Edna Lewis knew what it was like to be poor. She was born in 1916 in Freetown, Virginia, a town formed by a group of newly emancipated former slaves, one of whom was Lewis’s grandfather. Flush with farmland, Freetown was a small community, and tight-knit as a result.

When Lewis lived there as a child, everyone, even the kids, worked hard. But they learned to find pleasure in their labor, because its fruits gave them sweet relief: wild strawberries, walnuts, persimmons.

“Whenever there were major tasks on the farm, work that had to be accomplished quickly (and timing is so important in farming), then everyone pitched in, not just family but neighbors as well,” she wrote in her second cookbook, 1976’s The Taste of Country Cooking, arguably the most famous of the four cookbooks she published throughout her lifetime. “And afterward we would all take part in the celebrations, sharing the rewards that follow hard labor.”

This way of life was cut short in 1928, when her father died. Her mother, who would die when Lewis was 18, just couldn’t take care of her and her seven siblings, so Lewis traveled north once she turned 16 in 1932. Her first stop after Freetown was Washington, DC, where she stayed with family. In the 1940s, she boarded a bus to New York.

This is where the biography of Lewis, who died in 2006, gets a bit spotty. Most retellings of her life breeze past the next decade and a half, focusing on her pastoral and idyllic childhood before the frequency drops around the 1930s and 1940s. She found success working as a seamstress during that time, with clients including Marilyn Monroe. But the thread picks back up in 1948, when she joined Café Nicholson as its only chef. There, in that upscale restaurant on East 57th Street in Manhattan, she was a rare Black woman chef in a New York restaurant frequented by white patrons as famed as Tennessee Williams and Eleanor Roosevelt. Her food was, by all accounts, exquisite, with a menu that rotated around her lingonberry pancakes and bitter chocolate soufflés.

But there is one name that pops up in the retellings of Lewis’s years before Café Nicholson: that of her husband, Steve Kingston. He was a former merchant marine whose politics tilted left. He was a communist.

