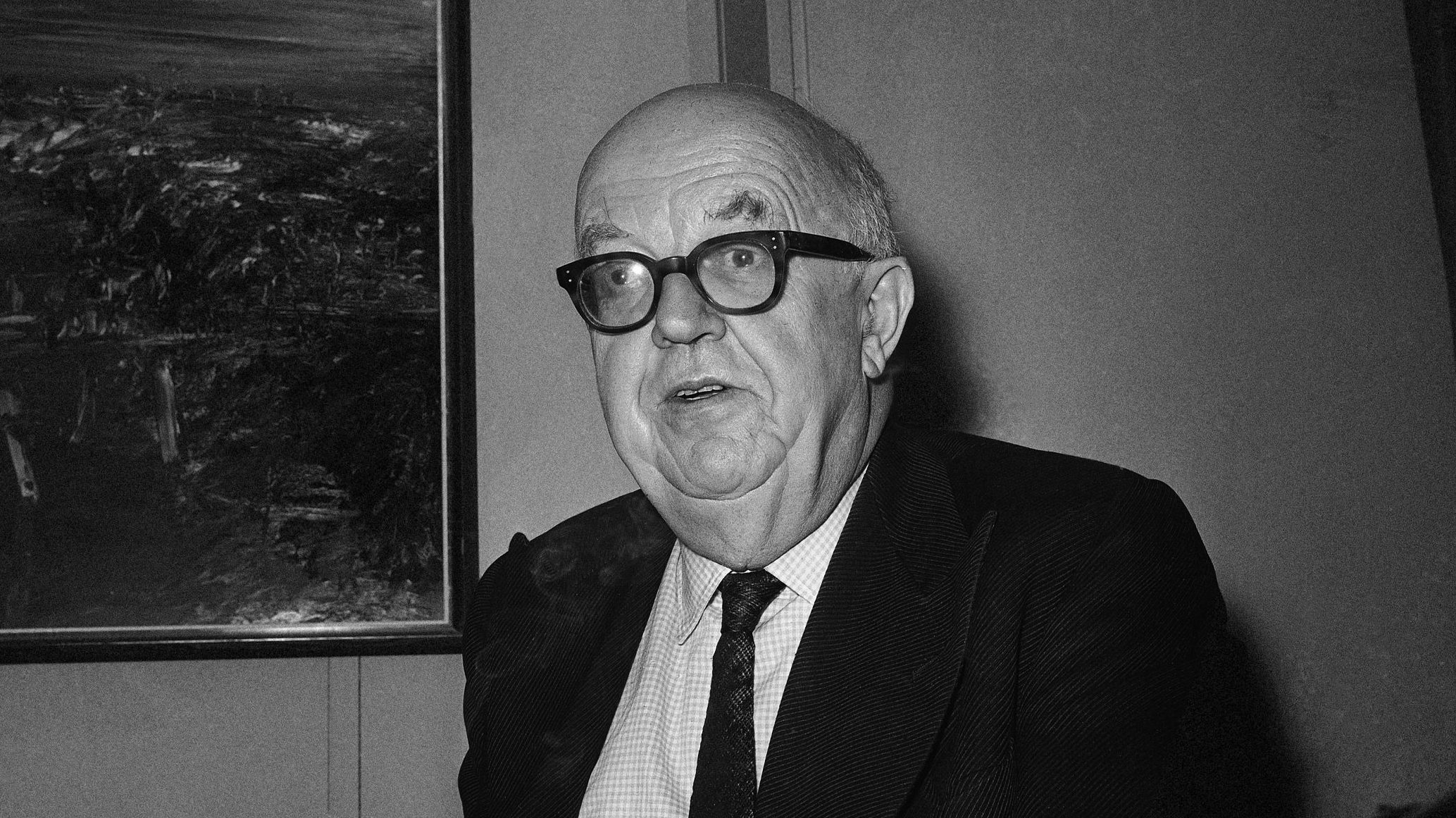

The English novelist and civil servant C.P. Snow (1905-1980) was a big, shambling man with a voice full of portent and the face of a bespectacled baby. A life peer, Baron Snow of the City of Leicester, he was knighted for his work hiring scientists for the Ministry of Labour in the second world war. But he is most famous for starting a fight that is still going on to this day. It began with a lecture, “The Two Cultures,” that he gave at Cambridge in February 1959.

