La Comédie humaine is the diary of American expatriate Claire Berlinski’s amazing journey onto the Parisian stage. (Names have been changed to protect privacy.) If you missed the Introduction, we urge you to begin there.

The audition, she explained, was simple. I was to show up for two classes spéciales and just … participate. There would be “exercises,” she said, and “improvisation.”

When, I asked?

She looked down at her clipboard and flipped through a complicated series of schedules with many crossed-out names. “Ah! You’re lucky. You could start the trial tomorrow at 19:00! You’ll be with Fabien.” By coincidence, I’d approached her on exactly the right day.

I thanked her lavishly, realizing I was now in too deep to get out, walked home, and calculated that I had eighteen hours to prepare.

I Googled “How to act.”

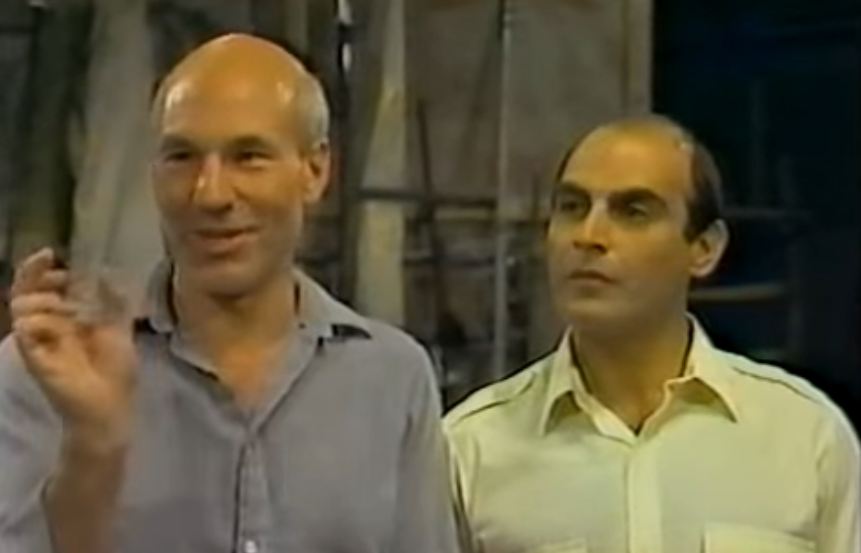

Wikihow told me that if I knew what motivated my character, everything would fall into place. I did a brief seminar with Roger Allam—better known to you, probably, as Inspector Javert—who recommended I put on “magnificent, large-scale plays in Dorset that involved the whole community.” I immersed myself the Stanislavski System, then took a few lessons with Lee Strasberg and Sanford Meisner. I learned from them all and I won’t forget to thank them when I thank the Academy, but ultimately, I put my confidence in this video. I liked it because I could follow the advice with only the household items I had on hand.

You just need observation skills, a mirror, emotional range, communication skills, confidence, and a friend or family member, it said. Mirror: check. The rest: subjective.

For “a friend or family member,” I thought I’d call my brother Mischa and my nine-year-old nephew, Leo. They were, after all, the ones who’d put the idea of acting in my head. In fact, when last they’d visited, we’d spent a whole morning working out how we’d stage an avant-garde version of Hamlet starring my seven cats. Leo would be Catlet’s casting director, metteur-en-scène, and videographer. I’d be the wardrobe director. Süleyman would be Hamlet, and Daisy would be Ophelia.

We had it all figured out, but then Mischa declared we were doing everything wrong and insisted we watch John Barton’s nine-part miniseries, Playing Shakespeare. Hamlet and the rest of the cast fell asleep, and after the third episode, Leo, who had seen the series before, declared he was sooo bored. He’d been a good kid all morning despite being stuck in a small apartment that smelled bad with Weird Aunt Claire and the cast, so we abandoned Catlet and went to the Paris plage.

But as we walked toward the Seine, we invented the King John game:

The rules were that you had to do it the way David Suchet and Patrick Stewart do: a quick, seamless round, picking up exactly where the last speaker left off, without any pauses. Since there were three of us, we each took turns starting, like so:

KING JOHN (Mischa): Death.