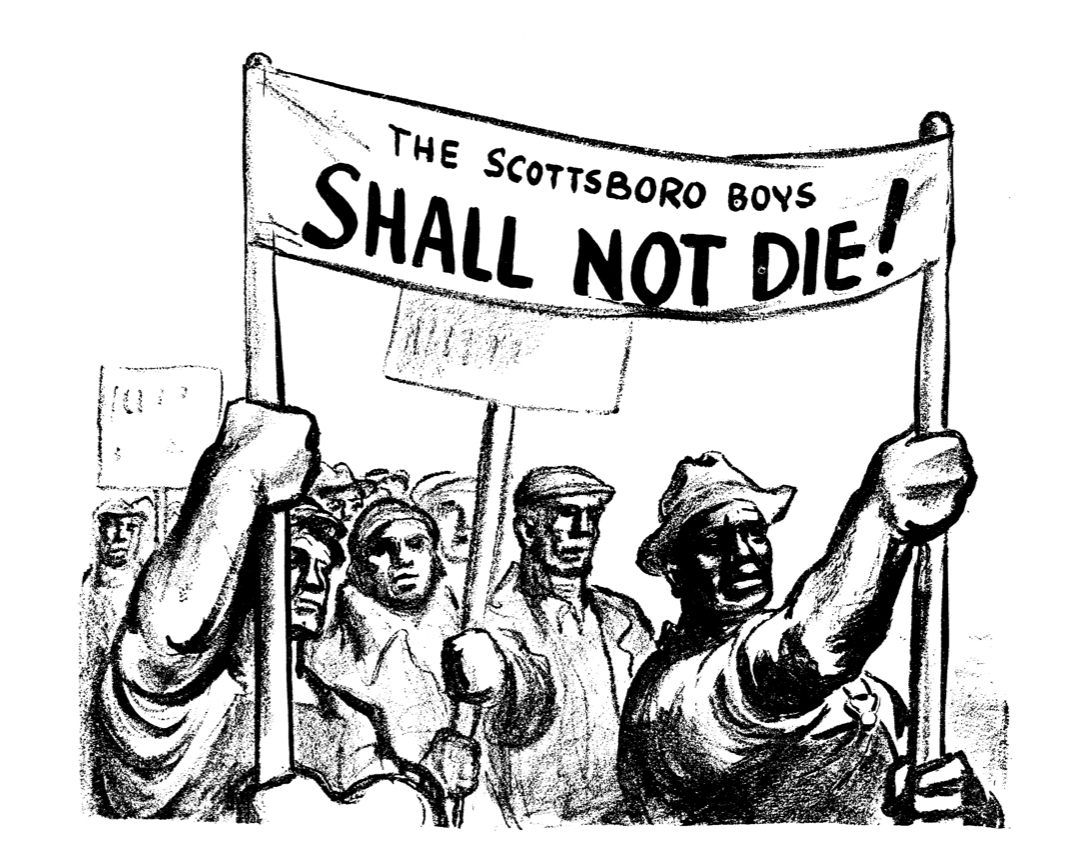

Kingston is effectively a ghost in Lewis’s biography. Lewis rarely spoke of him on the record, one of the few instances being a 2001 interview with novelist Chang-Rae Lee in the now-defunct Gourmet, one of the final interviews she gave before her death in 2006. Lewis explained that Kingston spent his days campaigning fiercely on behalf of the Scottsboro Boys, marching and rallying for the eight Black teenagers falsely accused of (and later prosecuted for) raping two white women on a freight train traveling through Tennessee. Lewis wouldn’t attend these rallies herself, she explained to Lee, but she did her part: when he and fellow activists gathered in the apartments of friends, she would cook for them.

“He was a Communist,” Lewis told Lee of Kingston. “We all were.”

“Are you still?” Lee asked.

“I suppose so,” she responded, smiling. “Yes.”

Though Lewis died in 2006, there’s been a welcome renewal in interest in her work over the past few years. This push began with her inclusion in the United States Postal Service’s line of Celebrity Chefs Forever stamps in 2014, alongside considerably better-known white American luminaries like James Beard and Julia Child. (Perhaps the conferral of celebrity status was wishful thinking, steeped in guilt: in January 2017, an alarming number of Top Chef contestants confessed they didn’t even know Lewis’s name.)

I came to Lewis’s work in October 2015, when the New York Times Magazine devoted its cover story to her in its annual “Food Issue,” asking whether she had really gotten her due in today’s era. Though she never became a household name, the local and seasonal sensibilities she championed early on have now become de rigueur in food circles. I have been hooked on her work ever since.

With time, certain aspects of Lewis’s legacy have come into clearer focus. She wrote of what is now recognized as a farm-to-table consciousness when most Americans might have regarded it as radical, fringe thinking. She was the rare Black, Southern female voice who broke through to an audience of white readers who might have been predisposed to thumb their noses at the notion of Southern food and the images it connoted of a backwards people.

But there is still a gauzy layer that separates us from the real Lewis, as if her image has softened in death. As my own understanding of Lewis’s work has moved from ignorance to appreciation, her politics have always struck me as the void at the center of a woman who is otherwise well known. She has been written about extensively, after all, so much so that food historian Sara B. Franklin corralled some of Lewis’s friends and admirers to contribute to a book of essays devoted entirely to Lewis last year. But the question of Lewis’s politics linger in that book, Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original, too. As Franklin explained in an interview with her publisher, the University of North Carolina Press, the book represents an attempt to “look beyond the hackneyed, saccharine narrative that gets passed around about [Lewis].” But it contains few mentions of Lewis’s communism; any instances in which her politics are talked about treat them as a mystery.

I’m tempted to wonder whether the fact that Lewis’s communism so rarely gets discussed has to do with the antiseptic image she has been saddled with in death. The image of Lewis as a communist, and all it implies, may jar with the more acceptable one of Lewis as dignified and regal, the “Grand Dame of Southern cooking.”

But the more mundane reason for this oversight is that archival information on the communist period of Lewis’s life is maddeningly difficult to come by, and she usually withheld information about it, too. The aforementioned Gourmet interview was one of the rare cases where she did speak about it. Another occasion came four years later, in a 2005 documentary, Fried Chicken and Sweet Potato Pie, directed by independent filmmaker Bailey Baras and derived from exclusive interviews with Lewis. The film walks through Lewis’s early years in New York and the sense of alienation she felt as a Black woman up north. She found allies in the Communist Party USA.