In the postwar period it had seemed inevitable that scientific advances would put an end to poverty and want. Establishment men like Snow, in particular, considered science as a guarantee of human happiness and prosperity. As a novelist who’d originally trained as a chemist and physicist, he felt himself a senior member of both tribes, the literary and the scientific, entitled to speak with authority on pretty much everything. And so he attempted to build a career on the idea that literary culture in England was too dismissive of Science. Never mind that he’d failed as a scientist early in life; never mind that his novels were, and remain, unreadable.

Anyhow, in this lecture, “The Two Cultures,” Snow set forth a manifesto urging the “literary intellectuals” to get out of the way of the scientists, who “have the future in their bones.” Boo to the hidebound historians, belletrists and philosophers, and Hooray! for the brash, can-do fellows in their white coats leading the charge of Progress! The lecture became an instant sensation, debated feverishly in the press and the academy, and assigned as reading for university-bound students.

Beyond the scientific cheerleading, “The Two Cultures” relied on Snow’s paternalistic view of “the common man,” the real maker of progress who, he believed, would be set free by the open pursuit of materialist values: “Common men can show astonishing fortitude in chasing jam tomorrow. Jam today, and men aren’t at their most exciting: jam tomorrow, and one often sees them at their noblest.”

The elitist notion that poverty is itself ennobling—that working people should be forced to chase “jam tomorrow” as if they were so many horses on a track, and thus appear “at their most exciting” to people like C.P. Snow—is alive and well in the tax-cutting austeritarians of today, all still richsplaining about how the rest of us really ought to be pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps while they buy themselves another yacht or whatever.

On the surface, Snow had condemned the schism between the Two Cultures, and called for science education to be given equal stature with the liberal arts in English schools. Beneath it, more elemental forces were loosed.

As the sixties began, the Western democracies were highly receptive to cheerleading on behalf of Progress. “A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow” was coming.

Countless technologies were roaring to life at once, and a lot of them came with substantial benefits. There were magical breakthroughs in industrial automation and computers and medicine. Organ transplants, bypass surgery, the removal of brain tumors. Agricultural revolutions right and left. A certain summer evening came, after which nobody would ever see the moon quite the same way again.

Soon, very soon, everyone on earth would be fed, healthy, educated, prosperous—technology was making that inevitable—so why would we ever need another war? And the glorious crescendo of “progress” would come almost effortlessly, as if the human race were gliding toward a new Golden Age on a frictionless track: it was only a matter of time.

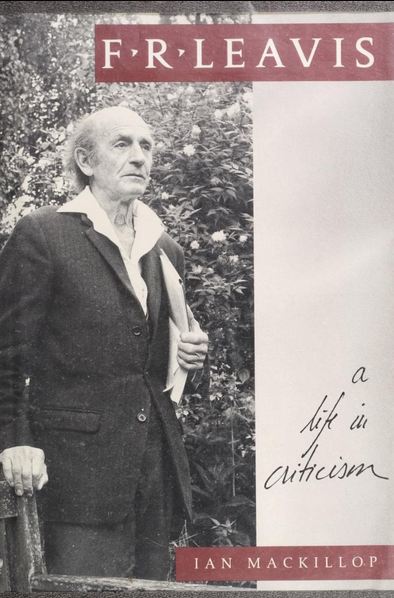

But certain observers remained unconvinced, among them the Cambridge don and non-fool-sufferer F.R. Leavis. He was some ten years older than Snow, and belonged to the hypermodern school of literary criticism that demanded that modern fiction be read seriously—a real heresy in late-1950s England. Leavis was a fiery advocate for D.H. Lawrence, at a time when most of his academic colleagues thought that Chaucer was plenty modern enough for scholars of English. A passionate champion of freedom of speech and thought, Leavis was the diametric opposite of the blandly conformist establishment man, Snow.

