September 14, 2018

Berkeley, CA

It was almost seven a.m. when Steve woke me from the dense, dreamless sleep of someone who chewed the second half of an Ambien at one a.m. I try to be sparing with Ambien, not because I have puritanical feelings about sleep medication but because when I take it I wake up feeling like I’ve been dead for a month.

In the kitchen, Jane, in an Elsa nightgown that’s looked tawdry since its “itchy” sleeves were hacked off, sat in the middle of a heap of bubble wrap, old newspaper, and labels. Jane was working a pair of scissors the length of her forearm. I put out my hand to take them from her but stopped myself. I asked if she wanted oatmeal. “No,” she said, shaking her head impatiently, “I’m working on my robot.”

I stepped over her “robot,” poured coffee, and put a pot of oats on the stove. Since it was field day, I decided to make two sandwiches, one for Jane and one for me. Henry buys lunch at the cafeteria now that he’s in kindergarten, thank god, and Steve packs leftovers, I guess, or buys something, I don’t know, and I usually throw into my work bag whatever requires absolutely zero effort. A thing of yogurt. The rest of the salami. An apple. I hate lunch-making so much I would rather eat garbage off my classroom floor than take one extra minute to prepare a sandwich for myself, but today was field day.

I put the bread on a plate and divvied up the last of the sliced turkey. Henry entered. He is into rotting things, so I showed him the two halves of the avocado I cut. “Doesn’t it look like the curse of Te Ka?” I said. Henry said, “Aaaaaah, I already know that,” in the exact cadence of a teenager trying to stop his mother from saying “condom.” He came in for a hug and then tackled Steve, who was making Henry’s usual, a peanut butter, jelly, and honey sandwich. I sliced a second, much better avocado and went to get the mustard from the fridge when I heard Jane call from the bathroom with words that flooded me with dread: “MOM, I AM READY TO BE WIPED.” I left the sandwiches half made. Jane, naked, in downward dog on the bathmat, was indeed ready to be wiped.

In the kitchen, the oatmeal was burning and Steve was wrapping things in foil. On weekday mornings, our marriage runs like a tightly choreographed ballet, if ballets consisted of dancers doing extremely boring things while looking increasingly annoyed at each other. I put the scissors up high and ate what was salvageable of the oatmeal, then hustled Henry into clothes while Janed argued with Steve about the time. “But it is only eleven-forty,” said Jane, whose understanding of the argument’s formal qualities has eclipsed her grasp of time. “It is too early. It’s only forty-nine o’clock.”

Last night, I had told myself that I would leave early to buy celery and lettuce for students to feed the animals at field day, but I now knew that was a lie. I rifled through the place where all my self-delusions go to die, the vegetable drawer of the refrigerator. There were some wrinkled peppers deflating sadly like old balloons, sprouted potatoes, a fossilized green onion that had become one with the bin, but no celery or lettuce. On a high shelf was a bag of fresh-looking, dark green arugula. I stared at it with the fridge door open for at least thirty seconds, wondering if arugula was a kind of lettuce and whether this particular mental decrepitude was a side effect of Ambien. It seemed like lettuce? I shoved it in my bag, kissed Steve, and said goodbye in an elaborate, multi-step ritual for each child.

I used to have a long commute, over the Richmond bridge, but I recently changed jobs to work closer to home. When I used to drive for like an hour, actively murdering the environment every day, I never felt bad about it because I couldn’t think of a way I could not. Now that my drive is like four minutes, tops, I feel as though I’m going down the block crushing Styrofoam in my bare hands and scattering it like birdseed. I parked right at the edge of a red zone, maybe in it, and called out to a student for a second opinion. She’s in my one eighth-grade class, and last week she yelled, “That’s bullshit!” when I asked her to spit out her gum, which may not sound like much of a recommendation, but it is. She cocked her head to the side and made a judgment quickly. “You’re good, Ms. Petrone,” she said, and I believed her.