“They were the only ones encouraging the Blacks to be aggressive and to participate,” she said. “They gave me a job typing.”

Her job was typing for the Daily Worker, a paper run by the Communist Party. “It was a nice group of young people,” she said. “We used to cook for each other on weekends. I was the only one cooking Southern food. It was at these parties where I started to get my reputation for Southern cooking.”

Through these activities, Lewis met a photographer named Karl Bissinger and an antiques dealer named John Nicholson, the two men who would later open Café Nicholson. “It was a natural, particularly for people who understood what it was like to be poor, who had come from working-class families, who understood the division of spoils in this capitalist country was unfair,” Bissinger, also an acknowledged member of the party, explains in the documentary. “And one wanted very much to change into some sort of socialist kind of government. The nearest we had to that point was the Communist Party.”

In a phone call, Barash told me she worked on the documentary for the better part of two years, examining Lewis’s writing closely and speaking to friends. Throughout this process, though, the subject of politics rarely came up, and no sources volunteered information about it.

“There were certain things she didn’t write about, and one was her marriage,” Barash told me. “I didn’t even know she’d been married when I made my documentary.”

As a result, the name Steve Kingston doesn’t appear once in the documentary. Beyond the film, there’s a dearth of information about Kingston, particularly as he relates to Lewis. Historian Mark Naison’s 1983 book, Communists in Harlem During the Depression, describes a Steve Kingston who was “a gruff, powerfully built ex-Garveyite.” Marcus Garvey was the Jamaican man who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association, or UNIA, which had an adversarial relationship with the Communist Party in those days.

What Barash knows for certain is that Kingston disapproved strongly of his wife’s involvement in Café Nicholson. Lewis left the restaurant in 1954, reportedly at his urging, after he grew frustrated with the fact that she was consistently serving people who represented New York’s most irritating bourgeois excesses.

“He used to always say, ‘This restaurant should be for ordinary people on the street. You’re catering to capitalists,’ ” Nicholson, who died in 2016, told the New York Times in 2004. “It was such a bore.”

Little is known about what Kingston and Lewis did in the years between 1954 and 1972, apart from the couple reportedly having an unsuccessful stint maintaining a pheasant farm in New Jersey. But Lewis became a widow in the 1970s. According to Lewis’s cookbook editor, the late Judith Jones, Kingston died in the midst of Lewis writing her first cookbook, 1972’s The Edna Lewis Cookbook.

Tonally, The Edna Lewis Cookbook is a universe away from The Taste of Country Cooking,which she wrote four years later. The Edna Lewis Cookbook, which replicated many of the dishes she cooked at Café Nicholson,has its merits as a cookbook, but as a piece of literature, it comes across as spiritless when read alongside The Taste of Country Cooking.

Jones, the Knopf editor responsible for taking a chance on now-established culinary voices like Julia Child and Madhur Jaffrey when no other editor would, was bewitched by the clarity of Lewis’s memory when she first met her in 1972. Jones certainly didn’t think that The Edna Lewis Cookbook sounded much like the Lewis she knew, but Lewis’s memories of her childhood rang clear when Jones asked her to recount them. According to Jones’s memoir The Tenth Muse, they decided to work on a cookbook based on “the ways in which the people of Freetown raised their food and prepared it throughout the year.” But Lewis turned in a first draft that Jones felt had failed to capture her spirit. At this point, Lewis’s cowriter, a socialite named Evangeline Peterson who had cowritten her first book, ceded full control over the writing to Lewis.

Finally, Lewis’s voice emerged. She wrote of her memories of the Freetown she left behind and her desire to recover those memories through her cooking. She structured the book around the seasons, with sensory vignettes that re-create the memory of each, from the “moist smell” of chickens hatching in the spring, cooing as they emerged from their eggs, to the image of her slurping a turtle soup in the summer. Throughout the book, there are vivid images of people driven by a communal spirit, people trading seeds and setting hens, schoolkids helping Lewis’s mother shuck corn once fall hit.