Leavis hated seeing Snow’s influence rise. When he learned that bright sixth-formers were being assigned to read “The Two Cultures,” that was the last straw. He mixed up a Molotov cocktail in lecture form, and in February of 1962 he hurled it at Snow before a Cambridge audience of his own.

“Two Cultures? The Significance of C.P. Snow” began with an appraisal of Snow’s novels, their “utter lack of intellectual distinction and… embarrassing vulgarity of style,” and things whizzed downhill from there. “Unrelieved and cultureless banality,” “never was dialogue more inept; to imagine it spoken is impossible”; as a novelist he “doesn’t exist; he doesn’t begin to exist.” He went on: Snow understood nothing of the humanist establishment he claimed to represent; his “culture” was the empty, shallow culture of the Sunday papers—cocktail-party stuff, worlds away from the real culture that is charged with taking art seriously, with cultivating it and preserving it for the future.

So that nobody might imagine he regarded Snow as anything like a colleague—to avoid “normalizing” him, if you like—Leavis dispensed with every speck of politeness. Snow’s literary culture, he said, “is something that those genuinely interested in literature can only regard with contempt and resolute hostility… his ‘literary intellectual’ is the enemy of art and life.”

This rhetorical firebomb had a blast radius so deep and wide that you can still feel the heat all the way from the 21st century. But Leavis’s real target wasn’t C.P. Snow at all. His real enemy was the far more dangerous one he’d long fought as a critic and teacher: The machine-world of bloodless materialism he saw smashing down on human freedom. For Leavis, Snow was only the Man’s messenger, fit to be shot.

It is the world in which […] ‘standard of living’ is an ultimate criterion, its raising an ultimate aim, a matter of wages and salaries and what you can buy with them […] and the technological resources that make your increasing leisure worth having; so that productivity—the supremely important thing—must be kept on the rise, at whatever cost.

The capacity for art, the literary capacity to make and interpret meaning was in danger from this encroaching materialism and the passivity it would produce, so that life’s real values—the humanistic values of creativity, beauty, communication, aliveness—would slip away, leaving only a dry, empty ‘prosperity’ in their place. Snow’s “terrifying confidence of simplification” made him not only an inferior novelist, not only an inferior technologist and scientist, but an inferior human being, lacking imagination or humility enough even to speak cogently on the subject of what was really about to come down.

And how right Leavis proved! (Except, alas, for the “increasing leisure” part.) Technological progress really did become “the supremely important thing” for the next half century. Now we can see who came closer to the mark about what would happen next.

In the event, the vain, blindly stampeding version of “science” that Snow championed unleashed an avalanche of unforeseen disasters. Yes, there were magnificent triumphs: There is less hunger in the world and there are better infant survival rates, there is stem cell therapy, and immunotherapy, and a cure for Hepatitis C and all the mindblowing miracles of the information age that make it child’s play to read almost anything, and communicate with people nearly anywhere, almost instantly.

Also instability and violence on a global scale, a vile, repulsive herd of international plutocrats who’ve got the world by the throat, a dangerous imbecile and freak in the White House and a nonzero chance that we’ve poisoned the whole planet, all as the result of our addiction to Progress. As for the world’s poor, they are still with us, in their hundreds of millions. There are children still dying of politically engendered starvation, or dying of cholera, or drowning and washing up dead on a Turkish beach.

Scientific progress, it turns out, isn’t the magically self-correcting engine of eternal benefits that the 20th century Snovians, drunk on Progress, had blithely assumed it would be, and the 21st century is only barely now waking up to the horrible hangover.

Leavis, for all his irascibility and dogmatism, foresaw this danger clearly in 1962.

The advance of science and technology means a human future of change so rapid, of tests and challenges so unprecedented, of decisions and possible non-decisions so momentous and insidious in their consequences, that mankind—this is surely clear—will need to be in full intelligent possession of its full humanity […] What we need, and shall continue to need not less, is […] an intelligence, a power—rooted, strong in experience, and supremely human—of creative response to the new challenges of time; something that is alien to either of Snow’s cultures.