It was zero period when I arrived. The campus felt sleepy, overachievers tucked into their electives and only a few students hanging out by the gate. I slipped my green AC Transit lanyard around my neck. It’s not actually my lanyard; it came attached to the key when I picked it up in August, grimy from the neck of whoever wore it last. I meant to replace it, but I spent a bunch of money buying pencils and paper and hand soap, and no one will hold my eye contact when I say “reimbursement,” so grimy lanyard it is. Like a lot of public-school shabbiness, the green AC Transit lanyard becomes functionally invisible, then I’ll suddenly see it and feel bummed out.

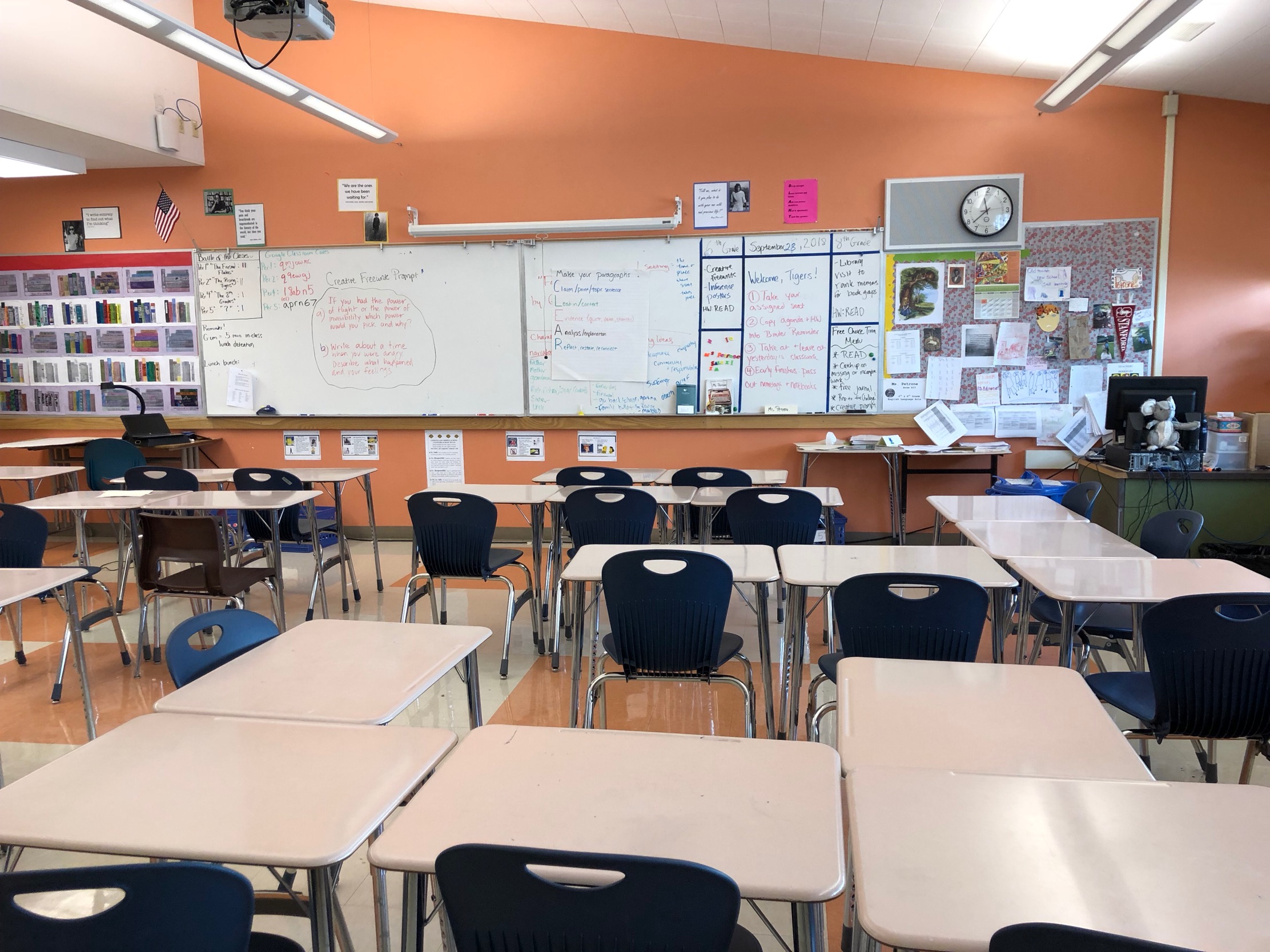

School routines, the repetitions, the bells that make me feel like a hamster sometimes are comforting, and always do strange things to my sense of time. At 8:45 a.m. the bell rings. Students were giddy today with the lightness of carrying only their lunches. When I told them to take out their learning logs, six or seven hands immediately flew up to remind me that I had said not to bring books for field day, which was true. “That’s okay,” I said, coming up with a plan as I talked. I weaved among the desks to give assistance; kids who did not require it used their voices and hands to pull me towards them; the ones who needed everything tried to camouflage. One boy disappeared his blank page in his backpack. “It’s done,” he said, like he’d killed it. “Show me,” I said. I smoothed out the crumpled ball he produced.

At 10 a.m., the school buses swept us up the steep hill, past the mansions on the way to Tilden Park. We were let out by a field. A pretty fundamental feature of my personality is that I never feel more alienated than during “community building.” I am seized with visceral horror recalling the memory of standing in a circle in seventh grade drama as an invisible ball was tossed around. If it was “thrown” to you, you had to “catch” it while introducing yourself and saying what activity you liked to do that began with the same letter as your name. I’m Joanna and I like to … jump? eat jellybeans? What humiliating thing was going to come flying out of my mouth? I still do not like improv, balls, or touching. As a teacher, though, I try to model a “growth mindset” for my students. I passed out Nilla wafers, and kids stuck them on their foreheads; the first one to get the cookie in their mouth without using their hands won. Except for the kid who took a crumb to the eye, everyone had a good time. Then it was time for Little Farm.

Joanna Petrone