“Her communism is fairly muted in her writing,” Franklin, the editor of Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original, wrote me via email. “What you get from her is a very clear sense that she believed in enoughness, in doing things on a human scale, on looking the painful parts of our history and lives straight in the eye and confronting them, and in dignity for all.”

In his essay for Franklin’s book, food scholar and former chef Scott Alves Barton draws a distinction between Lewis’s writing and that of a Black, Southern female contemporary, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor. In her 1970 cookbook, Vibration Cooking: or, the Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl, Smart-Grosvenor rolls her eyes at white tastemakers like Julia Child and James Beard, singeing the white food establishment and all it stood for. Barton characterizes Lewis’s voice as “measured and assured,” Smart-Grosvenor’s as “improvisatory and strident.” In a phone conversation with me, he defined Lewis’s expression of her politics as “an embodied practice, a quiet fire.”

“She was very quiet, but not shy,” Barton told me. “She didn’t have to shout. She just did it.”

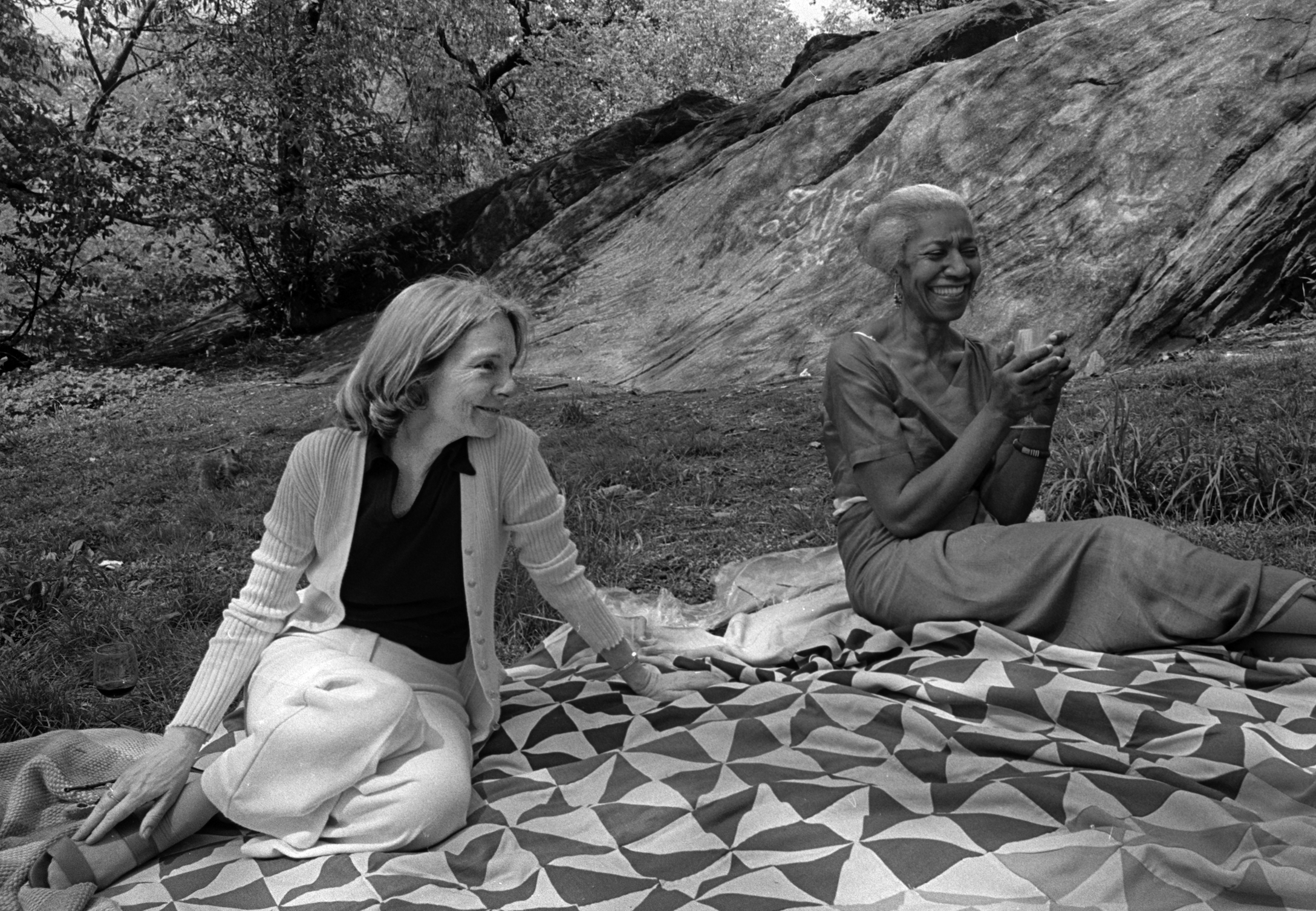

“I’d envisioned a chef of Lewis’s stature spending her late-in-life years in something closer to prosperous—a big, rambling house, maybe, with a huge country kitchen outfitted with butcher-block counters and a deep soapstone sink,” Chang Rae-Lee wrote of Lewis in Gourmet. “Or perhaps something in the polished-brass mode of the New South, but still grand and stately.” That was not the case. Instead, he noted, Lewis lived with her caretaker, white Southern chef Scott Peacock, “in a patch of low-rise, older brick apartments,” so unremarkable that Lee compared it to a tiny college dorm.

The great paradox of Lewis, Franklin reminded me, is that she died childless and without much money, never achieving the kind of wealth of the people she cooked for at Café Nicholson—and certainly not the kind of riches one may associate with a celebrity chef. Franklin suggested you could see Lewis’s fate as an oblique realization of her a refusal to bend to the rigid rules of capitalism. By that same token, you could also view it as a defeat.

“This is, to be clear, not me saying she was a failure, but if you look at the way we measure success in this country, she didn’t check the boxes,” Franklin said. If Lewis failed to flourish within capitalism’s marketplace of meritocracy, that lack of success was abetted by factors beyond her control, her race and Southern roots. She belonged to a generation that experienced firsthand the failure of a larger communist project, one that was unable to implement lasting political change.