Leavis was right, but that doesn’t mean he won the argument. He didn’t. Form beat substance completely among the squares, who lost no time in taking him to task for having been rude. “Dr. Leavis only attacked Charles because he is famous and writes good English,” said Dame Edith Sitwell, who wouldn’t know good English if it whacked her with a bowling ball. Lionel Trilling called Leavis’s tone “impermissible,” and Lord Boothby was all on about his “reptilian venom.” Snow had a lot of friends and colleagues in high places… or put it this way, Leavis was not on visiting terms with Edith Sitwell. Though it should be noted, too, that Leavis had some public champions, and no small number of his Cambridge colleagues, better people, smarter people, congratulated him in private for having had, as the retired Canon Professor Raven put it, “the courage to say what some of us ought to have said long ago.”

All this happened because, with science become almost a religion, with the gradual deprecation of the values pertaining to art and to literature and philosophy, everything is, must be, all about getting More. Put Progress in charge, belittle humanist principles, and what you’re going to get is a whole lot of counting. In other words: if More is the only good thing left, More is not only better, it’s all there is. There’s nothing else.

Leavis was keenly alive to the “callously ugly insensitiveness” and the deeper significance of judging the quality of life this way. He railed against “the world in which the vital inspiration, the creative drive, is ‘Jam tomorrow’ (if you haven’t any today) or (if you have it today) ‘More jam tomorrow.'”

Jam—for which, today, we may read iPhones, Amazon Prime Day, summering at the beach, wealth-worshipping Hollywood comic book movies starring Robert Downey, Jr., complicated devices for making the purest coffee, flying first class in ever-larger airplanes, food so elaborately wrought as to be entirely unrecognizable—has been the “vital inspiration, the creative drive” of Western culture for a half century. Leavis, who in 1962 couldn’t possibly have imagined the degree to which he would be proved right, described the coming cultural revolution as “the vision of our imminent tomorrow in today’s America: the energy, the triumphant technology, the high standard of living and the life-impoverishment—the human emptiness; emptiness and boredom and craving alcohol—of one kind or another.”

In a world where nothing matters but More, numbers are evidence; numbers are proof. Net Worth. GDP. Polls. Bank balances. Probability values. SAT scores and college rankings. Yelp ratings. Stock charts and company valuations. It’s Science!

Without a number, your thesis is necessarily subjective, speculative, pointless, “just your opinion, man.” Numbers are truth. Numbers are meaning. Voilà the sole commandment of the God of Progress, Thou Shalt Measure. We’ve reached a worldview in which nothing is really “true” in the absence of a number. How else to measure Progress?

The Two Cultures debate is a particularly clear expression of this, the key conflict of the 20th century, as we’ll be exploring in this occasional column. William Morris fought the same kind of blind, materialist industrial “progress.” The Bauhaus (and later, Dieter Rams at Braun) set craftsmanship up against “fine art” in a similar tension against the machine world. Pioneering epidemiologist Roy Laver Swank struggled likewise against a hidebound medical establishment from 1952 onward. Karl Popper had a parallel conflict with Thomas Kuhn in the field of scientific philosophy in 1965; Renata Adler had a literary version of it with Pauline Kael in 1980. Mark Zuckerberg patiently explains how Facebook can manage media and society via algorithm. Technical, expert, bureaucratic, scientific, commercial triumphalism against the human, the mercurial, the personal and imaginative. Digital vs. analog. The fixed idea versus the fluid one. The seeking of wealth versus the expansion of imagination. The virtues of push, calculation and certainty, against those of provisionality, experiment and skepticism.

Humanistic values have long been on the losing side of this battle. The magic wrought by science and technology, together with the arrogance it brought its leaders, skewed our culture more and more toward the “pragmatic” Snovian view: that scientists have a better grasp of the truth than the sloppy practitioners of the sissified arts of literature, history and philosophy, with the results that you see all around you.