Joanna PetroneMany signs said only celery and lettuce, and one signed warned that bunnies’ GI tracts are so delicate they can die from indigestion, but no signs mentioned arugula, specifically. I think to teach middle school, you have to make peace with the fact that no matter how good you are at teaching there will be some percentage of students who remember you only for the psychic scars you’ve inflicted in spite of yourself, by accident. On my first day as a teacher, I pulled a girl aside on her way to assembly because she had bled through the seat of her pants. Today, I decided to err on the side of caution. No feeding, I said. Some growing pains are unavoidable, but I was proud no child killed a bunny by accident this field day.

We returned to the field. Up by the bathrooms, a group of girls sat on the picnic tables, passing around cherry ChapStick and secrets. A group of boys ran around hitting each other. A dog showed up and was perfect, chasing balls, letting kids walk it on a leash. I noticed one of my students on her own for a long time, examining the moss on trees, or pretending to. I asked a couple of girls to invite her to their blanket. They did. Then tag broke out, and she was alone.

At 1:45 p.m., we crammed back on the buses. A girl talked to me about her hobbies: aerial dancing, writing poems, “the radio.” This is one of the differences I notice between sixth graders and eighth graders: sixth-grade girls are so buoyant. With eighth graders, when you ask the students to write a reflection on their work, girls who had knocked themselves out writing elegant, clear, original pieces would say that they had tried their best and though it wasn’t very good, they hoped I would would give them a B+, please. I stopped doing this exercise because it depressed me.

Once home, I was too tired to do anything besides lie on the couch and let the kids watch cartoons. Years ago, we would have starved to death without the freezer aisle at Trader Joe’s, but it’s spaghetti tonight. After, we walked to the park. I sat on a bench and rested my head on Steve’s shoulder. Henry and Jane were already gone, merged with the horde. The park was busy, kids jumping off the spiral slide, centimeters from bashing their heads, but it felt calm to me because I was not responsible for any of them. Well, only two.

I spotted one of my students, the girl who had been hanging out with the mossy trees. She was on a swing now with her back to me, next to a girl I didn’t recognize. I thought about saying hello to my student, but she looked so free. The golden hour was stretching to a close; parents in work clothes hesitated to round up their kids. The two girls pumped their swings higher and higher, the full force of their bodies pulling back on the chains which swung so high they slackened as they peaked. The sun sank lower, and Steve started looking for our kids’ shoes. The sky was a wild and fiery orange as we left; the two girls were still there, swinging as high as they could, legs kicking out, powerful and dark against it.

Joanna Petrone