HUBERT (Claire): My lord?

KING JOHN (Leo): A grave.

HUBERT (Claire): He shall not live.

KING JOHN (Mischa): Enough.

Stop right here, grab anyone in near proximity, and give it a try. Seriously. I’ll wait. The rules: You have to remember those five lines. It’s only ten words, so it shouldn’t be hard. You have to say them in the right order. And you have to do it one single, seamless verse without any pauses, like David Suchet and Patrick Stewart do, as if you’re just one person speaking. Give it a try.

How’d that go?

Yeah, I thought so. You’ve now grasped why David Suchet and Patrick Stewart are legendary Shakespearean actors and you’re not. Don’t feel bad. We couldn’t do it right either—not even once.

When I woke up I decided to read about auditions, instead, looking for advice about how to get in the right frame of mind.

I wished my mom were still alive. She knew all about auditions. I thought about all the questions I wished I’d asked her when I still had a chance. I remembered her carefully ironing stacks of handkerchiefs before her concerts, when I was a little kid. Why did she do that, I wondered? Was she worried her nose would run on stage? She must have been. But why handkerchiefs and not tissues? I thought about her voice and imagined what she would have said. “Handkerchiefs look nicer.”

I remembered I that I had a white linen handkerchief, one with intricate geometric patterns hand-embroidered in royal blue silk. In fact, I’d bought it as a gift for my mother while I was on a press junket in Morocco. The seamstress proudly showed me that it looked exactly the same on either side. It was a special Moroccan stitch that left no knots or tangles. I just looked at the elderly women in the shop, bent over their looms and their needlework, and thought, “Dear God. The last thing I want is a hand-embroidered Moroccan tablecloth. But I just can’t leave without buying anything.” I remembered my mom’s penchant for handkerchiefs and decided buying one would be a good compromise—light enough not to weigh down my luggage, not too expensive. But when I next saw my mother she was, to my surprise, dying. I gave her the handkerchief. She smiled and told me it was beautiful. Then she died. So I brought it back to Paris with me.

I put it in my handbag. If they wanted to see if I could weep on command, that would be a total tearjerker.

Next I consulted Wendy Alane, the Hollywood Talent Manager. Wendy’s advice: Never shake hands, because that particularly annoys casting directors. Don’t make small talk. Don’t mention your personal life, and above all, don’t complain about what happened to you that day. The casting director wants to know you’re a professional.

My mother would have endorsed that advice, if not Wendy Alane’s hair colorist. She got through the last weeks of her career (and her life) without once complaining that she was dying of pancreatic cancer. In fact, she didn’t even mention it. And astonishingly, no one noticed it. I’ve never known what to make of that. The show must go on—and so it did.

Wendy Alane stressed the importance of arriving at least fifteen minutes early so I wouldn’t convey a stressed-out vibe. She warned me not to talk to the other actors, who would be trying to psych me out and fill me with negativity.

I practiced it all in front of the mirror—arriving early, shunning the other actors, and conveying my professionalism. I shunned the other actors in front of the mirror a few more times, and put on my favorite bright-red lipstick.

I was as ready as I’d ever be, I figured. I counted the cats (I always do that before I leave) and walked out the door.

I arrived exactly fifteen minutes early, braced to ignore a horde of competitive Parisian actors all trying to psych me out. But the street was empty, the door was closed, and when I pressed on it, it didn’t open. Unsure what to do, I checked my phone (exactly 18:45), rustled through my handbag, re-applied my lipstick, and checked my phone again, managing somehow to get both nicotine gum and lipstick on my mom’s handkerchief.

At 18:58, I was still alone on the street, and began to suspect I’d somehow managed to get the time wrong.

“Bonjour!” said a faceless local, startling me. “T’es venue pour la classe?” He produced a key from his briefcase and began unlocking the door.

Had he really just tutoied me? I was taken aback, but recovered fast. “Oui!” I replied professionally.

“Fabien,” he said, offering me his hand to shake.

He pushed aside the velvet curtains and waved me into the empty theater. “You’re a bit early,” he said. “Have a seat.”

Claire Berlinski