If Lewis’s communism shows up in her writing, Franklin said, it comes in whispers, in the vision of the world she offers. This is how Franklin understands the idea of “enoughness.” She told me that Lewis’s politics and her way of making food converge here, in the principle of “equal distribution, with the notion that everyone will contribute in order that everyone will have what they need, and no more.”

Perhaps it’s possible to read The Taste of Country Cooking as a communist text by these same parameters. You don’t have to stray far from Lewis’s words to see her politics, which emerge in the images of communal living she wrote of in The Taste of Country Cooking. She conjures a vision of a world like Freetown, where power differentials between groups barely exist, to the point that there is barely a distinction between children and adults. In her own childhood, the adults in Freetown “showed such love and affection for us as children, at the same time asking something of us, and they knew how to help each other so that the land would thrive for all.”

James Beard famously read Lewis’s prose in The Taste of Country Cooking as a call to action. “Edna Lewis makes me want to go right into the kitchen and start cooking,” he said of the book. But this motivation is not just born of hunger, though Lewis could write the hell out of a recipe. Lewis makes us want to cook because she marries each recipe to a way of life that seems impossible to realize in consumer society. The memory of Freetown never left her, but the way she wrote about it is aspirational, as if she’d been writing of a place that was lost.

Maybe that’s where her politics have been hiding all along, nudged between recipes for dandelion blossom wine and cold roast pheasant. “The spirit of pride in community and of cooperation in the work of farming is what made Freetown a very wonderful place to grow up in,” she wrote in The Taste of Country Cooking. I’ve returned to these words often, seeing a vision of Lewis’s politics more clearly than ever: The Freetown she describes is a hamlet, a community living outside the disturbance of capitalism’s demands. Writing was her attempt to summon that paradise again, a place like Freetown where everyone worked and fed one another.

I now read The Taste of Country Cooking as a plea to convince us that cooking could level us across social strata as it did for her in Freetown, where such distinctions didn’t apply. Does this make The Taste of Country Cooking, and the woman who wrote it, communist? To borrow Lewis’s own words, I suppose it does.