engine burns a geologic fuel formed over the course of millions of years, about how there was a time—quite recently—when people were very worried that we would run out of fossil fuels, and that modern civilization would collapse from the drought. These days, what will do us in is the surfeit, the excessive flow: we are burning so much of the stuff, so fast. We aren’t running out; the waters are rising.

Clifton Court Forebay was built in the late sixties, by Governor Pat Brown; when he was talking over his legacy with historians, he explained that the cost of building it was never an issue. “You need water,” he said; “Whatever it costs you have to pay it. It’s like oil today.” The aqueduct was built because it had to be built. But it was built long enough ago that hardly anyone really remembers how many people had to be moved or forced to sell their land to do so; it was built when huge works projects could simply force people to give way and let the state be remade around them. Pat Brown built the California Aqueduct because, in the 1960’s, a governor of California could do things like that.

Today, it’s not clear that you can do things like that. After Governor Reagan became President Reagan, Pat Brown’s son, Jerry, spent both of his tenures as governor of California trying to build a fix for this looming deluge. First, it was to be a peripheral canal and, now, it is to be tunnels that would simply draw water from the northern-most part of the Delta; instead of waiting for freshwater to flow down through the Delta’s web of rivers—keeping the Delta itself alive, by the way, and relying on its levees and channels —the tunnels would simply grab the water upstream, at the top, bypassing the Delta entirely. The advantage of this plan is that if and when the delta is flooded with salt water from ocean, southern California’s access to mountain fresh water will not be imperiled. When the delta dies, Kern County will keep cash-cropping.

It may yet; this may yet happen. And yet the plan now called “California Water Fix and Eco Restore,” has been stalled for a long time. Jerry Brown will likely leave office having not completed his father’s work, and his successors are strikingly less enthusiastic about it. In Pat Brown’s day, “whatever it costs you have to pay it” might have been a more persuasive argument, or maybe Pat was a better politician than Jerry. If it gets built, it will be because Southern California’s water districts have ponied up the cash. But if it doesn’t, it will partly be because of all the push-back from the delta itself, where you see “No Tunnels!” signs everywhere. Residents of the Delta understand that the purpose of the tunnels is to make the Delta expendable. The real purpose of the tunnels is to plan for the future, when the Delta is flooded.

I don’t know if this is a good thing or not; I don’t know if California is a good thing or not. These massive water projects are handouts to agribusiness and real estate investors, and have always been, but that’s the story of California; the damage they’ve done to what would otherwise be describable as pristine nature is impossible to even calculate, and many of the worst losses have been endured by California’s native people, upstream, but that, again, is the story of California. These modern mega-projects are built with a belief in the future poised somewhere between reckless speculation and religious faith, and some kind of self-imposed “natural disaster” will be what destroys their Ozymandian works; but this, again and again, is the story of California.

Not yet, though. Right now, I can still drive around the Delta in my gas-powered vehicle, listening to a radio program from Orange County in which the Association of California Cities hosts a discussion with “water leaders” and everyone gushes with enthusiasm for the California Tunnels. No one mentions climate change as the reason for their desperate optimism. I can imagine that you can hear it in their voices, that behind rhapsodies to reliability and sustainability, they know they are talking about sacrificing the Delta to survive the coming deluge. But maybe not.

Before I went home, I stopped off for a cup of coffee in the truly absurd cartography that is “Discovery Bay,” a planned community almost exactly the same size as Clifton Court Forebay, a few miles north of it. It’s a very Californian community, the way it rises up from the dusty farmland around it, marked off from its surroundings by arbitrary lines; like everything else, “Discovery Bay” would have been desert were it not irrigated by riverine canals with houses clustered tightly around every scrap of artificial waterway. It was built in the 1960’s—what wasn’t these days?—so that today, ten thousand or so people can “Live Where You Play,” as the town’s website proclaims; as you’re driving along, there it abruptly is, out of nowhere: a dense suburban residential development, with shopping centers and an 18-hole golf course.

I got a cup of coffee, and then drove around and around this truly strange maze of otherwise ordinary-seeming residential suburbia, trying to find somewhere to stop off and drink it; a marina, a park, any kind of public space where people go. As I drove, I wouldn’t have known except from google maps that the backyard of every house abuts against a single interconnected bay which flows all the way to the ocean; I wouldn’t know this because at no point could I see the water from the road. I couldn’t find anywhere to stop, so I kept driving.